This post is an update of a post I wrote on Mole-Day of 2011. It is a brain dump that summarizes much of what I’ve learned about dealing with potentially explosive chemicals in the manufacturing environment. Very few chemists actually have to deal with explosive chemicals in their work activities. It is actually quite uncommon. No doubt some important considerations have been left out and for that I apologize.

The Prime Directive: If you choose to bring in or make a chemical substance in your facility, you must develop in-house expertise in the safe handling and use of that substance. Do not expect to rely on outside expertise for it’s safe use. Always strive to build in-house expertise in regard to chemical properties and safety- never farm this out to consultants. This includes proper engineering and broad knowledge of reactive chemical hazards.

Safety has a substantial psychological component. You can build into a chemical manufacturing process extensive engineering and administrative controls for safe operation. These layers of control are concrete and definable. What is fuzzy, however, is the matter of how people behave. In particular, I’m thinking of getting people to behave in a particular way over the long haul. Keeping people operating safely over long periods of time where no adverse events happen poses special problems. Especially in regard to low frequency, high consequence events. Cutting corners and improper use of PPE is not uncommon and should be expected. Something expected can be watched for continuously.

In safety training I mention that handling a hazardous material is like handling a rattle snake. You have to exercise the due caution every single time you pick up that snake. You do not accumulate and bank safety credits for previous safe handling. Everybody understands this already at some level. But the possibility of drift in safety practice over time needs to be emphasized.

The best strategy I know of besides complete process automation is recurrent safety training along with vigilant management. Successful safety management requires proper supervision by alert supervisors. Management by walking around helps with this. Well written process instructions that anticipate practical problems are essential. Holding people accountable for following Standard Operating Procedures is critical. Working conditions conducive to focus are always good. Operational rotation with may be helpful.

In chemical safety, the biggest worry is typically the potential for an explosion. What should you do if a raw material or product in a process may be explosive or has explosive features on the molecule? Good question. First, someone in the R&D chain of command should have knowledge of the list of known explosophores. It’s not a big list. PhD chemists in R&D should know this anyway. Explosive molecules have certain chemical bonds that are weakest and are known as “trigger bonds“. It is thought that the rupture of these trigger bonds initiates explosive decomposition of the substance.

Just because a material has explosive properties does not automatically disqualify it for use. Azides and nitro compounds are used safely every day. But, to use a chemical safely you must accumulate some knowledge on the type and magnitude of stimulus that is required to give a hazardous release of energy.

For any given hazard, it is my personal policy to learn as much about the nature of the hazard at the chemical and bulk level as I can. I believe that it is important to know more about something than what is immediately called for. That is the difference between education and training. This is how you build expertise.

Some comments on the release of hazardous energy. Hazardous energy is that energy which, if released in an uncontrolled way, can result in harm to people or equipment. This energy may be stored in a compressed spring, a tank of compressed gas, the stable chemical bonds of a flammable material, the unstable chemical bonds of an explosive material, or as an explosive mixture of air and fuel. A good old fashioned pool fire is a release of hazardous energy as well. Radiant energy heating from a pool fire can easily and rapidly accelerate nearby materials past the ignition point. Good housekeeping goes a long way towards preventing the spread of fires.

Applying and accumulating energy in large quantities is common and actually necessary in many process activities. In chemical processing, heat energy may be applied to chemical reactions. Commonly, heat is released from chemical reactions at some level ranging from minimal to large. The rate of heat evolution in common chemical reactions can be simply and reliably managed by controlling the temperature or rate of addition of reactants where two reactants are necessary. However, reactions do not always evolve significant power output immediately on mixing of the reactants.

Induction periods are potentially dangerous and must be identified prior to scale up. The appearance of an exotherm very early in a feed operation is a good indication that the reaction has begun. However, a thermogram from a reaction calorimeter showing the temperature and power output (watts) versus the feed mass will indicate if the reaction is slow and accumulation of reagent (energy) is occurring. This can be teased out early by adding a small shot of reactant feed (a few %) and watching the power profile. The ideal profile is where the power output starts promptly, peaks and then promptly decays to baseline. This is a good indicator of the absence of accumulation. Generally, the kinetics are most favorable at the beginning of the reagent feed and taper off to zero as reactants are consumed. Some accumulation is usually tolerable from the heat load perspective. This is a good thing because a thermogram showing some accumulation could lead to an unnecessarily long feed time. A reaction calorimeter can give the peak wattage per kilogram of reaction mass. An engineer should be able to estimate the maximum controllable heat flux for a given reactor. Without being too specific, it is in the range of several tens of watts per kg of reaction mass according to one reference I know.

There are explosive materials and there are explosive conditions. If one places the components of the fire triangle into a confined space, what may have been simple flammability in open air is now the makings of an explosion. Explosive materials have two legs of the fire triangle built into the molecule- the oxidizer and the fuel separated by only nanometers. However, the composition of the explosive itself may not produce a balanced reduction/oxidation reaction. The oxygen balance is a easily calculated number that will indicate whether or not there is an excess or deficit of oxygen in an explosive substance. For example, ammonium nitrate has a 20 % excess of oxygen. Fuel oil can be added to bring the fuel/oxidizer ratio into redox balance. This mixture is referred to as ANFO.

In a chemical explosion, heat and increasing pressure can do PV work on the contents and containment. Minimally, the outcome will be an overpressure with perhaps the blowing of a rupture disk on a reactor. In another situation, the equipment may blow apart and send fragments flying away at high speed with an expanding fireball.

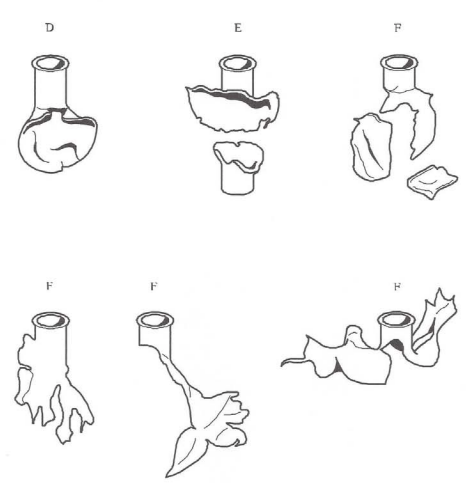

There is a particular type of explosive behavior called detonation. Detonation is a variety of explosive behavior that is characterized by the generation and propagation of a high velocity shock through a material. A shock is a high velocity compression wave which begins at the point of initiation and propagates throughout the bulk mass of explosive material. Interestingly, because it is a wave, it can be manipulated somewhat by reflection and refraction. This is the basis for explosive lensing and shaped charges. It is characteristic of detonations to produce shredded metal components. Detonations have a very large rate of pressure rise, dP/dt. The magnitude of dust explosions is commonly performed by a few commercial test labs out there. One of the important test results is the Kst value showing the magnitude of the explosive force.

Detonable materials may be subject to geometry constraints that limit the propagation of the shock. A cylinder of explosive material may or may not propagate a detonation wave depending on the diameter. Some materials are relatively insensitive to the shape and thickness. A film of nitroglycerin will easily propagate as will a slender filling of PETN in detonation cord. But these compounds are for munitions makers, not custom or fine chemical manufacturers. The point is that explosability and detonability is rather more complex than one might realize. Therefore, it is important to do a variety of tests on a material suspected of explosability. The type and magnitude of stimulus necessary to produce an explosion must be understood for safe handling and shipping.

A characteristic of detonable explosives is the ability to propagate a shock through the bulk of the explosive material. However, this ability may depend upon the geometry of the material, the shock velocity, and the purity of the explosive itself. There are other parameters as well. Marginally detonable materials may lose critical energy if the shape of the charge provides enough surface area for loss of energy.

Explosive substances have functional groups that are the locus of their explosibility. A functional group related to the initiation of explosive behavior, called an explosophore, is needed to give a molecule explosability. Obvious explosophores include azide, nitro, nitroesters, nitrate salts, perchlorates, fulminates, diazo compounds, peroxides, picrates and styphnates, and certain hydrazine moieties. Other explosophores include the hydroxylamino group. HOBt, a triazole analog of hydroxyamine, hydroxybenzotriazole, has injured people, destroyed reactors and caused serious damage to facilities. Anhydrous hydroxylamine has been the source of a few plant explosions as well. It is possible to run a process for years and never cross the line to runaway as was the case for these substances.

Let’s go back to the original question of this essay. What do you do if you find that a raw material or a product is explosive? The first thing to do is collect all available information on the properties of the substance. In a business organization, upper management must be engaged immediately since the handling of such materials involves the assumption of risk profiles beyond that expected.

At this point, an evaluation must be made in relation to the value of the product in your business model vs the magnitude of the risk. Dow’s Fire and Explosion Index is one place to start. This methodology attempts to quantify and weight the risks of a particular scenario. A range of numbers are possible and a ranking of risk magnitude can be obtained therein. It is then possible to compare the risk ranking to a risk policy schedule generated beforehand by management. The intent is to quantify the risk against a scale already settled upon for easier decision making. A problem with this approach is that it requires numerical values for risk which might be difficult to come by.

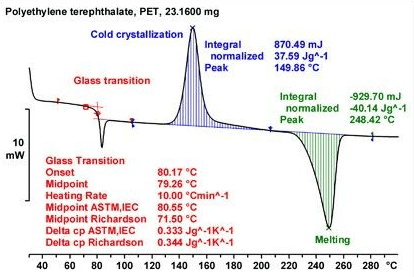

But even before such a risk ranking can be made, it is necessary to understand the type and magnitude of stimulus needed to elicit a release of hazardous energy. A good place to start is with a DSC thermogram and a TGA profile. These are easy and relatively inexpensive. A DSC thermogram will indicate onset temperature at a given temperature ramp rate and energy release data as a first pass. Low onset temperature and high energy release is least desirable. High onset temperature and/or low exothermicity is most desirable.

What is more difficult to come to a decision point on is the scenario where there is relatively high temperature onset and high exothermicity. Inevitably, the argument will be made that operating temperatures will be far below the onset temp and that a hazardous condition may be avoided by simply putting controls on processing temperatures. While there is some value to this, here is where we find that simple DSC data alone may be inadequate for validating safe operating conditions.

Onset temperatures are not inherent physical properties. Onset temperatures are kinetic epiphenomena that are dependent on the sensitivity of the instrument, sample quality, the Cp of both the sample and the crucible, and the rate of temperature rise. What may be needed once an indication of high energy release is indicated by the DSC is a determination of time to maximum rate (TMS). While this can be done with special techniques in the DSC (i.e., AKTS), TMR data may be calculated from 4 DSC scans at different rates, or it may be determined from Accelerated Rate Calorimetry, or ARC testing. Arc testing gives time, temp, and pressure profiles that DSC cannot give. ARC also gives an indication of non-classical liquid/vapour behavior that is useful. ARC testing can indicate the generation of non-condensable gases in the decomposition profile which is good to know.

Time to maximum rate is measured in time at a specified temperature. Many people consider that a TMR of 24 hours at the process temperature is a minimum threshold for operational safety. Others might advise 24 hours 50 or 100 C above the maximum operational temperature. If you contemplate using this parameter, it is critical to get testing from a professional lab for a time at a particular temperature. This kind of test will produce a formula that you can calculate TMR values at a given temperature. Bear in mind, however, that no outside safety consultant will tell you what you must do for liability reasons. You must develop enough in-house expertise to make this decision for yourself.

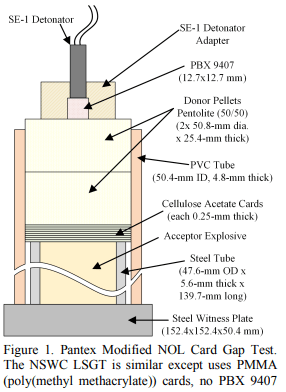

The standard tiered test protocol for DOT classification is a good place to start for acquiring data on explosive properties. Several companies do this testing and give ratings. There are levels of testing applied based on the result of what the lower series tests show. Series 1 and 2 are minimally what can be done to flesh out the effects of basic stimuli. What you get from the results of Series 1, 2, and 3 are a general indication of explosibilty and detonability, as well as sensitivity to impact and friction. In addition, tests for sensitivity to electric discharge and dust explosion parameters should be performed as well.

The card gap test, Konen test, and time-pressure test will give a good picture of explosive behavior. The Konen test indicates whether or not extreme heating can cause an explosion sufficient to fragment a container with a small hole in it.

BOM or BAM impact testing will indicate sensitivity to impact stimulus. Friction testing gives threshold data for friction sensitivity.

ESD sensitivity testing gives threshold data for visible effects of static discharge on the test material. Positive results include discoloration, smoking, flame, explosive report, etc.

Once the data is in hand, it is necessary to sift through it and make some business decisions. There is rarely a clear line on the ground to indicate what to do unless there is already a policy on decision making here. What testing results will indicate is what kind of stimulus is necessary to give a positive result with a particular test. It is up to your in-house experts and management to decide the likelihood of exposing the material to a particular stimulus. Will it be possible to engineer away the risk or diminish it to an acceptable level? The real question for the company is whether or not the risk of processing with the material is worth the reward. Everyone will have an opinion.

The key activity is to consider where in the process an unsafe stimulus may be applied to the material. If it is thermally sensitive in the range of heating utilities, then layers of protection guarding against overheating must be put in place. Layers of protection should include multiple engineering and administrative layers. Every layer is like a piece of Swiss cheese. The idea is to prevent the holes in the cheese from aligning.

If the material is impact or friction sensitive, then measures to guard against these stimuli must be put in place. For solids handling, this can be problematic. It might be that preparing the material as a solution is needed for minimum solids handling.

If the material is detonable, then all forms of stimulus must be guarded against unless you have specific knowledge that indicates otherwise. Furthermore, a safety study on storage should be performed. Segregation of explosable or detonable materials in storage will work towards decoupling of energy transfer during an incident. By segregating such materials, it is possible to minimize the adverse effects of fire and explosion to the rest of the facility.

With explosive materials, electrostatic safety is very important. All handling of explosable solids should involve provisions for the suppression of electrostatic charge generation and accumulation. A discharge of static energy in bulk solid material is a good way to initiate runaway decomposition of an energetic material. Unfortunately, some explosive substances may not require the oxygen leg of the fire triangle so, in this case, inerting with nitrogen won’t be preventative.

Safe practices involving energetic materials require an understanding the cause and effect of stimulus on the materials themselves. This is of necessity a data and knowledge driven activity. Handwaving arguments should also be suppressed in favor of data-driven analysis.