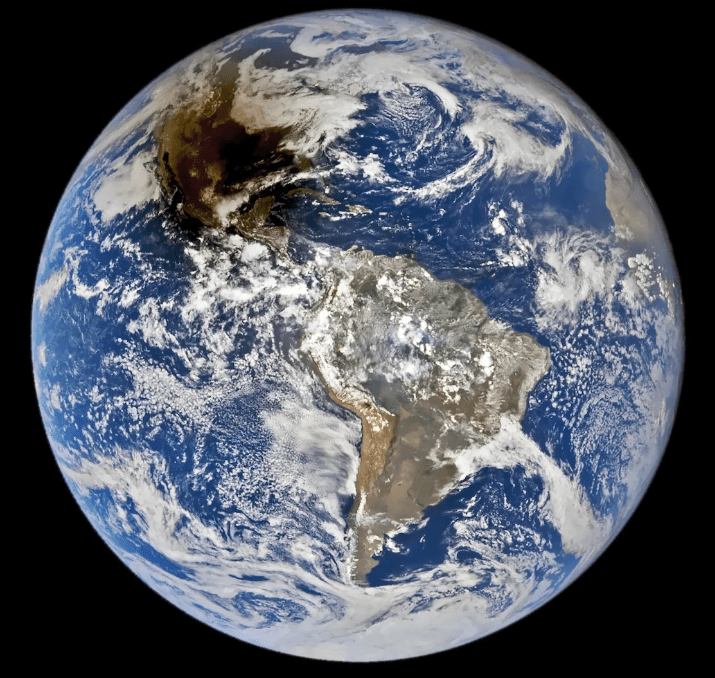

Here in Colorado, we were located north of the totality band in the partial annular eclipse region that swept across the US last week. I’ve seen annular eclipses previously so it was a been-there-done-that event for me. Below is a great photograph from NASA showing the eclipse from the DSCOVR (Deep Space Climate Observatory), a satellite jointly operated by USAF, NASA and NOAA. This satellite is in a non-repeating Lissajous orbit at the Lagrange point L1 about 1.6 million kilometers from Earth. It has also been called a looping halo orbit. At this location, it has a perpetual fully illuminated view of the Earth which rotates below it. The exception would be when the moon is in this part of its orbit.

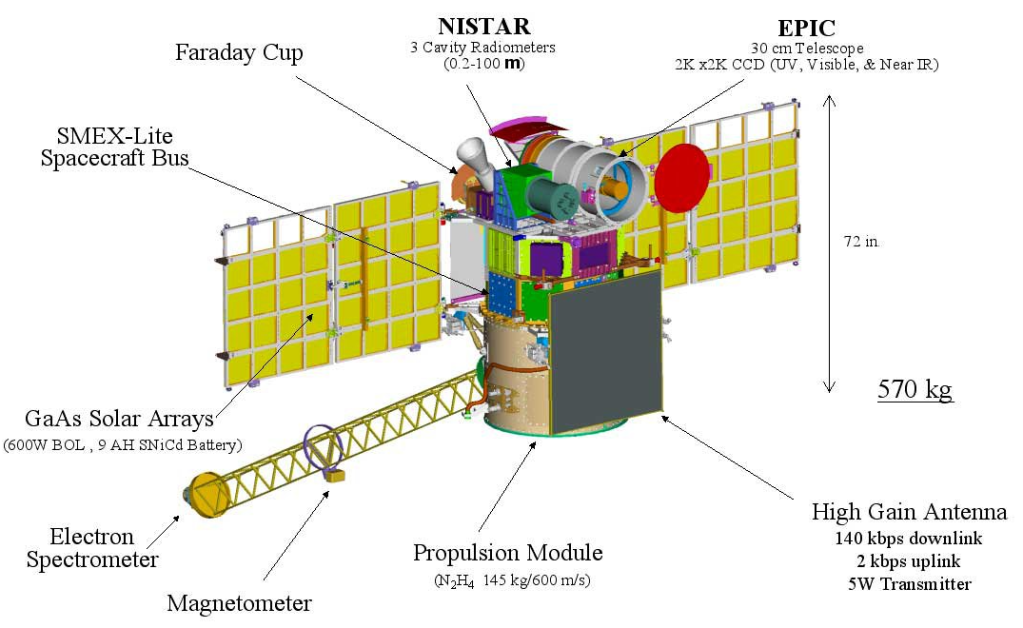

The probe carries numerous sensors to allow measurements of the earth and space environments.

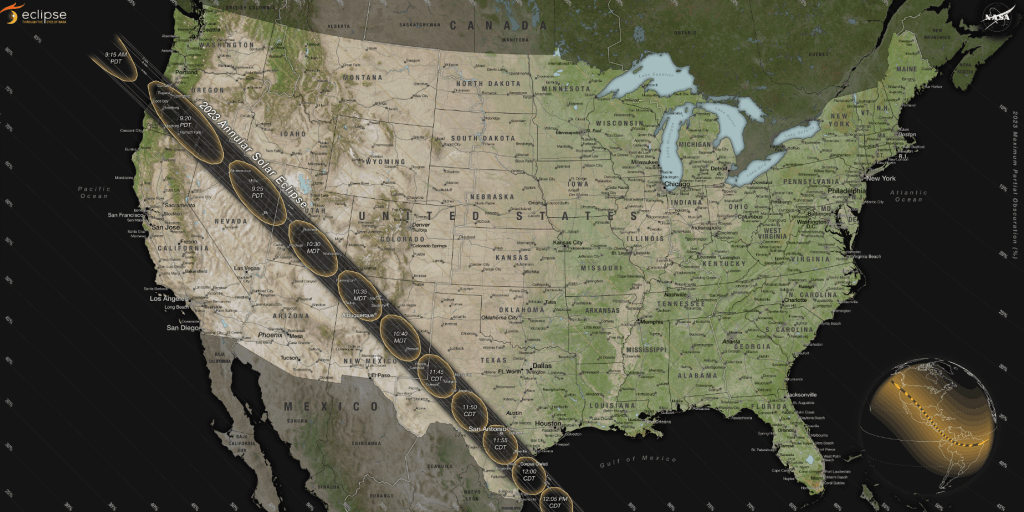

The band of totality stretched across the southwestern states October 14, 2023.

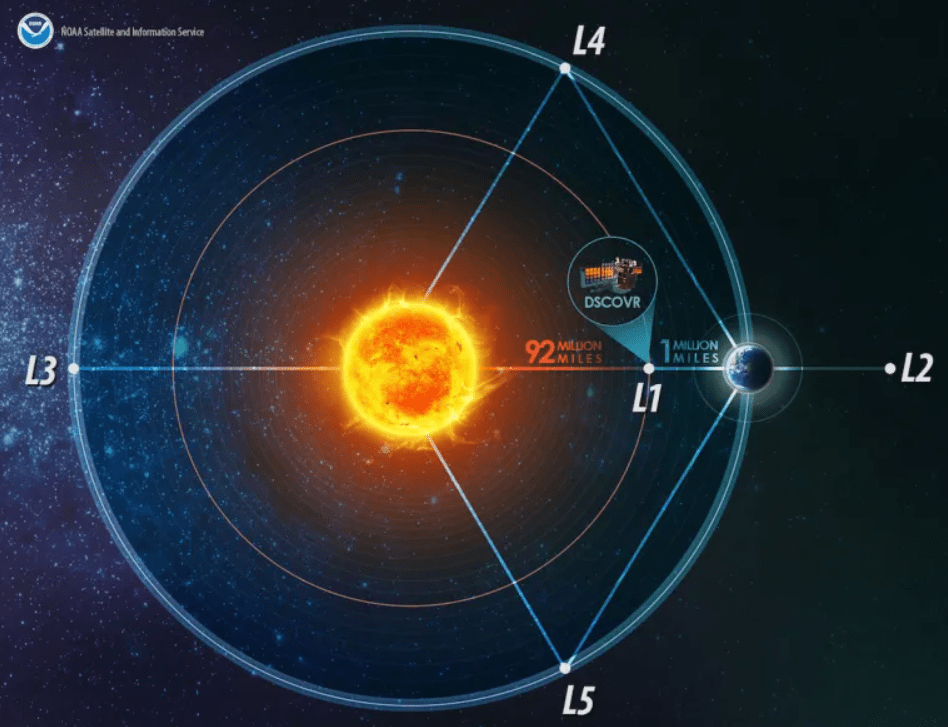

Lagrange points arise from two large masses in gravitational proximity, in this case the sun and the Earth. Relative to the two large masses the 5 Lagrange points allow for stable “parking orbits” for small objects like a satellite. Objects are placed in orbit around the Lagrange points to remain roughly stationary in relation to the Earth-Sun system.

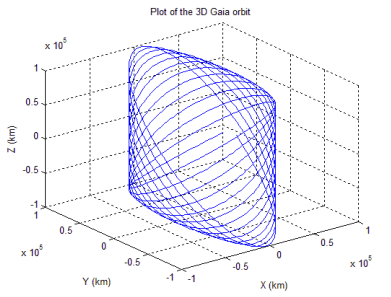

According to Wikipedia, a Lissajous orbit differs from a halo orbit in that it is quasi-periodic and dynamically unstable, needing occasional station-keeping actions by the probe. A halo orbit about a Lagrange point is described as a periodic, 3-dimensional orbit.

The history of the probe is a bit odd. It was launched by SpaceX on a Falcon 9 v1.1 launch vehicle on 11 February 2015, from Cape Canaveral. DSCOVR, initially called Triana after Rodrigo de Triana, the first European explorer to see the Americas. The mission began as a proposal by Vice President Al Gore in 1998 as a whole earth observatory at the L1 point. The probe’s mission was put on hold by the Bush Administration in January 2001 and officially terminated by NASA in 2005. The probe was placed in nitrogen blanketed storage until it was again funded, then removed and tested for viability in November 2008. The Obama Administration funded it for refurbishment in 2009 and the mission was fully funded by 2012. The Air Force allocated funds in 2012 for its launch and awarded SpaceX the contract. On February 11, 2015, the probe was finally launched from Cape Canaveral, FL. Management of DSCOVR is provided by NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center.

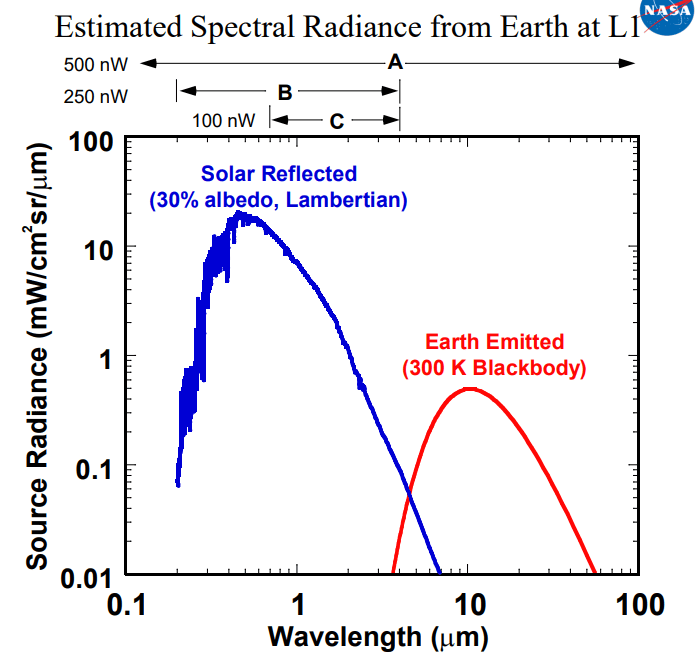

The NISTAR instrument on board the DSCOVR probe was provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST. NISTAR is a 4-band cavity radiometer and is located as shown below in orange. It measures reflected and emitted light in the infrared, visible and ultraviolet parts of the spectrum. The instrument is able to separate reflected light from Earth’s radiant emissions.

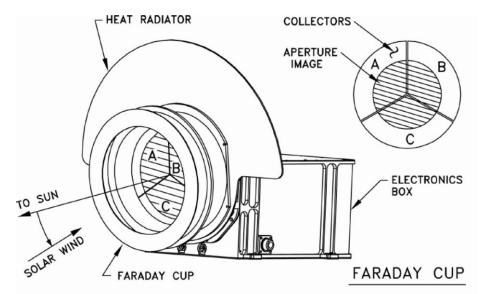

The Faraday Cup (FC) is a sensor that collects and quantifies the flux of positively charged particles in the solar wind, i.e., protons and helium nuclei. Variations in the solar wind speed are observed. In the course of operation they discovered that the solar wind is “colder” than was previously thought in terms of what is referred to as “thermal speed.” The researchers presented thermal speed numbers on the order of 300 to 500 km/sec.

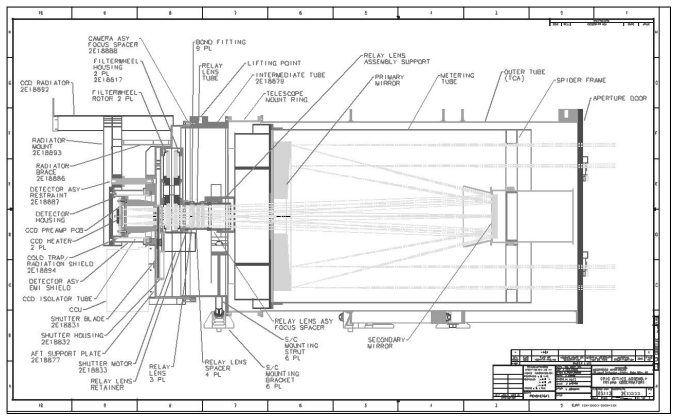

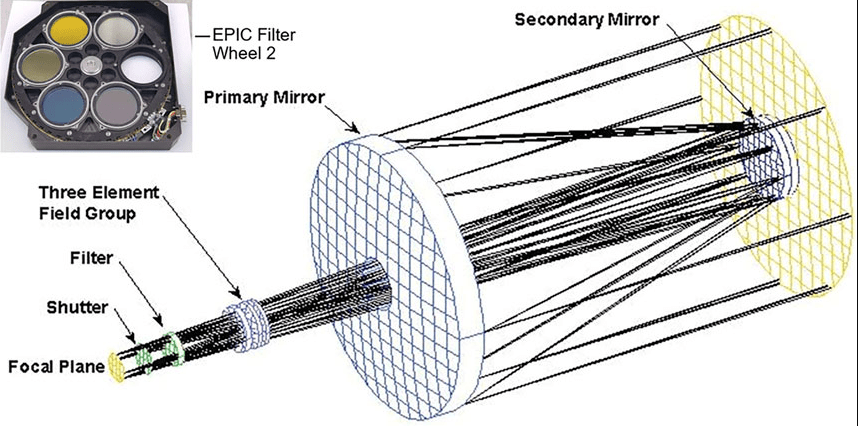

Schematic of optical system of EPIC.

- 1SciGlob Instruments & Services LLC, Elkridge, MD, United States

- 2Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA, Greenbelt, MD, United States

- 3LuftBlick, Innsbruck, Austria

- 4Science Systems and Applications, Inc., Lanham, MD, United States

- 5Joint Center for Earth Systems Technology, Baltimore, MD, United States

The probe has a 420 kg dry mass and its solar panels provided an initial 600 watts at 28 volts. The probe attitude and translational motion is managed with a set of 4 reaction wheels and 10 hydrazine thrusters. The hydrazine, N2H4, monopropellant is decomposed over a bed of catalyst prior to ejection. This decomposition yields hot N2, H2 and NH3 gases.

Like many satellites, DSCOVR uses reaction wheels for attitude control. Of the 4 reaction wheels, 3 are for axis-control and the 4th is used as a spare. Each wheel is driven by an electric motor. When the angular velocity of a single reaction wheel changes, there is a proportional counter rotation, resulting in a change in attitude about that 1 axis. Since the wheel velocity can be precisely controlled by the electric motor, fine adjustments in attitude can be attained.