Dislaimer: I am not a food science guy and I have no formal training in dairy science. However, I worked in a dairy processing plant as a lab tech for three years and picked up a few things. This is my perspective from the manufacturing side.

Having worked in a dairy processing plant, I learned that there is no mystery to how cheese was invented/discovered. Just let milk sit unrefrigerated for a few days and it will clabber up. Stray bacteria, yeasts and mold spores are in the air and breath everywhere and many, if not most, are capable of feeding on the milk. In doing so, acids may be produced which will denature and unravel the proteins and bring them out of solution as a solid. Many microorganisms can ferment milk, but that is not to say that the cheese will be desirable or even edible. Before refrigeration, cheese was inevitable. Even with refrigeration cheese will happen, only a bit slower. Be one with the cheese.

As an undergraduate, lo these many years ago, I spent a few years working in the QC lab of a diary processing plant. My job was to perform certain analytical and microbial quality control procedures on the many products the plant manufactured. We produced fluid milk, cottage cheese, sour cream, whipping cream, half-and-half, single serving dairy creamers, a flavored shake product, orange juice, and flavored novelty beverages for kids. We packaged under our brand as well as for other brands.

People are very particular about their milk. Chunky milk sets off alarm bells for most of us. Many people dump their milk at the expiration date. Unless the milk has been allowed to warm up to room temperature or it has been contaminated, it should be good for another week. The expiration date is when the producer’s guarantee of freshness expires, not when it will go bad. Encountering pathogens in milk is comparatively rare these days.

The input of milk to the plant was in the form of raw milk straight from the farms by way of shiny stainless steel tanker trucks. We would receive 2-3 6000 gallon tankers per day. If we rejected a tanker, there always seemed to be another plant nearby that would take it. Rejections, which were few, were usually due to off-flavors picked up from the farm or it was high in coliforms.

Before the milk was unloaded it had to be tested. First, the receiving operator would insert an agitator into the tanker manway and stir the raw milk to mix the cream back into the milk. He would then use a stainless steel dipper and pull out a sample for the first tests. The temperature of the tank load would be taken, then the sample would be thermostatted to a specified temperature. At this point he would take a mouth full and approve it for taste and odor. This is called an organoleptic, or taste, test. He claimed to be able to detect the odor or taste of the cow (cowy), the barn (barny), grass (grassy), and certain weeds (weedy) in the cows diet. I have never been an enthusiastic milk drinker and having an aversion to tasting raw milk, I never took the opportunity to verify these flavors.

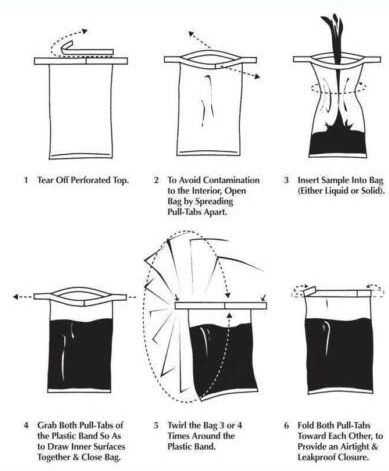

He would then place a sample in a twirl pack, label it and send it to the lab for approval. There were several tests it had to pass before approval could be made. The % solids had to be above a particular value. To do this test, we would pipette a specified volume of raw milk onto an absorbent fiberglass pad and cover it with another. Then into the microwave it goes. The microwave had a built-in electronic balance so it would readout the % solids directly after drying. This is done to detect shipments that had been diluted with water. Milk was bought and sold by the pound or hundred weight and it was not unknown for farmers in the past to “extend” the weight of their milk production with water.

The pH of the milk was taken as a cross check to be sure that fermentation wasn’t underway. When milk ferments, it gradually becomes more acidic and will keep going until the acid inhibits further growth. In days past it was not unknown for farmers to neutralize fermenting milk with NaOH or some other base. While this could put the pH back where it should be, it would affect the % solids and the flavor. It was a trick of last resort.

The raw milk sample was also tested for beta-lactam antibiotics by two methods before approving the tanker. Cows were prone to getting mastitis from an aggressive milking schedule. Excessive dosing of dairy cattle with antibiotics to get them back into production could lead to antibiotics showing up in the milk. The state regulators watched this closely.

We used a standard disk assay method looking for inhibition in the growth of bacillus stearothermophilus spores suspended in agar growth media (it has been renamed Geobacillus). A small disk of filter paper wetted with a milk sample was placed on a petri dish of B. stearothermophilus spores in agar was warmed for 3-4 hours at 50 to 60 C. A positive result would appear as an inhibition ring around the disk indicating suppressed microbial growth. This was always compared with a disk spiked with a standard. A positive result would be recorded if the inhibition ring around the sample was larger than the ring around the standard. This test took a bit of time so it was used mainly as a cross check for the “Charm” test.

A faster test for beta-lactam antibiotics was the Charm test. This test used a radiolabeled reagent that would indicate the presence of beta-lactam antibiotics in a test sample. The sample was placed on a planchet which was heated to dryness and then put in a radiation counter for a set period of time. The turnaround time was ~15-20 minutes. This allowed for faster approval. From a Google search, it doesn’t appear that this version of a Charm test is now in service. It appears that a test strip can be used instead.

In the dairy business the fat content of milk is very important. It is a milk component that can be isolated and used to produce high margin products like ice cream, novelties, whipping cream, coffee cream and half-and-half. Every day there is a milk fat budget that you must work within. Regular drinking milk, sometimes called fluid milk, is graded into fat content categories. There is 0.5 %, 1 %, 2 %, and what we referred to as “homo”, referring to homogenized, regular 4 %. All of the fluid milk is homogenized.

Babcock bottles for volumetric dairy fat analysis. Weber Scientific, https://www.weberscientific.com/babcock-test-bottles-weber

Once the raw milk is approved, it must be altered in a few ways to make it shelf stable and presentable. The more equipment milk passes through, the more chance there is to give it an off-flavor. It is homogenized to produce a uniform, stable dispersion. This prevents the milk from separating on storage to form a cream layer on top. Many people like having the cream separate from the milk, however.

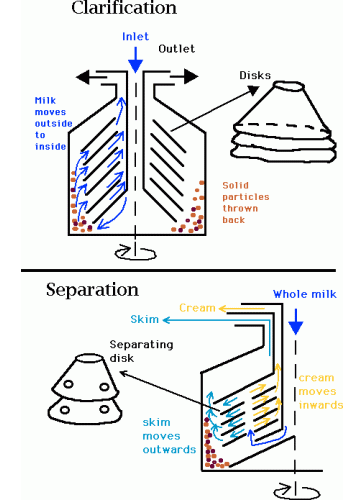

Early in the processing is the centrifugation step. Our plant had a centrifuge (“separator”) that would separate any solids present in the raw milk The centrifuge consisted of a stack of spinning conical plates that separated the cream as well as any solids present. The solids included cow hair, cellular matter, and dirt- stuff that you don’t want to dwell on. The fat content of milk skimmed in this way could be precisely controlled and operated on a continuous basis.

From the manufacturing point of view, processing and packaging an inhomogeneous mixture is a quality control problem. First, a continuous flow process works better if the composition of the material is uniform. Making sure that every customer gets their fair share of quality, creamy milk is important for making happy customers. Second, if the fluid milk composition is variable over time, it is hard to guarantee that you will recover enough of the valuable cream you want to divert for other products yet produce consistent fluid milk. In milk processing, consistency is everything.

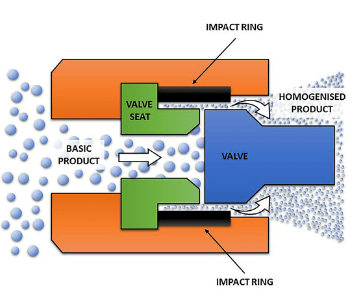

Homogenization of milk can be done in a couple of ways, but they all share the process of shearing a 2-phase liquid. A jet of milk can be aimed at a stationary plate. The shear in the fluid at impact can break up the fat globules into a smaller size to give a stable suspension. The more popular method is to apply shear by forcing the milk through very small openings at high pressure. Shearing a liquid is a stretching action on a parcel of the fat leading to dispersal of the fat globules into smaller droplets and better dispersion.

At some point milk producers discovered that there was a market for low fat milk. Producers were happy to expand into this market because it would bring diet-conscious customers back into consuming fluid milk. Milk was commoditized long ago so there are many competitors out there grasping for your dairy dollars. For producers, low fat milk is an opportunity to direct excess dairy fat into more profitable products while keeping the volume in fluid milk sales up. A steady flow of commodity product is always a good thing for a business.

In production, milk fat content is something that has to be carefully managed. X pounds of dairy fat come into the plant every day and X (minus losses) pounds go out as product. You want to produce as much high margin, high-fat product as possible but you must also stay competitive in the fluid milk business. Commodity fluid milk keeps stable cash flow and your valuable shelf space in the supermarkets.

When the tankers come in at 4:00 am you want to get a fat content for the accountants and the plant managers. We paid for raw milk on the basis of fat content and weight. The standard fat test method we used was a volumetric test called the Gerber method. We would combine a standard volume of milk with butanol and fairly concentrated sulfuric acid in a Babcock bottle and heat it. We would then spin it in a centrifuge to separate the fat layer from the acidic layer. The fat would rise into the calibrated neck of the flask where we would directly read off the value using a caliper. The butanol helped to clarify the fat layer.

On occasion the plant’s fat budget would get misaligned and milk fat (cream) would have to be tanked in from elsewhere.

The plant produced about 1 million small dairy creamer cups per month that are for a single portion of coffee. The creamer fat % was determined for the batch, not individually. Samples were, however, individually tested for bacteria and taste and taken every 15 minutes.

We produced sour cream using active cultures for fermentation. We packaged sour cream as well as several flavors of potato chip dip. Chip dip is just sour cream flavored with solid spices. It is interesting to note that active bacterial cultures can become infected and die from a virus called a bacteriophage or just “phage“. Having a phage rampaging through your fermentation and packaging operation is a serious problem. You must shut everything down, maybe dispose of your raw materials and the latest product lots, and then hit everything with bleach and scrubbing and then restart with close attention.

We produced whipping cream and half-and-half. The whipping cream was produced as a heavy whip with about 36 % fat. Half-and-half was around 12 % fat. These two products were sold as sterile products meaning that they were, unlike fluid milk, completely free of bacteria. More on that in a bit.

Pasteurization of milk was an important improvement that dramatically improved the shelf-life of dairy products as well as reducing the incidence of milk-borne infection. In times past, milk-born illness was a serious problem. Today it is only greatly attenuated, not eliminated. Milk is an excellent growth medium for microorganisms like bacteria, yeasts and molds. There is water, fats, proteins and sugars. The udders of a cow are low to the ground and back where the manure comes from. Contamination of the udders is a given. Good sanitation from the udders to the consumer must be in place at all times.

Back then, the word was that it took about 2000 bacteria per milliliter to cause an off-flavor. However I cannot verify this.

The trick to milk processing is to avoid contaminating it during manufacture and packaging. Bacteria, yeasts and mold spores are in the air and everywhere else. We assayed for general microbial contamination and specifically for E. coli. The general assay was for the general hygiene of the plant and raw milk. The E. coli testing was used to gauge the microbial contamination from the operators. Humans harbor coliforms naturally in the gut. We live with them in harmony. They crowd out pathogenic bacteria for us and in turn we feed them. However, if our personal hygiene habits are poor, coliforms will show up in the product. The hands are the usual source of contamination. It must be understood that not all coliforms are pathogenic. Occasionally a pathogenic strain shows up and spreads around, making people very sick or worse. Unfortunately, these bad strains are only discovered after people start getting sick. So, as a kind of canary in the coal mine, coliform tests are used to measure the processing hygiene of the process.

The state health department was always very interested in coliform contamination. They would collect dairy products from the supermarket and test them for coliforms. A bad result would immediately cause the heat to be turned up on the plant managers. It was infrequent but taken very seriously. It usually pertained to cottage cheese. Cutting and collecting the curds was a manual operation, though the operators always wore gloves. The health department could embargo a plant’s output from the market for repeat offenses.

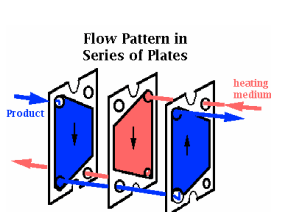

In common use is the HTST, High Temperature Short Time, method of pasteurization. HTST involves a short contact time of fluid milk with a moderately “high” temperature surface. This was done in a “press” which was a horizontal stack of alternating plates through which a heat transfer liquid and fluid milk would pass. The plates were compressed with a screw device holding them together under pressure- a press.

Be sure to understand that pasteurization does not equal sterilization. There is pasteurization and there is ultra-pasteurization. The first is an attenuation of the microbial load. The second refers to sterilization from ultra-high temperature, UHT, processing. In the case of American fluid milk, the kind that requires refrigeration, it is attenuated only. It is not sterile. This milk is usually good for 1 week past the expiration date if it has been constantly refrigerated. If it has been warmed to room temperature, then it is good for about 1 day, give or take. When a bacteria culture grows, the population rises slowly for a short time and then ramps into what is called the log phase (logarithmic growth). The population of bacteria grows via binary fission which is exponential growth. This situation leads to spoilage.

Milk and other dairy products that do not require refrigeration have been ultra-pasteurized by UHT. This is a bit delicate because too much contact time could lead to caramelization of the milk. These products should be sterile and an unopened container should have a long shelf-life at room temperature. Once the container is open and exposed to anything external it is subject to microbial growth.

The automated packaging equipment would spray in a small shot of concentrated hydrogen peroxide (~35 %) into the empty packages in an effort to cut down on microbial contamination just prior to the filling stage. Hydrogen peroxide is unstable in milk and decomposes quickly. Unfortunately, some bacteria have catalase which rapidly decomposes hydrogen peroxide into oxygen and water, thereby making them resistant to the sanitizing effect of the peroxide. Some bacteria, like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are resistant to hydrogen peroxide.

On one occasion we encountered agar plates from a fluid milk sample that became green after the normal incubation. We had never seen this before. I opened a dish and took a whiff. It was fruity smelling. Since I had taken microbiology as an elective as an undergrad (chem major) I was aware that Pseudomonas aeruginosa was famous for its fruity smell, but cultures of it were blue. I performed a catalase test by pouring some hydrogen peroxide on the plate and the peroxide immediately began to fizz- positive result. This was consistent with P. aeruginosa. But why was the plate green? Well, when you have a bacterium that produces blue colonies in a yellow agar medium, you get green. Presto, we identified it. We dumped the lot and cleaned the equipment and never saw it again.

Our ultra-pasteurized products were sampled by taking packaged milk off the packaging line every 20 minutes and putting it into a 90 F hotbox for 48 hours. After the time was up we opened each container and put a sterilized loop into it and inoculated an agar plate. Then the containers were each tasted by the lab tech (me) for any off flavors. Most samples passed both the microbial and the taste testing. Usually there were several in the 4 or 5 milk crates that were bad. I’ve never been a big fan of milk when even it is cold, so this warm milk at the end of its shelf life was no picnic. We would open a carton, take a swig and hold it long enough to pick up the taste, then spit it into the sink, holding back the gag reflex all the while. We tended to do this rapidly to get it over with, but in doing so we would occasionally get a mouthful of sour milk with chunks or just whey. Both would be carbonated and tangy from fermentation and sometimes show stormy fermentation. It was gross and disgusting. Heavy whip that was clean would sometimes be surreptitiously churned into butter by a certain lab tech who was eventually caught and fired. He was handing it out to folks in his church. Management said it was a case of a dairy product of unknown quality leaving the plant. Yeah, Ok.

UHT fluid milk stored at room temperature is popular in Europe and a few other countries but not so much in the US. I guess we’re just squeamish about milk here. I know I am.

Our plant also produced cottage cheese. No big mystery here. We filled a rectangular vat with warmed skim milk and added a mixture of weak acids to it. I recall that the curdling acids was a mix of phosphoric and lactic acids. This method was known as “direct set.” After a short time the milk curdled with the white curd floating as a solid mass in the yellowish whey. The operators would use a multibladed knife the cut the curds into cube shaped chunks. Then the whey was discarded into the sanitary sewer and the curds were washed and loaded into a machine for packaging. Most cottage cheese was blended with a salted cream to give it a creamy texture. Some of the curds were packaged as “dry curds”.

For a long time the plant would send the whey from the cottage cheese process down the sanitary sewer. Then one day we were given a very large sewer bill. It had jumped from $2,000 to about $26,000 per month. You could hear a clattering noise from all of the bricks the accountants were shi**ing. The giant invoice was for all of the biological oxygen demand (BOD) that our whey was actually consuming at the sewage treatment plant. The folks at the treatment plant had been noticing that the BOD of the sewage going into the plant had been swinging around but couldn’t figure it out. Then one day they noticed that the problem popped up when they saw cheese curds floating in with the waste. They connected the curds and presented us with a hefty bill for the plant capacity we were consuming by dumping whey down the drain. Soon thereafter we sold the whey to hog farmers. Whey has a few percent of protein content. The farmers were happy but we never heard what the pigs thought.

Finally, we had a juice packaging operation. We produced orange juice and a small portioned flavored beverage that went by some childish name. We bought orange juice concentrate in 55 gallon drums and would just dump it into a mixing vat and dilute it to spec. Easy peasy. It would then go to packaging in the isolated juice room. Same with the other beverage. I think we had more contamination issues with the juice than anything else. The juice was especially prone to going off from yeasts and molds. There was usually gas generated that would bulge the containers. This became a serious shelf-life issue when it happened. Instead of bleach they cleaned the juice room with quaternary ammonium based cleaning agents (“quats”). I think we mistakenly thought that the contamination came from us. It could have been spores riding along with the concentrate. We never tested for that.

We had a large, chilled warehouse held at 38 F for storing product. We also had a cold box at -40 F for warehousing ice cream from another plant. The plant was also a distribution center. The chiller plant used ammonia. When it needed maintenance, it was critical to get a reefer guy who would work on ammonia systems. Not everyone will do this.

I learned a bunch and grew from doing this work. I don’t think I’ll go back though.