The news service Reuters recently published an article on the ease with which the raw materials for the production of the opioid Fentanyl. From their $3600 expenditure on raw materials they estimate they could have produced $3 million worth of Fentanyl.

For an estimated 74,702 Americans in 2023, Fentanyl provided them with a narcotic experience prior to death. The lethal dose is reported to be 2 milligrams for an adult. It is 20 to 40 times more potent than heroin.

Outside of medical use Fentanyl should be described as a highly (neuro)toxic substance rather than just an opioid. Yes, it is an illegal narcotic, but it is also a potent deadly poison. Hidden with other illegal drugs in pill form, it is just a highly toxic contaminant.

On January 5, 2024, I posted a piece titled “A Bit of Fentanyl Chemistry” which is reproduced below. It turns out that the Janssen synthetic chemistry I wrote about then is quite close to what the investigators at Reuters had in mind for their story. In the world of chemical commerce, a process using easily available raw materials is highly favored.

My take-home message from the Reuters story is that unless China seriously clamps down on those who export the raw materials, all that is left to do is to suppress demand. The import of Fentanyl raw materials is aided by deceptive packaging and small quantities needed. Worse, Fentanyl raw materials have other uses in pharmaceutical chemistry and are too useful to completely shut down. The death and incarceration that Fentanyl can bring in the US does not appear to be sufficiently convincing to the at-risk American population. Nothing new here.

=========================

A recent raid on a clandestine drug lab in the Hatzic Valley east of Vancouver, BC, netted 25 kg of “pure” fentanyl and 3 kg which had already been cut for street use. Precursor chemicals used to manufacture the fentanyl were also seized. Along with the drug, the raid also seized 2,000 liters of chemicals and 6,000 liters (about 30 drums) of hazardous chemical waste, according to an RCMP news release 2 November, 2023.

The police said that the seizure represented 2,500,000 street doses.

In August of 2023 the police in Hamilton, Ontario, announced the results of Project Odeon. This was a large-scale sweep of illicit drug production in the Hamilton and Toronto area. From January 1, to July 30, 2023 there were 606 incidents related to suspected opioid overdoses and 89 suspected drug related deaths in the Hamilton area. Twelve people were charged for a total of 48 criminal charges. The police disclosed the following items that they seized-

- An operational fentanyl drug lab at 6800 Sixteen Road, Smithville.

- A dismantled fentanyl drug lab at 4057 Bethesda Road, Stouffville.

- Approximately 3.5 tons of chemical byproduct from fentanyl production.

- 800 gallons of chemicals commonly used in the production of fentanyl

- Lab equipment commonly used in the production of fentanyl

- 64.1 kg of illicit drugs, including 25.6 kg of fentanyl, 18 kg methamphetamine, 6 kg of ketamine

- A loaded, Glock firearm and ammunition and four extended magazines

- Over $350,000 of seized proceeds, including cars, jewelry, furniture and cash

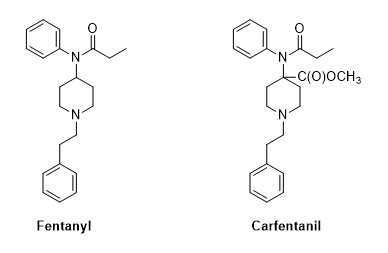

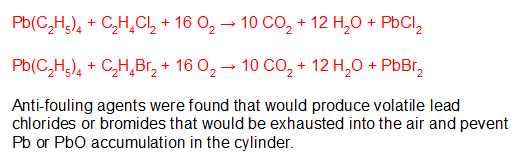

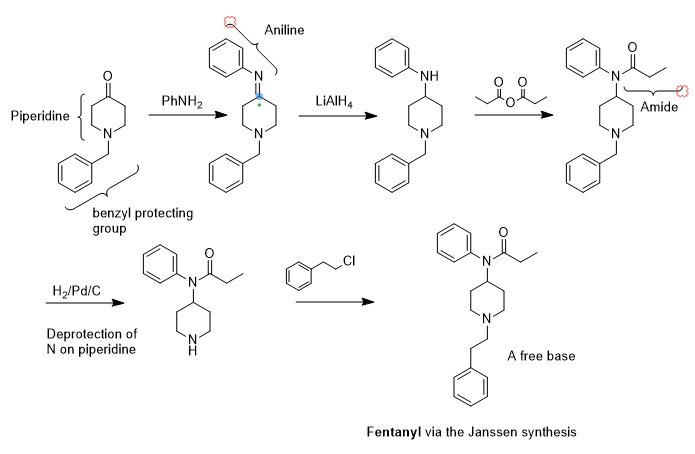

Fentanyl is a synthetic drug first prepared in 1959 in Belgium by Paul Janssen (1926-2003). Janssen was the founder of Janssen Pharmaceuticals, now a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson. In addition to fentanyl, the Jenssen team developed haloperidol, the ultrapotent carfentanil, and other piperidine based congeners. Piperidine itself is a DEA List 1 substance in the US.

The elephant in the room with fentanyl is its extraordinary potency as an opioid. In pharmacology, potency is a quantitative measure of the amount of dose needed to elicit a specific effect on an animal or human in terms of dose weight per kilogram of body mass. Potency is subject to variability across a population and rises to an asymptote which can be difficult to pin down. For these reasons potency is reported at 50 %. For highly potent drugs like fentanyl, the measure is expressed as milligrams or micrograms of dose per kilogram body weight (mg/kg or mcg/kg body weight). One milligram per kilogram is one part per million (ppm).

When matters of toxicity arise, it is important to remember the maxim that “the dose makes the poison”. This observation traces back to Paracelsus in the mid-sixteenth century.

“All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison.”

– Paracelsus, 1538. Source: Wikipedia

Fentanyl acts much like morphine in regard to its affinity for one particular opioid receptor. Morphine is commonly the “standard” with which other opioids are compared. For instance, fentanyl is said to be 50-100 times more potent than morphine. Only 2 mg of fentanyl is equivalent to 10 mg of morphine. Carfentanil is more potent still at 10,000 times the potency of morphine.

Morphine is an agonist which activates the μ-opioid receptor. Activation of this receptor with morphine produces analgesia, sedation, euphoria, decreased respiration and decreased bowel motility leading to the earthly delights of constipation. Fentanyl is thought to interact with this receptor as well.

So, how is fentanyl synthesized? See the synthetic scheme above. I’ll just comment on the Janssen synthesis and some issues. I have no idea of how it is made out in there by the Mexican cartels and in ramshackle American trailer parks. The synthesis above has some steps that may be undesirable for backwoods or jungle operations like hydrogenation. In the first step, aniline will be needed to make the phenyl imine. It’s pretty toxic and stinks to high heaven. Next, lithium aluminum hydride is needed to reduce the imine double bond to an amine. This innocent looking grey powder is very hazardous and should only be used by an experienced chemist. It is also available as a solution in tetrahydrofuran. The next step is the formation of the amide with propionic anhydride. While the reaction entails a simple reflux, you still have to isolate the product. Once you have recovered the amide, the benzyl protecting group on the piperidine nitrogen must be removed. It allowed amide formation exclusively on the upper aniline nitrogen and has served its purpose. Finally, the piperidine nitrogen must be festooned with a phenylethyl group and phenylethyl chloride was used to afford the fentanyl product.

An excellent review of the pharmacology and drug design of this family of opioids, see Future Med Chem. 2014 Mar; 6(4): 385–412.

In chemical synthesis generally, substances are prepared in a stepwise manner and with as few steps as possible to give high isolated yields. To begin, one must devise a synthesis beginning with commercially available raw materials as close to the target as possible. If the product has many fragments hanging off the core structure, it’s best to solve that problem early. Synthetic chemistry is almost always performed in a non-interfering solvent that will dissolve the reactants and allow the necessary reaction to occur. A low boiling point is preferable for ease of distillation. An important side benefit from a solvent is that it will absorb much of the heat of reaction which can be considerable. Left on its own, a reaction might take its solvent to the boiling point by self-heating, generating pressure and vapor. The benefit from evaporation or reflux boiling is that as a solvent transitions from liquid to vapor there is a strong cooling effect which helps to control the temperature. An overhead condenser will return cooled solvent to prevent solvent loss.

You can do any chemical synthesis in one step with the right starting materials. Unfortunately, this option is rarely available. The next best option is to take commercially available starting materials through a known synthetic scheme. People who run illicit drug labs are never interested in R&D. They want (and need) simple chemistry that can be done by non-chemists in buckets or coke bottles at remote locations. Chemical glassware can be purchased but sometimes the authorities will be notified of a suspicious order. This is especially true with 12 liter round bottom flasks.

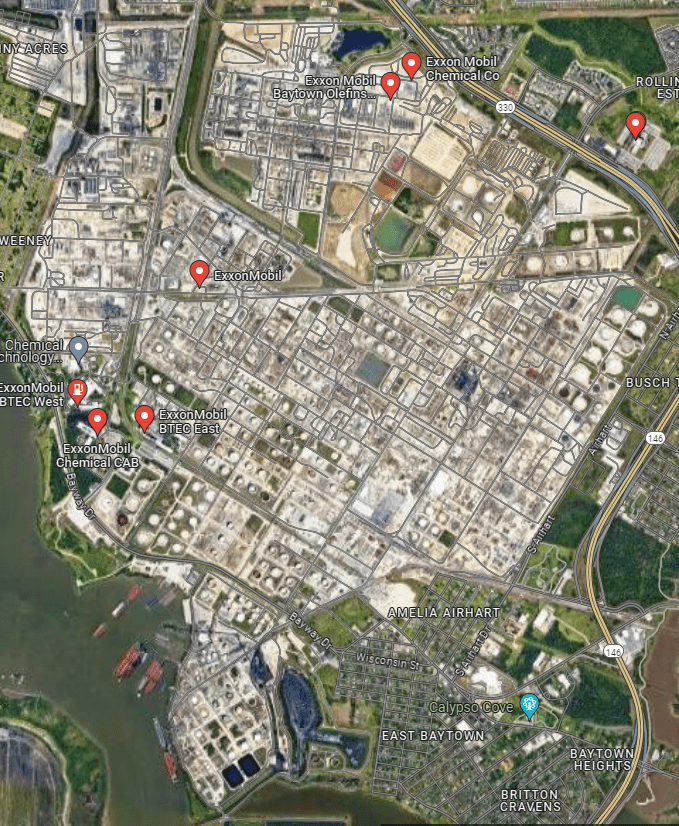

The most difficult and risky trick to illicit drug synthesis is obtaining starting materials like piperidine compounds in the case of fentanyl and its congeners. In the case of heroin, acetic anhydride shipments have been investigated for a long time because it is used to convert morphine to heroin- an unusually simple one-step conversion. Solvent diethyl ether is similarly difficult to get outside of established companies or universities. Many other common drug starting materials are difficult to obtain legally in the US or EU by the criminal element. However, China is thought to be a major supplier of starting materials outside the US and EU. Countries with remote coastlines, loose borders, lackadaisical or corrupt law enforcement reduce the barriers for entry of drug precursors.

China in particular has a large number of chemical plants that make diverse precursors for legitimate drugs. Unfortunately, some of these precursors can also be used for illicit drugs or existing technology adapted for this use. Precursors can be sold to resellers who can do as they please with them. Agents may represent many manufacturers and can mask the manufacturer’s identity and take charge of the distribution abroad. Shady transactions become difficult for authorities to detect and trace. The identity of illicit precursor chemicals are easily altered in the paperwork to grease the skids through customs. Resellers can repackage chemicals to suitable scale, change the paperwork and jack up the price for export. It has been my experience that many if not most Chinese or Japanese chemical manufacturers conduct business through independent export agents. However, behind the curtains there often a byzantine web of connections between companies and agents, so you may never know who will manufacture your chemical. As an aside, this complicates getting technical information from the manufacturer since the agent will not disclose a contact at that manufacturer.

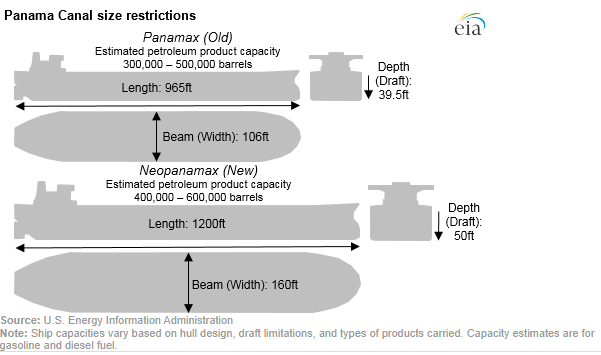

Highly potent drugs like fentanyl must be taken in very small dosages which means that kilo-scale batch quantities of drug result in many individual sales per kilo. Small quantities of highly potent drugs are more easily smuggled than bulky drugs like weed with its strong odor.

There is a down-side to the illicit manufacture of drugs like fentanyl. It is quite toxic at very low dosages and must be handled with the greatest of care lest the “cook” and other handlers get inadvertently and mortally poisoned. Good housekeeping helps, but I have yet to see a photo of a tidy drug lab.

Fentanyl can be sold as a single drug but perhaps is cut with a solid diluent that some random yayhoo decided was Ok to use. Other drugs of abuse like heroin may be surreptitiously spiked with fentanyl to kick up the potency. In either case, a given dosage may or may not be safe even for a single use. There is no way for a user to know. Also, the concentration or homogeneity of mixed solids may be subject to wide variation. For more than a few people, their first fentanyl dose will be their last.