Ask yourself this- will your descendants in the year 2125 share in the creature comforts coming from the extravagant consumption of resources that we presently enjoy? Shouldn’t the concept of “sustainability” include the needs of 4-5 generations down the line?

The word ‘sustainability’ is used in several contexts and in contemporary use remains a fuzzy concept with few sharp edges. In this post I will refer to the sustainability of raw materials, fully recognizing that it covers numerous aspects of civilization.

There are wants and there are needs. For the lucky among us in 21st century developed nations, our needs are more than satisfied leaving surplus income to satisfy many of our wants. Will our descendants a century from now even have enough resources to meet their needs after our historical wanton and extravagant consumption of resources dating to the beginning of the industrial age? Our technology stemming from the earth’s economically attainable resources has done much to soften the jagged edges of nature’s continual attempts to kill us. After each wave of nature’s threats to life itself, survivors get back up only to face yet more natural disasters, starvation and disease. This is where someone usually offers the phrase “survival of the fittest”, though I would add ” … and the luckiest”.

What will descendants in 100 or 200 years require to fend off the harshness of nature and our fellow man? Pharmaceuticals? Medical science? Fuels for heat and transportation? Will citizens in the 22nd century have enough helium for the operation of magnetic resonance imagers or quantum computers? Will there be enough economic raw materials for batteries? Will there be operable infrastructure for electric power generation and distribution? Lots of questions that are easy to ask but hard to answer because it requires predicting the future.

Come to think about it, does anyone worry this far in advance? The tiny piece of the future called “next year” is as much as most of us can manage.

Humans would do well to remember that a great many of the articles that we rely on are manufactured goods, such as: automobiles, aerospace-anything, pharmaceuticals, oil & gas, metals, glass, synthetic polymers (i.e., polyethylene, polypropylene, PVC, polystyrene etc.), medical technology and electrical devices of all sorts. Each of these categories split off into subcategories all the way back to a farm or a mine. And let’s remember that both mining and farming are both reliant on big, expensive machinery and lots of water.

The point is that nearly everything we have come to rely on sits at the super apex of many foundational apex technologies.

Each of the contributing technologies holding up any given apex technology were new and wondrous at one time. Think of a modern multicore microprocessor chip. Follow the chip’s raw materials back to the mines and oil & gas wells where the raw materials originated. Once you’ve done that, consider all of the people and inputs necessary in each step getting from the mine to the assembly of a working microprocessor. Each device, intermediate component or refined substance is at or near the apex of some other technology pyramid. To keep moving forward, people need to connect each apex technology input in a way to get to their own apex endpoint.

We mustn’t forget all of the machinery and components, energy to power them, transportation and trained personnel needed to manufacture any given widget. Skilled hands must be found to make everything work.

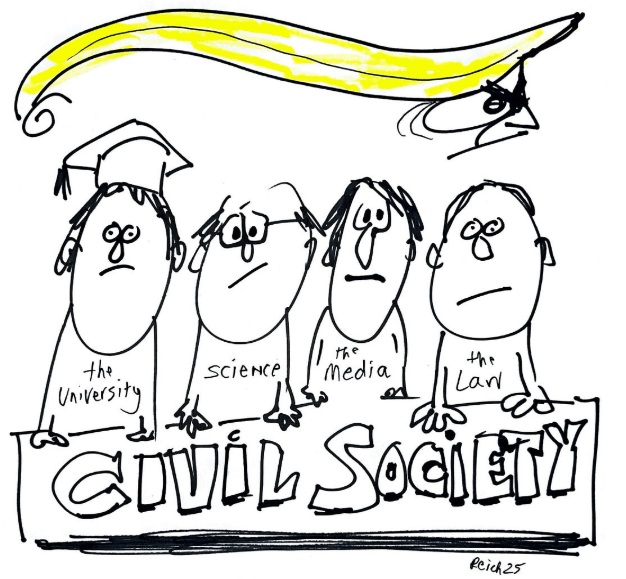

A given technology using manufactured goods is a house of cards kept upright by constant attention, maintenance, quality control and assurance, continuous improvement and hard work by sometimes educated and trained people. Then, there is a stable society with institutions, regulations and a justice system that must support the population. The technology driving our lifestyles does not derive from sole proprietor workshops in a corrugated iron Quonset building along the rail spur east of town. The highly advanced technology that is driving economic growth and the comfortable lives we enjoy comes from investors and factories and international commerce. A great many products we are dependent on like cell phones are affordable only because of the economies of large-scale production.

So, what is the point of this? Sustainability must also include some level of throttle back in consumption without upsetting the apple cart.

A plug for climate change

For a moment, let’s step away from the notion that the atmosphere is so vast that we cannot possibly budge it into a runaway warming trend. The atmosphere covers the entire surface of the planet with all of its nooks and crannies, but its depth is not correspondingly large. In fact, the earth’s atmosphere is rather thin.

At 18,000 feet the atmospheric pressure drops to half that at sea level. The 500 millibar level varies a bit but is generally near this altitude. This means that half of the molecules in the atmosphere are at or below 18,000 feet. This altitude, the 500 millibar line, isn’t so far away from the surface. From the summits if the 58 Fourteeners in Colorado, it is only 4000 ft up. That is less than a mile. The Andes and the Himalayan mountains easily pierce the 500 millibar line.

Our breathable, inhabitable atmosphere is actually quite thin. The Earth’s atmosphere tapers off into the vacuum of space over say 100 km, the Kármán line. Kármán calculated that 100 km is the altitude at which an aircraft could no longer achieve enough lift to remain flying. While this is more of an aerodynamics based altitude than a physical boundary between the atmosphere and space, the bulk of the atmosphere is well below this altitude. With the shallow depth of the atmosphere in mind, perhaps it seems more plausible that humans could adversely affect the atmosphere.

The lowest distinct layer of the atmosphere is the troposphere beginning as the planetary boundary layer. This is where most weather happens. In the lower troposphere, the atmospheric temperature begins to drop by 9.8 °C per kilometer or 5.8 oF per 1000 ft of altitude. This is called the dry adiabatic lapse rate. (With increasing altitude the temperature gradient decreases to about 2 oC per kilometer at ~30,000 ft in the mid-latitudes where the tropopause is found. The tropopause is where the lapse rate reaches a minimum then the temperature remains relatively constant with altitude. This is the stratosphere.)

Over the last 200 years in some parts of the world, advances in medicine, electrical devices, motor vehicles, aerospace, nuclear energy, agriculture and warfare have contributed to what we both enjoy and despise in contemporary civilization. The evolving mastery of energy, chemistry and machines has replaced a great deal of sudden death, suffering and drudgery that was “normal” affording a longer, healthier lives free of many of the harmful and selective pressures of nature. Let’s be clear though, continuous progress relieving people of drudgery can also mean that they may be involuntarily removed from their livelihoods.

It is quintessentially American to sing high praises to capitalism. It is even regarded as an essential element of patriotism by many. On the interwebs capitalism is defined as below-

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit.

As I began this post I was going to cynically suggest that capitalism is like a penis- has no brain. It only knows that it wants more. Well, wanting and acquiring more are brain functions, after all. Many questions stand out, but I’m asking this one today. How fully should essential resources be subject to raw capital markets? It has been said half in jest that capitalism is the worst economic system around, except for all of the others.

I begin with the assumption that it is wise that certain resources should be conserved. Should it necessarily be that a laissez faire approach be the highest and only path available? Must it necessarily be that, for the greater good, access to essential resources be controlled by those with the greatest wealth? And, who says that “the greater good” is everybody’s problem? People are naturally acquisitive- some much more than others. People naturally seek control of what they perceive as valuable. These attributes are part of what makes up greed.

Obvious stuff, right?

The narrow point I’d like to suggest is that laissez faire may not be fundamentally equipped to plan for the conservation and wise allocation of certain resources, at least as it is currently practiced in the US. Businesses can conserve scarce resources if they want by choosing and staying with high prices, thereby reducing demand and consumption. However, conservation is not in the DNA of business leaders in general. The long-held metrics of good business leadership rest on the pillars of growth in market share and margins. Profitable growth is an important indicator of successful management and a key performance indicator for management.

First, a broader adoption of resource conservation ideals is necessary. Previous generations have indeed practiced it, with the U.S. national park system serving as a notable example. However, the scarcity of elements like Helium, Neodymium, Dysprosium, Antimony and Indium, which are vital to industry and modern life, this raises concerns. The reliance of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) operations on liquid helium for their superconducting magnets poses the question of whether such critical resources should be subject to the whims of unregulated laissez-faire capitalism. While some MRI operators utilize helium recovery systems, not all do, leading to further debate on whether the use of helium for frivolity should continue, given its wasteful nature.

Ever since the European settlement of North America began, settlers have been staking off claims for all sorts of natural resources. Crop farmland, minerals, land for grazing, rights to water, oil and gas, patents, etc. Farmers in America as a rule care about conserving the viability of their topsoil and have in the past acted to stabilize it. But, agribusiness keeps making products available to maximize crop yields, forcing farmers to walk a narrower line with soil conservation. Soil amendments can be precisely formulated with micronutrients, nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers to reconstitute the soil to provide for higher yields. Herbicides and pesticides are designed to control a wide variety of weeds, insect and nematode pests. Equipment manufacturers have pitched in with efficient, though expensive, machinery to help extract the last possible dollars’ worth of yield. Still other improvements are in the form of genetically modified organism (GMO) crops that have desirable traits allowing them to withstand herbicides (e.g., Roundup), drought or a variety of insect, bacterial, or fungal blights. The wrench in the gears here is that the merits of GMO crops have not been universally accepted.

Livestock production is an advanced technology using detailed knowledge of animal biology. It includes animal husbandry, nutrition, medicines, meat production, wool, dairy, gelatin, fats and oils, and pet food production. There has been no small amount of pushback on GMO-based foods in these areas, though. I don’t follow this in detail, so I won’t comment on GMO.

The point of the above paragraphs is to highlight a particular trait of modern humans- we are demons for maximizing profits. It comes to us as naturally as falling down. And maximizing profits usually means that we maximize throughput and sales with ever greater economies of scale. Industry not only scales to meet current demand, but scales to meet projected future demand.

Extracting a mineral resource to its exhaustion has been prevalent in history. The question is, is it inevitable or can or should it be throttled back? But who will do that in the face of market demand?

Essentially everyone will likely have descendants living 100 years from now. Won’t they want the rich spread of comforts and consumer goods that we enjoy today? Today we are producing consumer goods that are not made for efficient economic resource recovery. Batteries of all sorts are complex in their construction and composition. Spent batteries may have residual energy left in them and have chemically hazardous components like lithium metal. New sources of lithium are opening up in various places in the world, but it is still a nonrenewable and scarce resource. This applies to cobalt as well.

Helium is another nonrenewable and scarce resource that in the US comes from a select few enriched natural gas wells. At present we have an ever-increasing volume of liquid helium consumption in superconducting magnets across the country that need to remain topped off. This helium is used in all of the many superconducting magnetic resonance imagers (MRI) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers in operation worldwide. Quantum computing will also consume considerable liquid helium as it scales up since temperatures below the helium boiling point of 4.22 Kelvin are required.

As suggested above, today’s MR imagers can be equipped with helium boil off recovery devices that recondense helium venting out of the cryostat and direct it back into a reservoir. One company claims that their cold head condensers are so efficient that users do not even have to top off with helium for 7-10 years. That seems a bit fantastic, but that has been claimed. Helium recovery is a good thing. Hopefully it is affordable for most consumers of MRI liquid helium.

In the history of mining in the US and elsewhere, it has been the practice of mine owners to maximize the “recovery” of run-of-mill product when prices are high. Recovery always proceeds to the exhaustion of the economical ore or the exhaustion of financial backing of the mining company. Uneconomical ore will remain in the ground, possibly for recovery when prices are more favorable. It is much the same for oil and gas. As with everything, investors want to get in and get out quickly with the maximum return and minimum risk. They don’t want their investment dollars to sit in the ground waiting for the distant future in order to satisfy some pointy headed futurist and their concern for future generations.

It is not normally in the nature of for-profit corporate C-suite executives to aim for resource conservation. People answerable to a board of directors have a fiduciary responsibility to maximize wealth generation for the shareholders. The world of industry is the world of growth. The world of “let’s make enough to get by” is not the world of people who rise to the C-suite. Unfortunate perhaps, but true.

What is needed in today’s world is the ability to conserve resources for our descendants. It requires caring for the future along with a good deal of self-control. Conservation means recycling and reduced consumption of goods. But it also means tempering expectations for extreme wealth generation, especially for those who aim for large scale production. While large scale production yields the economies of scale, it nevertheless means large scale consumption as well. In reality, this is contrary to the way most capitalism is currently practiced around the world.

Sustainability

The libertarian ideal of applying market control to everything is alleged to be sustainable because in appealing to everyone’s self-interest, future economic security is in everyone’s interest. If high consumption of scarce resources is not in our long-term self-interest, then will the market find a way to prolong it? As prices rise in response to scarcity, consumption should drop. ECON-101 right? Well, what isn’t mentioned is that it’s today’s self-interest. What about the availability of scarce resources for future generations? Will the market provide for that?

What does “sustainability” really mean? Does it mean that today’s high consumption is sustained, or does it mean resource conservation by reduced consumption?

Is the goal of energy sustainability to maintain the present cost of consumption but through alternative means? Reduced consumption will occur when prices get high enough. As the cost of necessities rises, the cash available for the discretionary articles will dry up. How much of the economy is built on non-essential, discretionary goods and services? The question is, does diminished consumption have to be an economic hard landing or can it be softened a bit?

Where does technological triumphalism take us?

The generation and mastery of electric current has been one of the most consequential triumphs of human ingenuity of all time. It is hard to find manufactured goods that have not been touched by electric power somewhere in the long path from raw materials to finished article. As of the date of this writing, we are already down the timeline by many decades as far as the R&D into alternative electrification. What we are faced with is the need to continue rapid and large scaling-up of renewable electric power generation, transmission and storage for the anticipated growth in renewable electric power consumption for electric vehicles.

Our technological triumphalism has taken us to where we are today. The conveniences of contemporary life are noticed by every succeeding generation who, naturally, want it to continue. This necessitates that the whole production and transportation apparatus for goods and services already in place must continue. We have both efficient and inefficient processes in operation, so there is still room for more triumph. But eventually resources will become thin and scarcity of strategic minerals becomes rate limiting. Economies may or may not shift to bypass all scarcity of particular articles.

Perhaps a transition from technological triumphalism to minimalist triumphalism could take place. The main barrier there is to figure out how to make reduced consumption profitable. Yes, operate by a low volume, high margin business model. That already works for Rolls Royce, but what about cell phones and sofas?

Something else that stymies attempts at reduced consumption is price elasticity. This is where an increase in price fails to result in a drop in demand. Necessary or highly desirable goods and services may not drop in demand if the price increases at least to some level. As with the price of gasoline, people will grumble endlessly about gas prices as they stand there filling their tanks with expensive gasoline or diesel. Conservation of resources has to overcome the phenomenon of price elasticity in order to make a dent without shortages.

A meaningful and greater conservation of resources will require that people be satisfied with lesser quantities of many things. In history, people have faced a greatly diminished supply of many things, but not by choice. Economic depression, war and famine have imposed reduced consumption on whole populations and often for decades. When the restriction is released, people naturally return to consumption as high as they can afford.

The technological triumph reflex of civilization has allowed us to paint ourselves into a resource scarcity corner.

I’d like to believe that humanity could stave off the enviable conflict that would spark from numerous critical resource shortages, but I doubt the people and nations of the world can do it.