Global demand for helium is expected to double by 2035. Helium is a critical, non-renewable resource used across the world. It is found in natural gas deposits in limited number of gas wells. Helium is the second most abundant element in the universe behind hydrogen. But this is averaged across the universe. Any helium the earth’s early atmosphere may have had has long ago diffused into space. At present, helium from terrestrial sources is derived from radioactive decay of uranium, thorium and daughter products within the Earth over eons of time. Underground structures suitable for the accumulation of natural gas may also accumulate helium.

Helium is useful in science and industry for many reasons, but mostly for its extreme chemical inertness and ultra-low boiling point. A gas with a very low boiling point, and if you manage to condense it, finds use as a low temperature coolant. Helium serves as an inert atmosphere in many applications including nuclear power, semiconductor manufacturing, welding and for pressurizing rocket propellant tanks. In liquid form, it boils at the low absolute temperature of 4.2 Kelvin (-261.1°C) and is indispensable as a cryogen for many applications from medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and quantum computing to other superconductor applications. Those of us who make great use of nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) are highly dependent on it as an analytical tool. NMR has made identification and quality control possible in many kinds of chemical manufacture.

According to one source a single MRI unit can contain up to 2000 Liters of liquid helium and consume 10,000 Liters over its 12.8-year lifespan. If you condensed the helium gas into liquid from the balloons at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, there would be enough liquid helium to keep two MRIs running for their lifetimes. The US presently has approximately 12,000 MRI units across the country. The good news is that helium recycling equipment can be fitted on to an MRI machine to greatly extend the life of a helium charge. Usually, a liquid helium dewar is immersed in a liquid nitrogen filled dewar which is inside a vacuum insulated container. The liquid nitrogen bath helps with the helium boil-off somewhat, even though the bp of nitrogen is considerably higher than that of helium, yet much lower than room temperature.

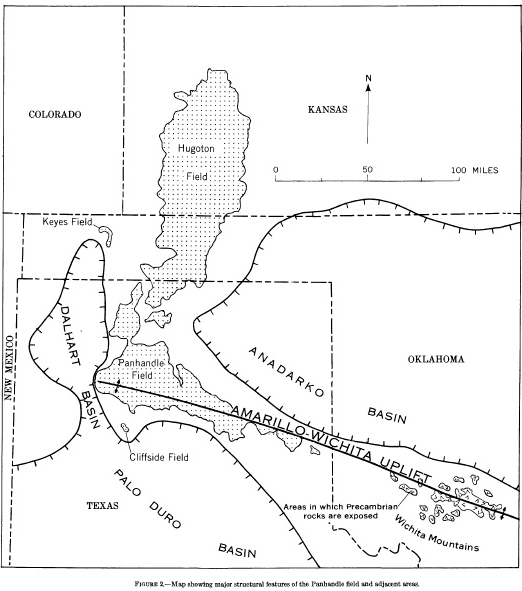

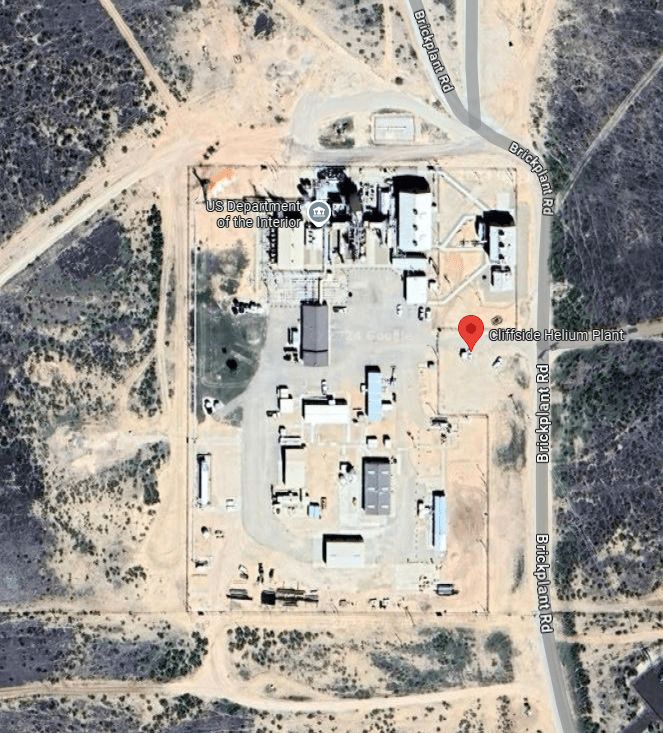

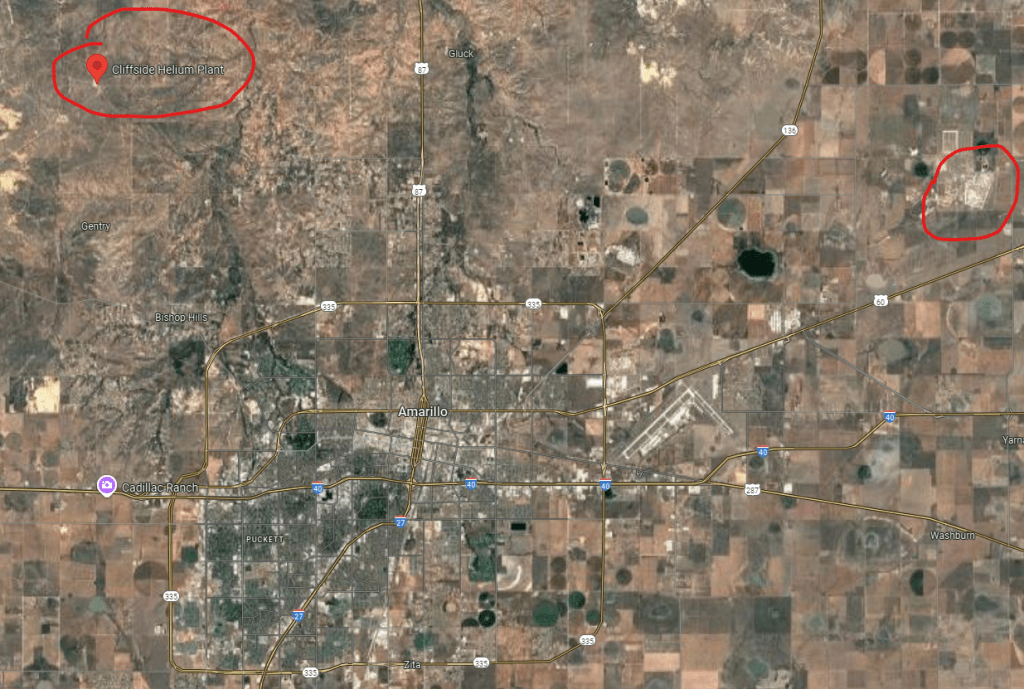

Helium is isolated from natural gas. According to the American Chemical Society, the US, Algeria and Qatar have the major the helium reserves while the US, Russia and Algeria are the top suppliers of helium. The majority of US reserves are in the Texas & Oklahoma panhandles and Kansas. The Cliffside helium plant is located a 15 miles NNW of Amarillo, TX, over the Cliffside dome. It is in the red circle on the upper left in the photo.

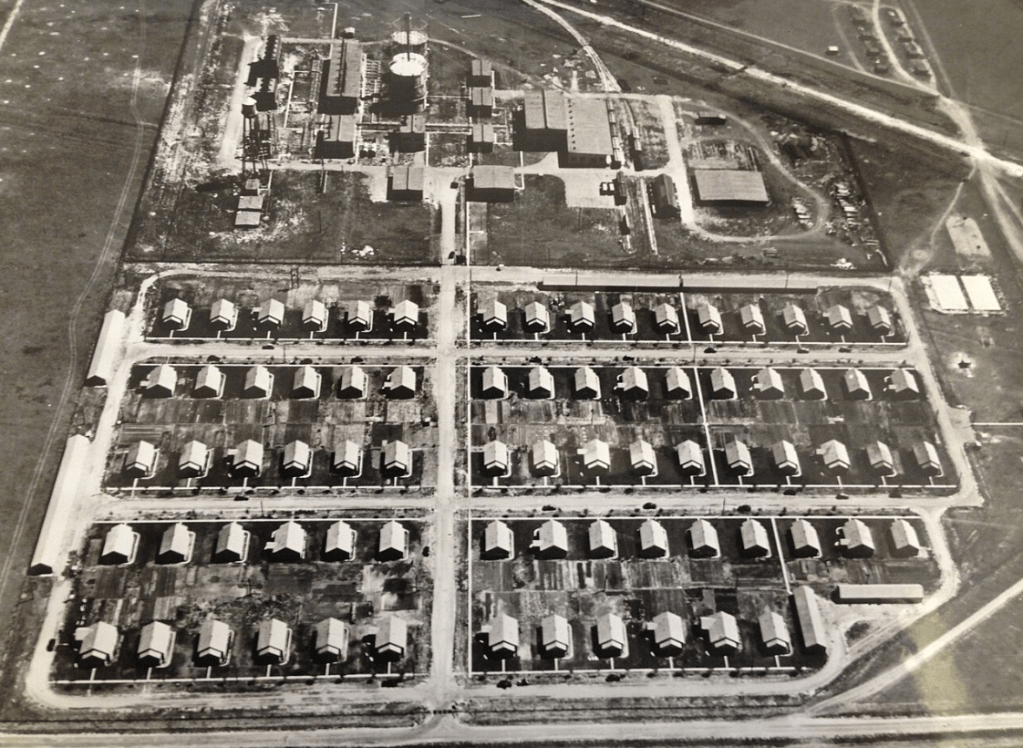

The Amarillo Helium Plant got its start in 1929 when the federal government bought 50,000 acres NNW of Amarillo for a helium extraction plant. The motivation was to accumulate helium for lighter than air aircraft like balloons and blimps.

It is interesting to note that the Pantex nuclear weapons plant is about the same distance but to the NE of Amarillo, TX. It is circled in red in the upper right. It is the primary site in the US where nuclear weapons are assembled, disassembled or modified. Uranium, plutonium and tritium bearing components are stockpiled there. Weapons that use tritium in their booster gas have a shelf-life constraint due to tritium’s very short half-life, so the gas must be periodically upgraded.

The facility opened in 1942 for the manufacture of conventional bombs and was shut down shortly after the Japanese surrendered in 1945. The site was purchased in 1949 by what is now Texas Tech and used for research in cattle-feeding operations. In 1951 it was surrendered to the Atomic Energy Commission (now the National Nuclear Security Administration) under a recapture clause.

So, we might ask the question: Why was anyone looking for helium in natural gas at the time? The easy answer is that nobody was looking for it. In May of 1903 in Dexter, Kansas, a crowd had gathered at a natural gas well to celebrate this exciting economic find. A celebration had been planned and the towns folk were there to see it ignited. It was called “a howling gasser” and there was much anticipation of a spectacular fire. After much ballyhoo and speeches, a burning bale of hay was pushed up to it in anticipation of ignition of the gas jet, but the burning bale was extinguished. This was repeated several times, but no fire. The disappointed crowd wandered off. Later Erasmus Haworth, the State Geologist and geology faculty member at the University of Kansas, got word of this curious event and managed to get a steel cylinder of gas sent to the university.

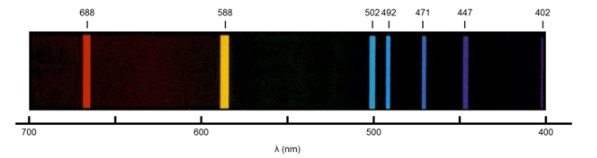

At the University Haworth and chemistry professor David F. McFarland determined that the composition of the Dexter gas was 72 % nitrogen, 15 % methane and 12 % of an “inert residue.” Soon, McFarland and chemistry department colleague Hamilton P. Cady began “removing the nitrogen from the gas sample by applying a spark discharge with oxygen over an alkaline solution.” This tedious procedure was soon replaced by using a glass bulb of coconut charcoal immersed in liquid air. This method had been shown to adsorb all atmospheric gases except helium, hydrogen, and neon at the temperature of boiling liquid air” (-310° F). The unabsorbed gas was collected in a glass tube and examined by emission spectroscopy. The spectrum showed all of the optical lines of helium. This discovery by McFarland and Cady showed that sizeable quantities of helium did exist on the Earth. The total amount of helium in the Dexter gas was 1.84 %.

The nagging question I have is how did the nitrogen content in the Dexter sample come to be? The thinking is that N2 gas found in natural gas derives from chemical alteration of organic ammonium compounds deep in the natural gas forming strata. To a chemist “ammonium” has a specific meaning. To a geologist it may just mean “amine”: hard to tell. N2 molecules are in a deep thermodynamic well, meaning that once formed, the nitrogen is very stable and not readily altered without large energy inputs. So, the formation equilibrium of N2 could favor its formation rather than returning to a precursor.

The removal of nitrogen, called nitrogen rejection, is a normal part of natural gas processing. The incentive for its removal is that it lowers the BTU content and thus the value of the gas. According to one source, the Midland gas field in the Permian formation of Texas is unusually high in nitrogen, from 1 % to 5 %. Given that the usual specification for nitrogen content is 3 %, excessive nitrogen must either be reduced by dilution or removed.

The problem of nitrogen becomes especially acute for gas that is condensed to LNG (Liquified Natural Gas). Natural gas that has too much nitrogen in it has a higher partial pressure of nitrogen and as a result it occupies space in a pipeline or LNG carrier that could be occupied by a gas that pays- natural gas. Non-combustible gas in the liquefaction train at the LNG terminal wastes its processing capacity. The specification mentioned above becomes more problematic when it is realized that the N2 content of natural gas may vary considerably from one wellhead to the next, adding to the overhead cost of quality control of the output gas.

Back to the Howling Gasser, the fact that the natural gas screaming out of the wellhead wouldn’t ignite was an extreme example of the effect of nitrogen in the formation. What saved the day was the high enrichment in helium. But, you would have to know to look for it. That a curious geologist and two chemists were able to isolate the helium and perform emission spectroscopy on it without a clue as to what it was stands as an excellent example of what curious, knowledgeable folks can do when given the resources. The state of Kansas is to be congratulated as well for providing the research facilities at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, KS.