[Note: Formerly named “PhD Chemists are freaks!!,” this essay has been renamed to better match the content.]

Preamble: Yes, yes, yes. Obviously, I’m aware that my experience in no way represents the careers of nearly all chemists. As usual, I drift into adjacent chemistry topics. Get your hands away from the keyboard and just read.

Bud (a pseudonym), a PhD chemist consultant and coworker, claimed that people with the exalted PhD degree were freaks of nature. Bud opined “Just look at us! Who goes to school for as long as we did and then ends up in a place like this?” I didn’t add at that moment that between a BA, PhD, 2-year postdoc and a stint in the professor trade, I was in academics for 16 years and walked away from it. Just then I couldn’t defend how smart it might have been to tread down this path only to end up in an old office trailer where we were sitting at that moment.

Bud used to argue that PhDs in general were freaks in society. Only a small fraction of undergrads will go on to grad school and fewer still complete a PhD program. The fraction is smaller yet in the general population.

In science you need a PhD in order to have even a hope of leading an R&D project, technical C-Suite corporate position, institute or professorship. The degree isn’t intended to resemble a trade, but rather to be a highly educated scholar and a subject matter expert with good communication skills and a sharp mind. If one is investigating for new phenomena, an intimate knowledge of known phenomena is needed to discriminate a finding. No awards for rediscovery.

Bud retired from a career at a big chemical corporation only to jump back into the hairball as a sales consultant for us in his retirement. I was a couple of years into what would be my major career “choice” and was managing the sales & marketing department then. Somehow, I had stumbled into the business side.

Our other sales consultant, the “Great Gondini”, retired from a photocopier company as a PhD chemist developing magnetic media, charge transfer agents and other xerographic-related materials. From his soapbox he advised us to-

Avoid being a chemist in a non-chemical-oriented company.

It’s not that non-chemical-company chemists couldn’t rise up the career ladder, but being in a niche subspecialty at a company that produced photocopiers was not the way to grow your career in chemistry. Often such a chemist may be the only chemistry PhD on site and is likely to suffer from professional isolation. Experience with project execution on time and on budget is a great way to rise in a company. Engineers frequently rise to top level positions because they understand technology AND quantitative economics.

The universe for a chemist is 2-dimensional- space vs time. For an engineer, the universe is 3-dimensional- space vs time vs costs. Who would you appoint to manage construction, install new process equipment or run your business?

I knew 2 BS/BA level chemists and 1 PhD level chemist who obtained MBAs. Their careers leapt into higher gear with their move to the business side. In business it is important for at least someone to understand how finance works in addition to the technology. Even graduating with a business minor might be helpful but not as much as an MBA. I got an A in ECON 101 but only I cared. Education in basic accounting is very helpful on the business side.

As I see it, some realities of being in industrial chemistry R&D.

In my organic-synthesis-oriented research group in grad school, the big dream was to get an R&D job in pharma R&D. Cool medicinal chemistry and a chance to help to cure disease for the benefit of mankind. It is an honorable and, if I may be permitted to say so, prestigious career as a pharmaceutical scientist. At least in the world of chemistry.

Since then, more than a few in my grad school cohort had been laid off by the pharma companies or joined another. A few have been laid off 3 times from what they believed were secure slots. Pharma companies, like most others, aren’t run by chemists for the most part. Quarterly EBITDA is a major driver for the board of directors. The C-Suites are packed with corporate and patent lawyers, retired CEOs, MBAs, Md/PhDs, CPA finance people and perhaps a PhD chemist heading up the R&D operation as a Director or Vice-President.

After all, the most important reaction in all of chemistry is transforming chemicals into money.

After my academic career and my short rotation through the polymer world, I ended up for 6 years in chemical sales and marketing which was limited by my personal geographic requirement of living in the mountainous western US. As my opinion of the pharma business matured, I discovered that, as a raw material vendor, to be ever so careful with pharma customer promises and purchase orders. Not because they are liars, but because many felt free to cancel orders even after bulk raw materials arrived and after our R&D effort to meet specs. Their interest in us was based on using our low bid to leverage another supplier on price. This is common actually and I have done it myself. They waved future business in our faces knowing that, probably, they would never send receive an invoice. Still, not unheard of. But the hassle and our wasted R&D and opportunity costs were especially galling. But we were a spot supplier and susceptible to such disruption. My company didn’t like to sign contracts at that time, so we always took the risk on spot buys. Spot sales gave us manufacturing flexibility as a custom chemical producer, but at the expense of uncertainty. Later, attracted by the same sweet songs of Lorali that led hapless sailors into the rocks, we would repeat this fool’s errand once more.

Off-topic advice

Always be certain that the qualification sample you ship to a potential customer is NOT the purest sample that R&D can produce. It must be representative of what the scaled-up process can deliver. Otherwise, you may be stuck having to reproduce lab results at larger scale which can be very problematic. They will often spec-out your product at the purity of the sample. Then you have to live with it or decline the business.

Back to our regularly scheduled programming

On one occasion a big pharma customer wanted a product delivered across the Atlantic to Ireland. Time and distance weren’t the issue, though. It would equilibrate and precipitate below about 15 oC on the transatlantic voyage, so we bought heated shipping containers and installed them in Ireland on a site that wasn’t afraid of the W (indicating a water-reactive hazard) on the hazard labels or the safety data sheets. Scheduling heated transport could be sketchy in fall, winter and spring because most were booked for shipping fruits and vegetables. So, a month into the campaign and after an encouraging site visit by two of us sales guys (Tipperary isn’t so far after all), I received a call saying that they had changed their process (!?) and that a competing European supplier was chosen to ship directly from the continent on demand and without the (our) expense of staging heated storage. Once a pharma company writes in each raw material into their drug filing, changing suppliers or a change in specifications requires the heavens to open up and thunder “make it so.” In the end, they reimbursed us for raw material costs only. &#$@%*&^!! This would happen again later but with a more difficult product to produce.

My early career path led me away from the fabulous pharma world and into undergraduate teaching, initially. The other group members achieved their goals of a pharma R&D position. While I spent the next 6 years in academia one way or another, my grad school colleagues were drawing big salaries with 401(k)s in well-equipped labs, but in locations on the US East Coast, Gulf Coast or Midwest- regions that I would never consider moving to. In the end, most buoyantly bobbled up the career ladder to become directors and vice-presidents of R&D or technology as their final positions. No disrespect, just envy.

Climbing the Career Ladder

A few talented chemist colleagues from grad school climbed up the corporate ladder without business training, learning what they need on the job. Most others, though, remained in the tech end. The reality of being a scientist in industry is that upward mobility in a large corporation very much depends on your improvements in job performance, profitability, volume or especially the successful execution of a capital project. But capital projects are normally given to engineers because they are trained to deal with the cost of the equipment and in the cost of operation.

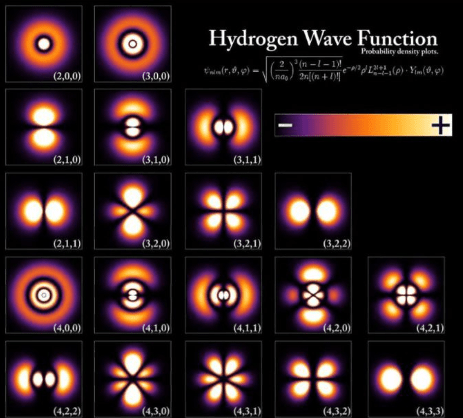

In my experience, a BA/BS, MA/MS or PhD chemist can usually retire as a senior bench chemist, analyst or lab project leader managing bench chemists. If you enjoy lab work, this is it. By retirement you’ve already topped out on the salary scale and have put away a fair sum in the 401 (k). It is a good life for a great many. But for myself, my interest in bench work dropped from hot to tepid after my 2-year postdoc. I got into molecular modeling and dynamics as a postdoc and actually answered a vexing question about kinetic vs thermodynamic control in a reaction that gave contradictory results. Even got a JACS paper out of it. It was fascinating stuff, but it made me look away from straight synthetic chemistry long enough to appreciate computational and physical chemistry.

As a postdoc I used AMBER and SPARTAN, I did molecular dynamics and molecular mechanics to make a stab what was possibly the global minimum strain energy. Ring strain calculations were used as a coarse screen for potential comonomers for the ring-opening polymerization (OP) reaction we were hoping to commercialize. The homopolymer was amber colored, brittle and rattled when handled as film. The comonomer idea based on the notion that the homopolymer contained too much crystallinity. The glass transition temperature needed to be at least below room temp. Suppressing the crystallinity and retaining certain key properties along with biodegradability was crucial. Even worse, the proposed comonomer must participate in reactive extrusion with the original monomer and be available in commercial quantities at a low cost. Finally, the copolymer needed to be water white. The color spec was difficult to achieve.

Final Comments:

My comments in this essay are based on personal experiences in my world. Your world is almost certainly quite different.

I haven’t mentioned analytical chemists because their world continues to be overtaken by automated instrumentation that will calculate the results and put together a report for you. Sampling and wet chemistry are still hands-on operations as far as I can tell. But this is taken as a challenge to instrument makers who will try to engineer around the hands-on requirement to provide something that can be automated. In my world I see more employee turnover with BA/BS analytical chemists than with organic R&D chemists.

As far as employee turnover goes, analysts are under continuous pressure to produce results so that production can proceed or to get product out the door. With hundreds of raw mats, intermediates, and final products, each with their own standard test methods and specs, I certainly wouldn’t last long as an analytical chemist.