As I bumble and tumble through the chemical literature I frequently run into interesting chemicals and chemistry. Today’s moment of chemistry is with the “Wine Lactone”, so called because it is found in, well, wine. Interestingly it was first identified in koala urine. I saw that this was an opportunity also to dissect the chemical name of the Wine Lactone and perhaps answer questions that you didn’t know you had.

There are numerous forms of the wine lactone that have seemingly minor differences but have different odors. Some of the other “forms” are called stereoisomers and others positional isomers. The atomic composition is the same, but the atoms and their bonds are arranged in a slightly different way. It is not uncommon for these differences to result in a change to the odor or some other property.

The problem with chemical names (nomenclature) for people outside of chemistry is that they seem to be over-complicated polysyllabic tongue twisters with numbers and sometimes Greek letters that are impossible to pronounce or remember. Indeed, they are very often complex and seem to have a mysterious origin. This is where chemistry has strayed away from medieval naming “habits” and supplanted it with a systematic naming system that describes the exact atomic composition, how the atoms are connected and, if necessary, the particular shape in three dimensions.

For thoroughness I’ll point out the molecular formula style like CxHyNzOt where x y, z and t are variable numbers. Other elements were left out for convenient description here. Any organic molecule can be described by the numbers of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and other atoms present. While the molecular formula is an accurate representation and is necessary for calculating molecular weight, as a unique identifier it is not very useful. Any given polyatomic molecule may have more than one structure that fits the molecular formula.

There are several groups that have been influential in chemical databases and nomenclature around the world. German chemists were on top of this early on with the German language Beilstein database and system of nomenclature (1881) for organic substances, now maintained by Elsevier Information Systems in Frankfurt. For inorganic and organometallic substances, there is the Gmelin database (1817) which is maintained by Elsevier MDL.

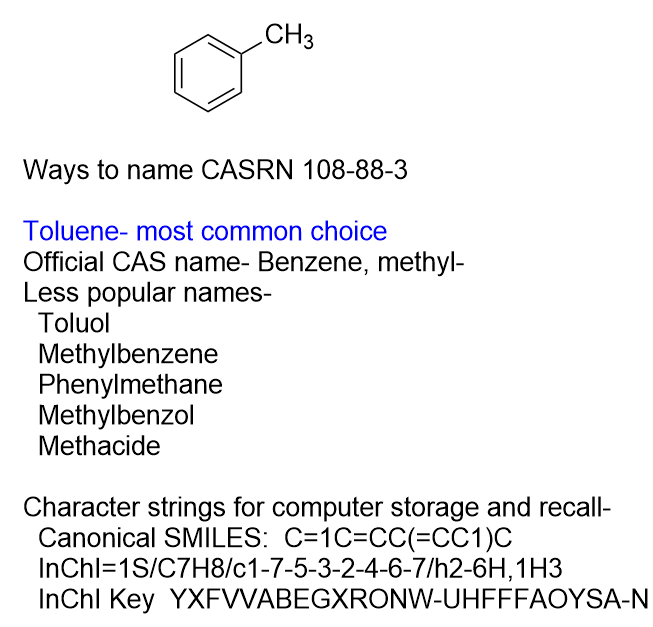

The systematic nomenclatures I will be referring to are IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) and CAS (Chemical Abstracts Service) supported by the American Chemical Society. I am unaware of the volume of usage of Beilstein and Gmelin databases today. They appear to be ongoing. Not being a German speaker, I’ll use first CAS then IUPAC in that order of priority. CAS and the few other databases use a numbering system for each unique substance in addition to the name. The CAS registry number, CASRN, is used around the world for authoritative identification of chemical substances. This includes academic R&D, industry, Safety Data Sheets, transportation, emergency response and not just in the USA. CAS also manages the TSCA registry list for EPA.

Many chemicals have names that pre-date systematic modern naming conventions like toluol or methylbenzol (methylbenzene, toluene) or vinegar acid (acetic or ethanoic acid). These older, trivial names are deeply entrenched in common usage and the secret cabal of nomenclature mandarins lets it pass uncontested.

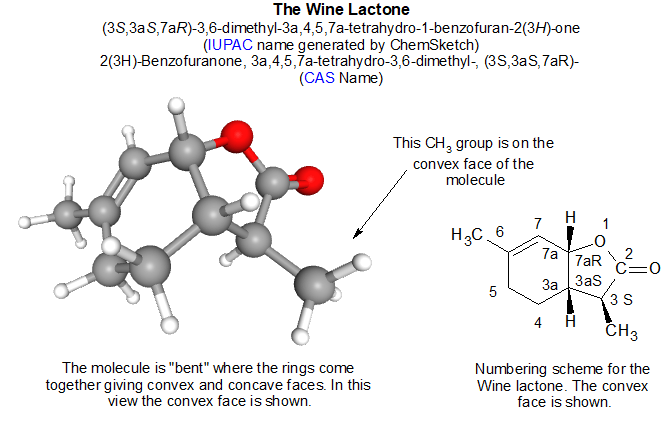

Above is a ball and stick 3-D model of the Wine Lactone and next to it is a diagram of the numbering system for the molecule. While any fool could number the atoms, it takes a special one to make it official. The heading of the graphic gives the IUPAC name of the lactone as done by a chemical graphics application called ChemSketch. For comparison, the CAS name is given as well. The CAS database entry for the structure gives a very slightly different version of the same thing.

R&S designations can be omitted if they are not known. Adding R&S to the structure gives a spatially accurate view. It is not uncommon for a structure to be disclosed and given a CASRN before any R or S features are known.

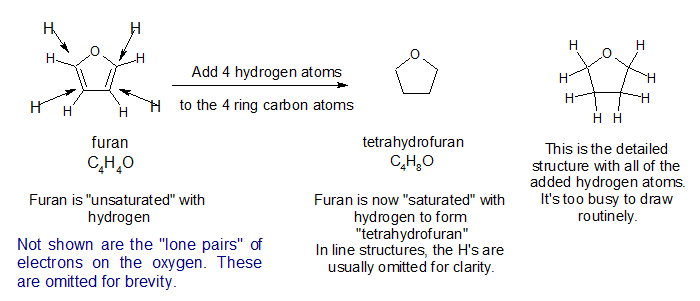

The starting point for assigning a name is to decide what the core structure is, noodle through its numbering and then begin identifying the fragments on it. Somebody in the murky depths of time determined that the core structure of the Wine Lactone is a variety of 5-membered ring called a “furanone” (FYUR an own). The C=O (carbonyl, CAR bun eel) part could be in two places so we’ll have to account for that. With non-carbon atoms in the ring, the non-carbon atom is usually given the place number of “1”.

Both CAS and IUPAC have publications on organic ring structures, however in my experience IUPAC does not show the numbering scheme as CAS would. CAS holds a list of all known ring systems.

Question: Why doesn’t sophomore organic chemistry teach CAS nomenclature rather than IUPAC. Answer: I don’t know other than IUPAC has been taught for a good long time and is usually limited to fairly simple molecules in class. I suspect that the professor’s background as well as the textbook content are involved.

Before we go on, we notice that a hexagonal 6-membered ring is attached at two adjacent places to the 5-membered ring. This is a “ring fusion” and fused 6-membered rings are often given the radical “benzo”. So, the core structure is a type of “benzofuranone”. Oh yes, here a radical is a word fragment added to a name to indicate the presence of something.

Starting with oxygen at position 1 we go around the edge of the fused ring skeleton clockwise and attach numbers to the carbon atoms that are not part of the ring fusion. In the graphic above you can see that there were ring atoms that received simple digits. The atoms that make up the fusion are named by taking the number of the atom that precedes it and adding the character “a” to it.

So, what do we know already? We have a benzofuranone with C=O (carbonyl) at position 2. The “one” radical of furanone indicates that the furan ring has a carbonyl group in it.

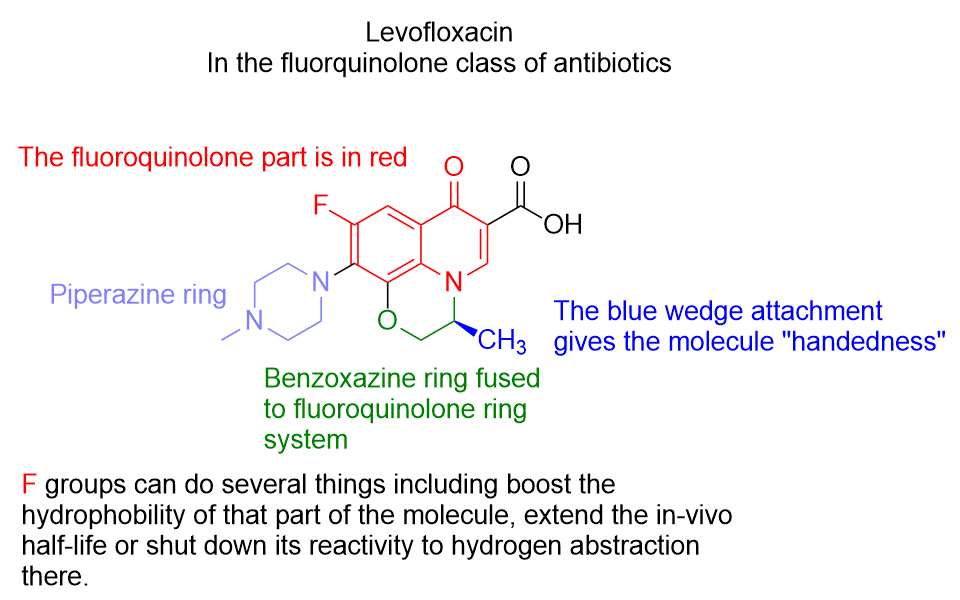

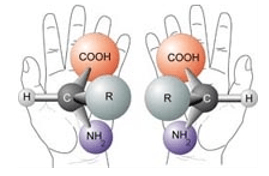

Next we must account for the way in which the molecule is arranged in 3-dimensions. Carbon atoms need to have 4 bonds (lines) connected to them. If all of the lines are single, the carbon has 4 atoms arranged around it in the shape of a tetrahedron with the attached atoms at the 4 vertices. A wedged line means that the atom at the end is jutting up and out of the plane of the page. Dashed lines indicate that the group on the end is jutting down below the plane of the page, but the artistic license here is that the dases are omitted. Notice that there are 3 wedged lines at positions 3, 3a and7a. The two hydrogen atoms (H) are projecting up out of the page as is the CH3 (methyl) group. This tells us that the two rings are jutting behind the page, so this molecule is not flat but bent. The name of the molecule has to indicate this.

The carbon atoms at 3, 3a, and 7a are called stereocenters because they have molecular handedness. Note that each is connected to four different groups in the molecule. It sounds like crazy talk but it is quite important. We won’t burrow into details here. Suffice it to say that these atoms will have an extra letter to designate what kind of “handedness” they have. R is for rectus meaning right-handed and S is for sinister meaning left-handed. There are rules for determining R vs S which we will not go into here.

Handedness in a molecule isn’t important except in how they interact with other molecules with handedness. The two nonsuperimposable (chiral) mirror images are said to be “enantiomers” (eh NAN tee oh mers). This is an issue for crystal structure and for many biomolecules. Outside of this, it isn’t much of a concern.

We now have (3S, 3aS, 7aR) to be plopped into the name. This group is shown in parentheses.

Next, we tackle the “tetrahydro” radical- it indicates 4 more hydrogen atoms are present than what would otherwise not be there. In nomenclature they start with rings that are unsaturated in hydrogen, meaning that the carbon skeleton is not connected to as many hydrogen atoms as it could. The four positions where a single hydrogen has appeared are 3a, 4, 5, 7a on what would otherwise be double bonds. There is one more to account for. The namesake furan molecule would have a double bond at position 3. In this molecule there is a hydrogen atom in place of the double bond, so 3H is added with the CH3 group.

So far we have (3S, 3aS, 7aR) and 3a, 4, 5, 7a-tetrahydro and 2-benzofuranone.

At positions 3 and 6 there are two CH3 or methyl groups. To account for position and the fact there are two of them leads to this part of the name- “3,6-dimethyl-“. Elsewhere in the name we denote the R or S configuration, if any. The CH3 at carbon 6 is flat so it lies in the plane pf the page- it is neither R nor S. But the CH3 at carbon 3 juts out of the page at us rather then pointing downward. It has been given the S configuration.

Putting it all together in the CAS name, the configurations at relevant atoms are given first followed by a hyphen then the hydrogen locations followed by a hyphen then the word “tetrahydro”. After tetrahydro radical and a hyphen, the methyl positions 3,6 are added followed by a hyphen then radical “di” attached to the radical “methyl” followed by a hyphen then the core structure 2(3H)-Benzofuranone. The “2(3H)” feature indicates that the carbonyl is at position 2 and an H is at position 3, indicating that the furan ring is connected by single bonds.

I describe here the name of the Wine Lactone in its extended CAS form rather than the parsed form. If you want to sort numbered chemical names alphabetically, leading digits just complicate the sorting. So if you sort alphabetically by the core structure, you rearrange the name to lead with Benzofuranone followed by the details trailing off in the distance as in the first graphic.

(3S,3aS,7aR)-3a,4,5,7a-tetrahydro-3,6-dimethyl-2(3H)-benzofuranone.

I’m sure that deep within the lower catacombs at Chemical Abstracts in Columbus, OH, there are grizzled old nomenclature wizards who may quibble with my explanations, but let them materialize before me in a puff of smoke and discuss the error of my ways.