Today I have a slightly different demographic of readers of this blog than in the past, so I’ve been dredging up old posts into the light of day. This is a renamed post from September 3, 2011. I’ve changed some wording to be a bit more mellifluous if that’s even possible.

==========

I’ve had this notion (a conceit, really) that as someone from both academia and industry, I should reach out to my colleagues in academia in order to bring some awareness of how chemistry is conducted off-campus. After many, many conversations, an accumulating pile of work in local ACS section activities, and visits to schools, what I’ve found is not what I expected. I expected a bit more academic curiosity about how large-scale chemical manufacturing and commerce works and perhaps what life is like at a chemical plant. I’d guessed that my academic associates might be intrigued by the marvels of the global chemical manufacturing complex and product process development. Many academics would rather not get all grubby with filthy lucre. Not surprisingly, though, they already have enough to stay on top of.

What I’ve found is more along the lines of polite disinterest. I’ve sensed this all along, but I’d been trying to sustain the hope that if only I could use the right words, I might elicit some interest in how manufacturing works- that I could strike some kind of spark. But what I’ve found is just how insular the magisterium of academia really is. The walls of the fortress are very thick. I’m on a reductionist jsg right now so I’ll declare that chemistry curricula is firmly in place on the three pillars of chemistry- theory, synthesis, and analysis. In truth, textbooks often set the structure of courses. A four-year ACS certified chemistry curriculum spares only a tiny bit of room for applied science. I certainly cannot begrudge departments for structuring around that format. Professors who can include much outside the usual range of academic chemistry seem scarce.

It could easily be argued that the other magisteria of industry and government are the same way. Well, except for one niggling detail. Academia supplies educated people to the other great domains comprising society. We seem to be left with the standard academic image of what a chemical scientist should look like going deeply into the next 50 years. Professors are scholars and they produce what they best understand- more scholars in their own image. This is only natural. I’ve done a bit of it myself.

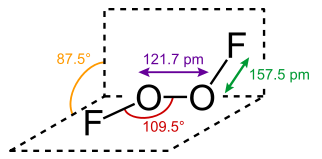

Here is my sweeping claim (imagine waving hands overhead)- on a number’s basis, chemists apparently aren’t that aware of industrial chemical synthesis as they come out of a BA/BS program. That is my conclusion based on interviewing many fresh chemistry graduates. I’ve interviewed BA/BS chemists who have had undergraduate research experience in nanomaterials and atomic force microscopy but could not draw a reaction scheme for the Fisher esterification to form ethyl acetate, much less identify the peaks on 1HNMR. As a former organic assistant prof, I find it sobering and a little unexpected.

A mechanistic understanding of carbon chemistry is one of the keepsakes of a year of sophomore organic chemistry. It is a window into the Ångstrom-scale machinations of nature. The good news is that the forgetful job candidate usually can be coached into remembering the chemistry. After a year of sophomore Orgo, most students are just glad the ordeal is over and they still may not be out of the running for medical school.

I think the apparent lack of interest in industry is because few have even the slightest idea of what is done in a chemical plant and how chemists are woven into operations.

To a large extent, the chemical industry is concerned with making stuff. So perhaps it is only natural that most academic chemists (in my limited sample set) aren’t that keen on anything greater than a superficial view of the manufacturing world. I understand this and acknowledge reality. But it is a shame that institutional inertia is so large in magnitude in this. Chemical industry needs chemists of all sorts who are willing to help rebuild and sustain manufacturing in North America. We need startups with cutting edge technology, but we also need companies who are able to produce the fine chemical items of commerce. Have you tried to find a company willing and able to do bromination in the USA lately? A great deal of small molecule manufacture has moved offshore.

Offshoring of chemical manufacturing was not led by chemists. It was conceived of by spreadsheeting MBAs, C-suite engineers and boards of directors. It has been a cost saving measure that mathematically made sense on spreadsheets and PowerPoint slide decks. The capital costs of expansion of capacity could be borne by others in exchange for supply contracts. There is nothing mathematically wrong with this idea. Afterall, corporate officers have a fiduciary responsibility to their shareholders. Allowing profit opportunities to pass by is not the way to climb the corporate ladder.

We have become dependent on foreign suppliers in key areas who have control over our raw material supply. Part of control is having manufacturing capacity and closer access to basic feedstocks.

The gap between academia and industry is mainly cultural. But it is a big gap that may not be surmountable, and I’m not sure that the parties want to mix. But, I’ll keep trying.