I couldn’t resist a sarcastic allusion to post-modernism, whatever the hell that is. What could possibly be under such a bullshit heading? Well, all of my tramping around chemical plants from Europe, Russia, North America, and Asia as well as local mines and mills keeps leading me to an interesting question. Exactly who is being served in the current course of chemistry education? Is it reasonable that everyone coming out of a ACS certified degree program in chemistry is on a scholar track by default? Since I have been in both worlds, this issue of chemistry as a lifetime adventure is never far from my mind.

What are we doing to serve areas outside of the glamor fields of biochemistry and pharmaceuticals? There are thriving industries out there that are not biochemically or pharmaceutically oriented. There is a large and global polymer industry as well as CVD, fuels, silanes, catalysts, diverse additives industries, food chemistry, flavors & fragrances, rubber, paints & pigments, and specialty chemicals. There are highly locallized programs that serve localized demand. But what if you live away from an area with polymer plants? How do you get polymer training? How do you even know if polymer chemistry is what you have been looking for?

Colleges and universities can’t offer everything. They attract faculty who are specialists in areas of topical interest at the time of hire. They try to set up shop and gather a research group in their specialty if funding comes through. Otherwise, they teach X contact hours in one of the 4 pillars of chemistry- Physical, inorganic, organic, and analytical chemistry- and offer the odd upper level class in an area of interest.

Chances are that you’ll find more opportunities to learn polymer chemistry as an undergraduate in Akron, OH, than in Idaho or New Mexico. Local strengths may be reflected in local chemistry departments. But chances are that in most schools you’ll find faculty who joined after a post-doc or from another teaching appointment. This is how the academy gets inbred. The hiring of pure scholars is inevitable and traditional. But what happens is that the academy gets isolated from the external world and focused on enthusiasms that may serve civilization in distant ways if at all. The question of accountability is dismissed with a sniff and a wave of the hand of academic freedom. Engineering departments avoid this because they are in constant need of real problems to solve. Most importantly, though, engineers understand the concept of scarcity in economics. Chemists will dismiss it as a non-observable.

One often finds that disconnects are bridged by other disciplines because chemistry is so narrowly focused academically. It would be a good thing for industry if more degreed chemists found their way into production environments. I visited a pharmaceutical plant in Taiwan whose production operators were all chemical engineers. Management decided that they required this level of education. But, why didn’t they choose chemists? Could it be that they assumed that engineers were more mechanically oriented and economically savvy?

Gold mines will hire an analyst to do assays, but metallurgists to develop extraction and processing. Are there many inorganic chemistry programs with a mining orientation? Can inorganikkers step into raw material extraction from a BA/BS program or is that left to mining engineers?

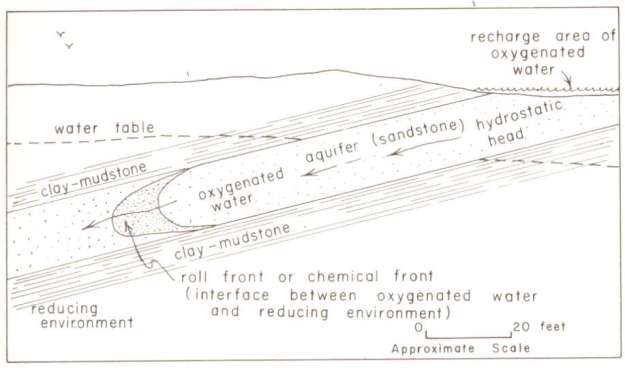

In my exploration I am beginning to see a few patterns that stand out. One is the virtual abdication of US mining operations to foreign companies. If you look at uranium or gold, there are substantial US mining claims held by organizations from Australia, South Africa, and Canada.

So, what if? What if a few college chemistry departments offered a course wherein students learned to extract useful materials from the earth? What if students were presented with a pile of rock and debris and told to pull out some iron or zinc or copper or borax or whatever value may happen to be in the mineral?

What if?? Well, that means that chemistry department faculty would have to be competent to offer such an experience. It also means that there must be a shop and some kilo-scale equipment to handle comminution, leaching, flotation, and calcining/roasting. It’s messy and noisy and the sort of thing that the princes of the academy (Deans) hate.

What could be had from such an experience? First, some hours spent swinging a hammer in the crushing process might be a good thing for students. It would give them a chance to consider the issues associated with the extraction of value from minerals. Secondly, it would inevitably lead to more talent funneling into areas that have suffered from a lack of chemical innovation. Third, it might have the effect of igniting a bit more interest in this necessary industry by American investors. The effect of our de-industrialization of the past few generations has been the wind-down of the American metals extraction industry (coal excluded).

If you doubt the effect on future technologies of our present state of partial de-industrialization, look into the supplies of critical elements like indium, neodymium, cobalt, rhodium, platinum, and lithium. Ask yourself why China has been dumping torrents of money into the mineral rich countries of Africa.

I can say from experience that some of the most useful individuals in a chemical company can be the people who are just as much at home in a shop as in a lab. People with mechanical aptitude and the ability to use shop tools are important players. Having a chemistry degree gives them the ability to work closely with engineers to keep unique process equipment up and running efficiently.

Whatever else we do, and despite protestations from the linear thinkers in the HR department, we need to encourage tinkerers and polymaths.

This kind of experience doesn’t have to be for everyone. God knows we don’t want to inconvenience Grandfather Merck’s or Auntie Lilly’s pill factories. Biochemistry students wouldn’t have to take time away from their lovely gels and analytical students could take a pass lest their slender digits become soiled. Some students are tender shoots who will never have intimate knowledge of how to bring a 1000 gallon reactor full of reactants to reflux, or how to deal with 20 kg of BuLi contaminated filter cake. But I hasten to point out that there are many students with such a future before them and their BA/BS degree in chemistry provides a weak background for industrial life.

A good bit of the world outside the classroom is concerned with making stuff. I think we need to return to basics and examine the supply chain of elements and feedstocks that we have developed a dependence upon. American industry needs to reinvest in operations in this country and other countries, just like the Canadians, South Africans, and Australians have. And academia should rethink the mission of college chemistry in relation to the needs of the world, rather than clinging to the aesthetic of a familiar curriculum or to the groupthink promulgated by rockstar research groups. We need scholars. But we also need field chemists to solve problems in order to make things happen.