While cockeyed optimists are working toward a new age of electric vehicles in the glare of an admiring public, I find myself standing off to the side mired in skepticism. What are the long-term consequences of large-scale electrification of transportation?

The industrial revolution as we in the west see it began as early as 1760 and continues through today. Outwardly it bears some resemblance to an expanding foam. A foam consists of a large number of conjoined bubbles, each representing some economic activity in the form of a product or service. A business or product hits the market and commonly grows along a sigmoidal curve. Over time across the world the mass of growing bubbles expand collectively as the population grows and technology advances. Bubbles initiate, grow and sometimes collapse or merge as consolidation and new generations of technology come along and obsolescence takes its toll.

The generation of great wealth often builds from the initiation of a bubble. The invention of the steam engine, the Bessemer process for the production of steel, the introduction of kerosene replacing whale oil, the Haber process for the production of ammonia and explosives, and thousands of other fundamental innovations to the industrial economy played part in the growing the present mass of economic bubbles worldwide.

After years of simmering on the back burner, electric automobile demand has finally taken off with help from Tesla’s electric cars. Today, electric vehicles are part of a bubble that is still in the early days of growth. The early speculators in the field stand the best chance of winning big market share. A major contribution to this development is the recent availability of cheap, energy dense lithium-ion batteries.

Of all of the metals in the periodic table, lithium is the lightest and has the greatest standard Li+/Li reduction potential at -3.045 volts. The large electrode potential and the high specific energy capacity of Lithium (3.86 Ah/gram) makes lithium an ideal anode material. Recall from basic high school electricity that DC power = volts x amps. Higher voltage and/or higher amperage gives higher power (energy per second). Of all the metals, lithium has the highest reduction potential (volts).

Rechargeable lithium batteries have high mass and volume energy density which is a distinct advantage for powering portable devices including vehicles. Progress in the development of lithium-ion batteries was worth a Nobel Prize in 2019 for John B. Goodenough, M. Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino.

All of this happy talk of a lithium-powered rechargeable future should be cause for celebration, right? New deposits of lithium are being discovered and exploited worldwide. But cobalt? Not so much. Alternatives to LiCoO2 batteries are being explored enthusiastically with some emphasis on alternatives to cobalt. But, the clock is ticking. The more infrastructure and sales being built around cobalt-containing batteries, the harder it will become for alternatives to come into use.

One of the consequences of increasing demand for lithium in the energy marketplace is the effect on the price and availability of industrial lithium chemicals. In particular, organolithium products. The chemical industry is already seeing sharp price increases for these materials. For those in the organic chemicals domain like pharmaceuticals and organic specialty chemicals, common alkyllithium products like methyllithium and butyllithium are driven by lithium prices and are already seeing steep price increases.

Is it just background inflation or is burgeoning lithium demand driving it? Both I’d say. Potentially worse is the effect on manufacturers of organolithium products. Will they stay in the organolithium business, at least in the US, or switch to energy-related products? It is my guess that there will always be suppliers for organolithium demand in chemical processing.

A concern with increasing lithium demand has to do with recycling of lithium and perhaps cobalt. Hopefully there are people working on this with an eye to scale up soon. A rechargeable battery contains a dog’s lunch of chemical substances, not all of which may be economically recoverable to specification for reuse. In general, chemical processes can be devised to recover and purify components. But, the costs of achieving the desired specification may price it out of the market. With lithium recovery, in general the lithium in a recovery process must be taken to the point where it is an actual raw material for battery use and meets the specifications. Mines often produce lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide as their output. Li2CO3 is convenient because it precipitates from aqueous mixtures. It must also be price competitive with “virgin” lithium raw materials as well.

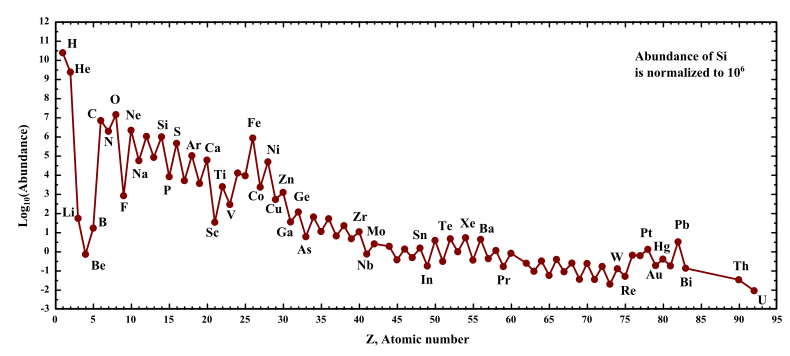

Lithium ranks 33rd in terrestrial abundance and less than that in cosmic abundance. Unlike some other elements like iron, lithium nuclei formed are rapidly destroyed in stars throughout their life cycle. Lithium nuclei are just too delicate to survive stellar interiors. The big bang is thought to have produced a small amount of primordial lithium-7. Most lithium seems to form during spallation reactions when galactic cosmic rays collide with interstellar carbon, nitrogen and oxygen (CNO) nuclei and are split apart from high energy collisions yielding lithium, beryllium and boron- LiBeB. All three elements of LiBeB are cosmically scarce as shown on the chart below.

Lithium is found chiefly in two forms geologically. One is in granite pegmatite formations such as the pyroxene mineral spodumene, or lithium aluminum inosilicate, LiAl(SiO3)2. This lithium mineral is obtained through hard rock mining in a few locations globally, chiefly Australia.

Chemical Definition: Salt; an ionic compound; A salt consists of the positive ion (cation) of a base and the negative ion (anion) of an acid. The word “salt” is a large category of substances, but for maximum confusion it also refers to a specific compound, NaCl or common table salt. In this post the word refers to the category of ionic compounds.

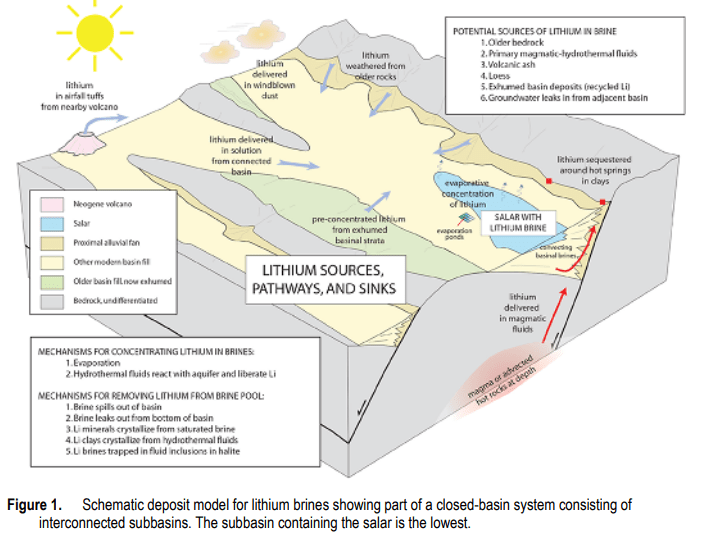

The other source category is lithium-enriched brines. The US Geological Survey has proposed a geological model for brine or salt deposition. According to Bradley, et al.,

“All producing lithium brine deposits share a number of first-order characteristics: (1) arid climate; (2) closed basin containing a laya or salar; (3) tectonically driven subsidence; (4) associated igneous or geothermal activity; (5) suitable lithium source-rocks; 6) one or more adequate aquifers; and (7) sufficient time to concentrate a brine.”

Lithium and other soluble metal species are extracted from underground source rock by hot, high pressure hydrothermal fluids and eventually end up in subsurface, in underwater brine pools or on the surface as a salt lake or a salt flat or salar. These deposits commonly accumulate in isolated locations that have prevented drainage. An excellent summary of salt deposits can be found here.

Critical to any kind of mineral mining is the definition of an economic deposit. The size of an economic deposit varies with the market value of the mineral, meaning that as the value per ton of ore increases, the extent of the economic deposit may increase to include less concentrated ore. If you want to invest in a mine, it is good to understand this. A good opportunity may vanish if the market price of the mineral or metal drops below the profit objectives. Hopefully this happens before investment dollars are spent digging dirt.

Lithium mining seems to be a reasonably safe investment given the anticipated demand growth unless страшный товарищ путины invasion of Ukraine lets the nuclear genie out of the bottle.

Just for fun, there is an old joke about the definition of a mine-

Mine; noun, a hole in the ground with a liar standing at the top.