Notice: As an organic chemist and not a geochemist I will be using descriptions and vocabulary that may not ordinarily be used in geology. While a geochemist might easily write a lovely article that could bring tears to the eyes of the most sour geochemist, I will stumble forward with just my trailer park chemistry background- organometallic, organic, inorganic, physical and quantum chemistry.

When you step back and view mining technology as a whole, it becomes apparent that two of the largest scale inputs in mineral refining are water and electrical energy. On Earth diesel is also required in large quantities.

A good question for those who propose mining asteroids is this: Have you solved the water and electric power requirements for unit operations? Let’s say it is solved for one mineral. How will the value be mined, transported and gently lowered to the Earth’s surface without breaking into flaming pieces on re-entry or forming a crater in a city? Is there an element or mineral that is so valuable as to justify the costs and risks to be met for a space mining mission? Is it rhodium? Gold? Diamonds? Or what?

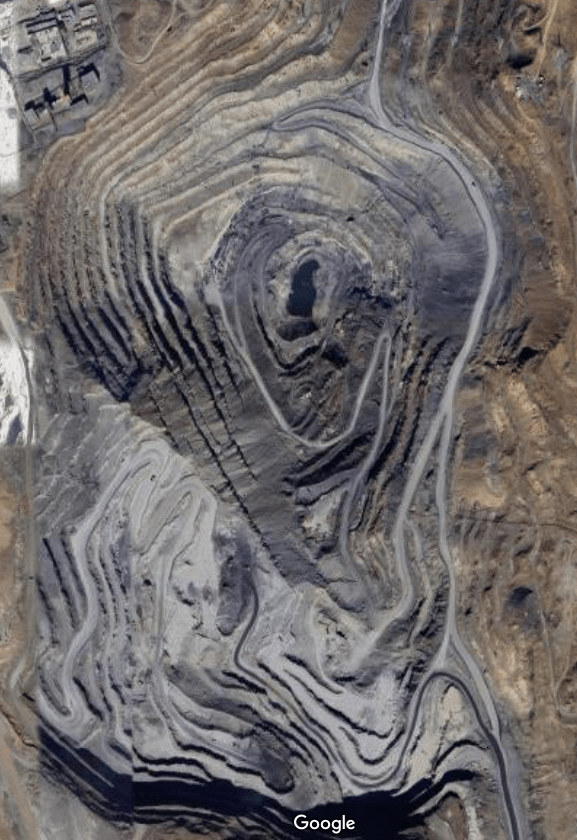

Do the people behind the fanciful images and hype believe that they only have to dock with the asteroid and grab valuable minerals from the surface? There is a good chance that the target ore will need exploration, excavation, and possibly some kind of blasting. The target elements may well be dispersed within the host rock. This will require comminution in preparation for further processing. The ore will likely need ore dressing which is the job of removing undesired rock from the valuable ore. This lowers the quantity of ore to be processed.

The rocky bodies in the solar system have surfaces of regolith. Regolith is an unconsolidated jumble of loose rock and dust presumably overlying a solid body. Given that the regolith may well be consist of rocks and dust accreted from a distant source, merely assaying the regolith might not reveal the minerals that could be there in abundance just below the regolith. There is no way around it- core samples will be needed to properly assess the economic geology.

PGM Mining on Earth

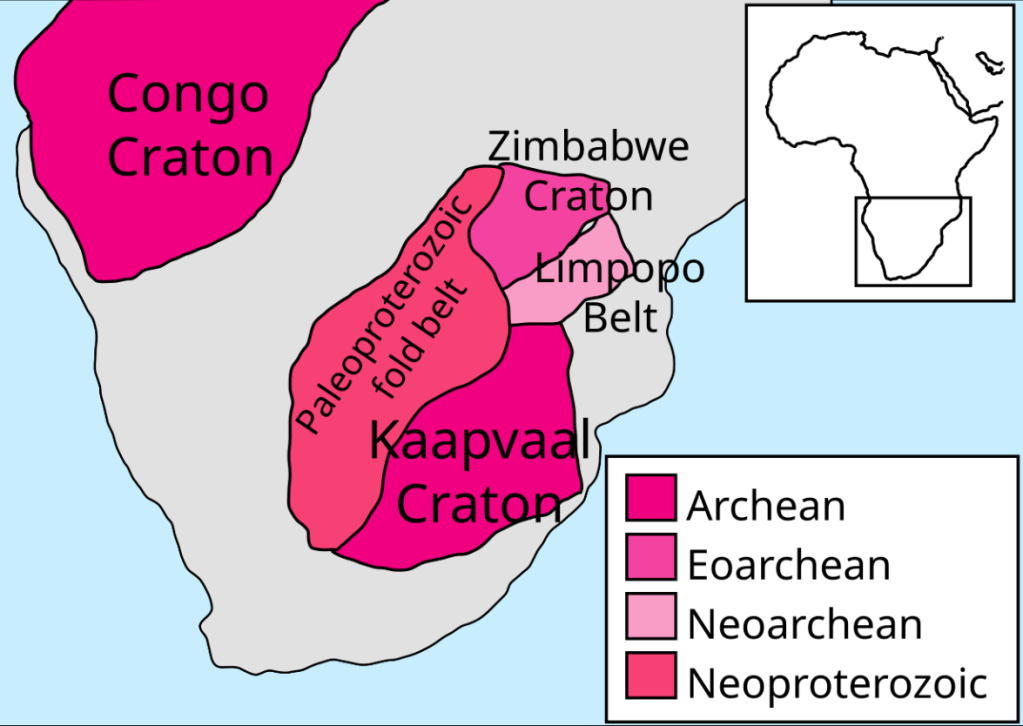

A look at the large-scale Platinum Group Metal (PGM) production activity in South Africa is instructive. The Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC) near Limpopo and North-West provinces contains some of the richest PGM deposits in the world. The BIC is found in the Kaapvaal craton. The BIC also extends into Zimbabwe.

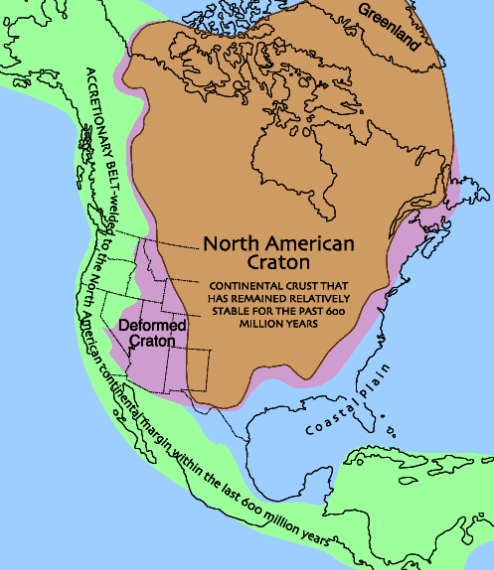

The Bushveld complex is located on a ‘craton‘ which is a section of continental crust that has been stable for 400 million years or so. Over that time period some portion of crust has not been subjected to subduction or rifting as an effect of continental drift. A craton is relatively untouched by continental drift over some lengthy time interval and as a consequence the crustal rocks found in a craton may be quite old. Here, ‘old’ means rock that has not been metamorphosed recently, vented out of a volcano or eroded and stratified in a sedimentary formation within several hundred MA.

The Bushveld complex is found in the Kaapvaal craton of South Africa, extending into Zimbabwe. A consequence of this location on a very stable parcel of continental crust is that vertical transposition of rock formations, i.e., subduction activity, has not led to metamorphism or folding of strata. This stability has allowed a relatively undisturbed magma chamber to form and cool, producing layered cumulates.

The formation of cumulates is a partitioning process within the magma chamber that produces solid minerals that can float or sink within the magma. Cumulates with higher density than the magma will tend to sink, building a layer, and lower density minerals will float to the top of the chamber and form an upper layer. In this way, minerals can self-purify and stratify by fractional crystallization.

While fractional crystallization can result in enhanced purity of specific minerals, the melt from which the crystals precipitate is also changing in composition. Magma is a viscous fluid and its components can undergo anion/cation exchange to produce new minerals upon further cooling. Anions include silicate, aluminate, sulfide, hydroxide, chloride, oxide, and a whole basket of metal oxyanions like titanate, tungstate, molybdate, chromate, etc. Cations include most every metal, sometimes including the noble metals. Every metal has a set of positive oxidation states that may be subject to reduction or oxidation to afford a different oxidation state or charge.

While both anions and cations present in magma have a particular charge, their individual size is important as well. Size and charge matter most when crystals are assembling. When, for instance, a calcium-containing mineral is crystallizing, the crystal lattice is subject to collisions with the whole gamut of species in the magma. If the temperature and pressure are appropriate, calcium (+2) cations nestle into a vacancy in the lattice. This is controlled by the concentration, temperature and Gibbs energy of the placement of the cation. However, if a different cation of +2 charge and similar ionic radius happens by, that different +2 cation may find itself occupying calcium’s place in the lattice. An example would be where the Ca+2 cation was replaced by Mg+2 or Fe+2.

Mineral crystal formation is a type of equilibrium wherein lattice anions and cations at the surface of the crystal are in equilibrium with anions and cations in the melt. The rate of crystallization or dissolution is driven by several things. Substitution of a Ca+2 ion in a lattice with Mg+2 or Fe+2 ions retains the charge balance in the lattice. But if a too large or too small +2 cation attempts to sit in place of Ca+2, a mismatch occurs which may be energetically favorable, but as a result may be much more prone to removal by equilibration. The interloping cation could be of such a size that its heat of formation is small and therefore subject to replacement by equilibration. Or not. The resulting mineral could be comprised of Ca+2 cations and M+2 cations in a non-stoichiometric ratio. Or a new mineral comprising a stoichiometric ratio of both cations.

The anions in a mineral substance can be quite varied and several may exist in a mineral at the same time as in the case of anions silicate and aluminate.

The Stillwater Igneous Complex in Montana, USA; the Sudbury Basin in Canada; and the Norilsk-Talnakh deposits north of the arctic circle on the Siberian Craton.

Russia is the leading producer of palladium with 40 % of the global market. Norilsk Is also known as a center of non-ferrous metallurgy as well as noble metals. Norilsk Nickel, also known as Nornickel, is a mining and smelting company. Platinum Group Metals (PGM) have been recovered as a side stream of nickel and copper mining by Norilsk Nickel.

The aerospace proponents of asteroid mining should spend some time at an actual mine. Breaking rock and hauling it around is simple on Earth but consider doing this in a vacuum at near-zero gravity. Look at all of the methods of conveyance and processing in operation at a mine that works only in a gravitational field. Blasting, front-end loaders, haul trucks, conveyor belts, crushers, ball and rod mills, flotation and settling tanks, lixiviation in sulfuric acid and several shifts of staff to operate and maintain it. Don’t forget the analytical lab and chemist or the maintenance group.

Proponents will always say that with the right technology, asteroid mining could work. But in the airgap between could and will is the nagging question of why? Maybe asteroid mining is best left to our descendants in the 22nd century.

A human trip to an asteroid, which is always in orbital motion and probably rotating, to mine and return with paydirt for the investors will always be high cost. Bodies outside of the Earth-Moon system will be nearby only for a short time, depending on the orbital period of the asteroid. While our Earth is measurably overheating, the biosphere is disintegrating and political turmoil is rampant on Earth, perhaps we should focus closer to home?

Humanity must stay focused on critical housekeeping activity here on planet A. Monetizing the outer worlds can wait.

I do believe that eventually somebody will design mining technology to solve the unique problems of mining smaller asteroid bodies with negligeable gravity. Energy dense power sources will be needed to move commercial scale machines and ore. The big problem will be the economics. What mineral is so valuable as to justify the trillion-dollar expense of finding an asteroid with suitable quantities of mineral, up front R&D costs, and beneficiation and isolation of the mineral?

Minerals dispersed in the regolith matrix will need comminution, extraction by lixiviation, floatation, isolation and packaging. Now, we can get it back to earth orbit but then what? Do we just deorbit in the usual way?

Bringing home the paydirt

Let’s say they return 1000 kg (contained) of rhodium valued at todays price of $5400/toz (toz = troy ounce). 1000 Kg contained of rhodium = 32150.7 troy ounces, so 32150.7 toz x $5400/toz = $173,613, 780. However, just the rumor of 1000 kg of new rhodium about to come on the market will drive rhodium prices down. So, $174 million sounds like a lot of money and in a sense it is. But in aerospace and heavy industry, millions are quickly consumed.

Rhodium was chosen for its general scarcity and high price. There is no reason to suppose that rhodium will be more abundant on a given asteroid than on earth so numerous asteroids may need exploration by geologists. Core samples might be needed for the economic geologists to sketch out the size and value of an ore body.

There will be a threshold price of rhodium that must me exceeded before rocket launching and asteroid digging begins. This is how mining works on earth. Until then, the celestial rhodium discovery will just keep orbiting the sun into the future.

An aspect of PGMs is that the very few mines that produce them do so in a unique geological feature on a craton. The mechanism for PGM mineralization in districts like the Bushveld Igneous Complex in South Africa took place in a magma chamber where over time the magma began to cool. Magma gets its minerals from the mantle far below and from the walls of the magma chamber. In subduction zones the subducting crust is pushed downwards causing rising temperatures.

Subducting oceanic crust is loaded with water in several forms. Many minerals are ‘hydrated’ meaning that one or more water molecules are strongly attached to the mineral. These might be called coordinated water. The oxygens are strongly attracted to a cationic feature of the mineral. Interstitial water molecules may be occupying voids in the mineral lattice. Discrete water is only weakly attached and may diffuse elsewhere. Interstitial and discrete water may evaporate readily if exposed to air or heat. At the elevated pressures and temperatures of magma at depth, the three kinds of water are hot enough to flash to steam if the pressure was released. However, as the magma rises to the surface to cooler surroundings and lower pressures, eventually the water will flash to the gas phase moving magma in the direction of lower pressure. Just below the surface the dissolved gases including CO2, steam and SO2 will expand as a gas and push magma to the surface causing a volcanic eruption.

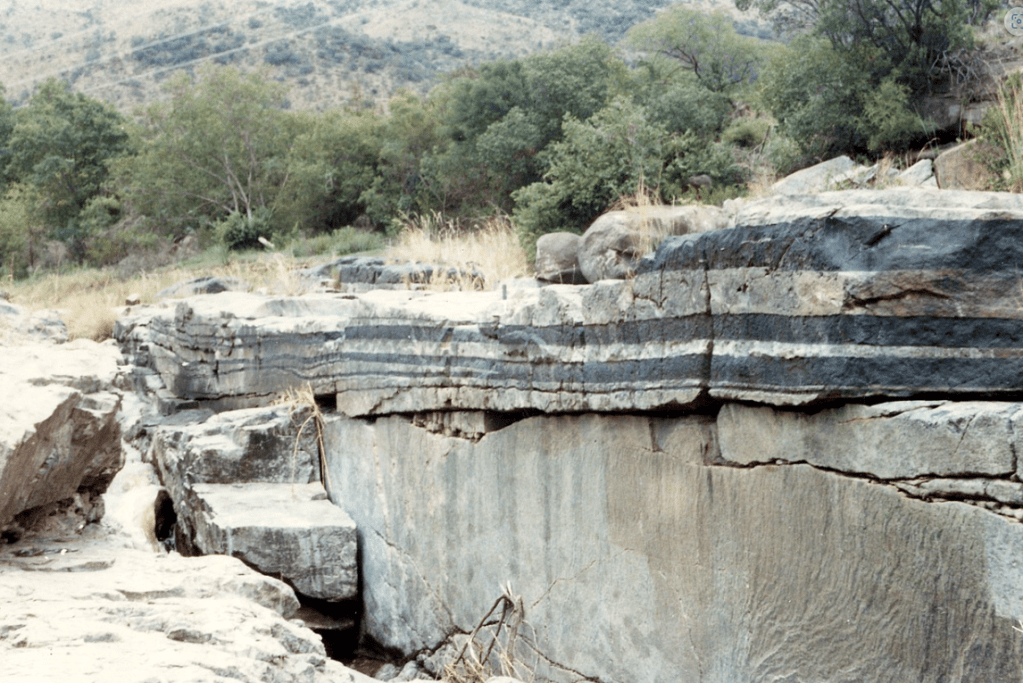

As the magma cools, the substances with the highest melting point begin to crystallize. If the crystals that have a higher density than the magma, they will settle lower in the magma chamber and form a distinct layer. While this layer is building, other minerals will follow in a similar process. The layers of precipitated minerals are called cumulates.

The process of minerals selectively crystallizing and precipitating to the upper or lower zones of the magma chamber. The overall process is called fractional crystallization and layers called cumulates can form. In the photo below are several layers of dark chromite cumulate.

Now that I have expressed my doubts about asteroid mining, I must ask ‘Am I being a Luddite’? Maybe a little bit, but even the doubts of a Luddite can be on the mark now and then. Asteroid mining will be an adventure for a few astronauts, profitable for aerospace contractors and an entertainment spectacle for the public; however, resources seem better used on Earth for remediation of the biosphere, diplomatic solutions for the conflict of the week, lower hydrocarbon consumption and better education, especially in the area of civics.

The whole purpose of mentioning PGM geology and mining in a post titled Asteroid Mining is that we on Earth are fortunate to have concentrated mineral deposits that exist only because of unique geological processes. These processes only work in Earth’s gravitational field. The upwelling of lower density hot hydrothermal fluids. The formation of evaporites rich in borax. Lithium brines.

Take my uranium, please

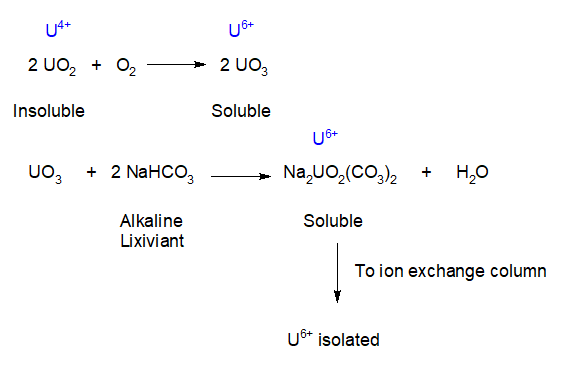

The formation of cumulates in lava chambers relies on differential density driven by gravity. The ability of rain and snow runoff to mobilize gold sulfides will produce lode gold and placer deposits. The ability of oxygenated meteoric water to oxidize insoluble U4+ to soluble U6+ in sandstone formations to form concentrated roll front deposits. The ability of oxygen to switch uranium oxidation states from U4+ to produce a soluble form (U6+) that can migrate and concentrate leading to the partitioning of U6+/U4+ species. Underground formations of uranium can be dissolved in a solution of sodium bicarbonate by injection and pregnant solutions of the uranium carbonate can be brought to the surface as a solution. This solution is run through a column of ion exchange resin beads which exchange chloride ions for the uranium complex. Once loaded, the beads are washed with a special solution to remove the uranium (6+) concentrate.

Our ability to mine and isolate minerals is uniquely enabled by planet earth. The ability of nature to dissolve, mobilize and concentrate minerals into ore bodies from highly dispersed placement in source rock has been positive for humanity. A great many elements are found in a dispersed condition in the continental crust. For some, there are natural processes for concentration. For others, they form secondary minerals that end up mined with the primary ore. A few like gallium, indium and bismuth are valuable but are only available as a side stream from the primary ore. Copper is an excellent example of a primary metal whose ore includes many other metals like zinc and bismuth. Copper can be electro-refined to 99.99 % purity. The slimes left behind after the electrolysis and dusts caught in ventilation systems can be enriched in useful metals and are often collected for processing.

The purpose of citing the large-scale processes in use on the home planet is not to suggest that asteroid mining must start out at large-scale. It would likely start out as a small-scale surface or underground operation with a small crew or with robotics. Only a few select minerals would be economically suitable for recovery. Platinum Group Metals are mentioned above because of their high intrinsic value and ability to exist as the native metal. If luck is with the astro-miners, the motherlode might be easily visible so later the gangue material can be chipped off. The process of trimming ore to retain the value and discard the gangue was called ore dressing. Being quite dense, the volume of PGM metal ore may be low, but the density and mass is quite high.

If a given asteroid has never been part of a larger system with magma and sufficient gravity to force stratification by density, the cumulate model may not apply. A given asteroid having never been exposed to bulk water and consequently never been subject to hydrothermal flows and weathering may not have minerals that here on Earth are known to be formed with water or partitioned as a result of hydrothermal flows. Lake and ocean sedimentary units are almost surely absent as are processes requiring aqueous migration through porous rock as in the case of uranium roll fronts.

Asteroid mining will be a totally new activity and most all of the natural geological processes on earth will have been absent. Many geological processes on earth produce economic ore bodies. These will be largely absent on an airless, dry asteroid.

One thing to consider: Most of the rock accessible at the Earth’s surface is not economic ore. The surface of the Earth brimming with carbonates, silicates and aluminates bound to a variety of ‘ordinary’ metals like calcium, magnesium, iron, sodium, potassium and a handful of other common metals. While there are important and valuable uses for these common metals, they are predominantly found dispersed in surface rock comprised of many individual minerals, or that an ore body is too small for economic recovery.

The fraction of the desired mineral in the ore can be highly variable. Depending on the market, some parts of the ore body may be economical to mine while other parts may not. This is why cores are drilled to locate the 3-dimensional extent of the ore body, estimate the potential value and minimize the expense of digging and processing uneconomical ore.

It seems reasonable to suppose that, just as much of the surface of the earth is covered with rocks made from mineral constituents of low economic value like crushed roadbed rock or sand and cement for concrete use, why should we assume that a given asteroid would be any better endowed with value than Earth’s surface? Asteroid mining will necessarily be preceded by expensive exploration. Obviously, right? But it means that considerable money and time will be spent up front finding an asteroid that is sufficiently ‘pregnant’ with valuable metal ore. Finding investors to fund exploration and mining development today is based on economic geology surveys and signed off by certified experts.

A mine is a hole in the ground with a liar standing at the top. –Attributed to Mark Twain

On Earth many mineral deposits have been located historically by surface exposures that are part of a larger ore body. The economics of isolating any one mineral or metal in the presence of the others will depend heavily on the % concentration of the target mineral, the processing methods available and the market price of the final product. A market downturn can last months, years or represent new long-term realities in demand for the product.

What a party pooper you are. I just sunk the greater part of my retirement IRA into an asteroid mining IPO promoted by Elon Musk. What could possibly go worng?

What a party pooper you are. I just sunk the greater part of my retirement IRA into an asteroid mining IPO promoted by Elon Musk. What could possibly go worng?

If only Iron and Nickel were really expensive….

There is reason to suppose rhodium would be more abundant on an asteroid than on Earth. Platinum group metals are more abundant in asteroids than on Earth, in fact the average concentrations seem to be be higher than in ores on Earth, but we are still only talking about 230 ppm total Pt group metals at most so the problems you raise are still valid.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032063322001945

Hello AChemist,

Thank you for your comments and the excellent link. My motivation to write this post arose from the realization that a great many terrestrial economic metals reside in crustal deposits that have been subject to concentration by hydrothermal fluids or by cumulate processes in the melt. It’s hard to say if a given asteroid has been subject to the mechanisms of ore body formation such as those here on Earth. Whether or not an economic metal is in a discrete ore body or disseminated throughout the rock formation will make a large difference in the cost of production. If the market price of a metal drops sufficiently, the metal may have to sit in place until the market price increases past a profit margin threshold.

The formation of concentrated ore bodies on Earth was determined by chemical properties like solubility, Gibbs energy of formation, melting temperatures, density and the types of anions (silicates, carbonates etc.) and cations (metals) present. This concentration process greatly affects the economics of mining the PGMs. For most mining of specific minerals, there is likely a target metal-to-ton of ore ratio that determines the economic viability of mining the deposit.

What if a probe samples an asteroid surface and finds a peak concentration 600 ppm in 1 out of 5 samples? of a PGM like rhodium? What would it take to go forward with mining operations? How much ore dressing or early-stage beneficiation is possible in the microgravity of the asteroid or on a processing craft? Would any beneficiation be possible in space?

I do not believe that asteroid mining is impossible or even improbable, but backers of this should pick a few minerals to see what kind of beneficiation and refining is required. Refining of PGMs seems likely to be a ground-based operation based on the pyrometallurgy often needed.

Based on deposits on earth, the high value rhodium target is unlikely to be the only PGM present. In fact, Rh is usually a minor constituent in PGM ore with platinum and palladium as the major PGMs present. Given this assumption, the high value of rhodium will be “diluted” with PGMs of lesser value. While not necessarily a disaster, the PGM mixture will require refining by skilled operators on Earth. This is known technology.

When it comes to rhodium as the target metal, the fact is that Rh is usually found along with other PGMs. The recovered concentrate will need to land softly on earth. If the asteroid is further out from the sun than Earth, it will have more kinetic energy to dump on return than an object in low Earth orbit.

Instead of Rh mining it would likely be PGM mining producing Platinum Group Metals.