Th’ Gaussling, traveling with a 3-van convoy of local geologists, participated in a field trip on May 22, 2010. The purpose of the trip was to get an appreciation of the kinds of faults to be found in and around the IRSZ and get some insight into the phenomena of faulting. The trip was organized by the Colorado Scientific Society, an earth science oriented organization. This was my second field trip with CSS.

GPS coordinates and elevations were acquired with a Garmin eTrex handheld receiver. Waypoints (WP’s) are just the latitude and longitude of physical locations of interest. Elevations generally aren’t required to find the formations, but are provided as a matter of general interest. The photographs are my own and if copied, I would appreciate a citation and/or link.

The trip leader was Jonathan S. Caine, a USGS research geologist who has done more than a bit of work relating fault and fracture networks and fluid flow in the earths crust. A feature called the Idaho Springs-Ralston Shear Zone (IRSZ) was part of the topic of this trip. As Caine says in the abstract on the previous link, the IRSZ is thought to be a persistant weakness in the continental crust. There is interest in the relationship between the IRSZ and the Colorado Mineral Belt.

WP003- N 39° 44.700′, W 105° 17.485′ elevation 6266′.

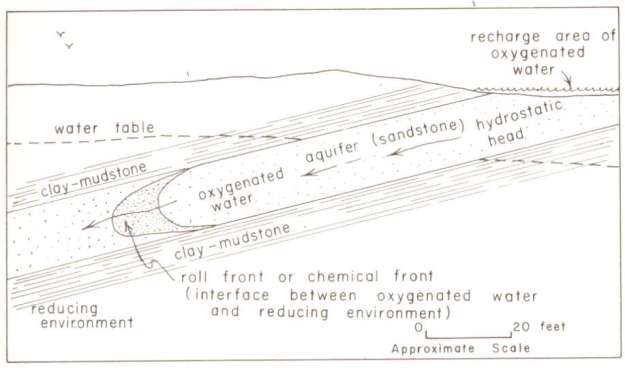

The Junction Ranch fault which had an exposure at waypoint 003 was an example of a fault in a formation that has seen considerable hydrothermal alteration. The orange iron stains on the rock are a clue that fluid transport of minerals has taken place. Calcite veins within the foliated clay filling the fault are an indication that the clay was deposited first. There is no evidence, however, that the fault predates the hydrothermal alteration.

In a roadcut along the Central City Parkway is an exposure of a brittle fault at location WP005- N 39° 44.990′, W 105° 28.233′, elevation 7571′.

The formation exposed at WP005 was part of a very old structure with multiple faults and igneous intrusions. In the photo above, the edge of the fault is enhanced with a black line drawn in during editing. The surface above the black line is an example of a slickenside, or one surface of the fault. Some members of the trip said they could see slickenlines, but they are so subtle that it is hard to be certain. A large igneous intrusion 100 m away showed signs of dislocation, presumably due to a fault. Boudins were observed at this location and are shown in the photo below.

We visited the location of a fault in Coal Creek Canyon. This is a NNW trending distributed deformation zone which is part of the Boulder Batholith. This location is designated WP008- N 39° 54.268′, N 105° 20.795′, elevation 7771′.

This fault was discovered filled with clay and dips 35 to 45 degrees. It was further exposed by excavation by Caine and another geologist. Again, the approximate boundary of the fault was enhanced with black lines in editing. There was considerable alteration of the rock on the hanging face side of the fault with iron staining associated with hydrothermal alteration.

We visited a ductile shear zone with suspected mylonite features. It was located at WP007- N 39° 51.026′, N 105° 21.155′, elevation 7634. Mylonite zones are evidence of ductile shear in response to a stress field. Near the mylonite zone was a fault with exposed slickensides. While faulting and ductile deformation may seem incompatible, it should be remembered that over time many kinds of phenomena can be overprinted on the rock formations. Rock may deform in a ductile manner and sometime later undergo brittle fracture.

The field trip leader was very enthusiastic and because of his background, was able to provide many important insights into the local geology. It was a very worthwhile day in the mountains.