[Note: Let’s get something straight here. I’m an industrial chemist and not a pencil-necked economist. I’m going to talk about some O&G economics from my industrial perspective. MAGA people are whining about increasing oil production to ease gas prices. My view is that these buggers are idiots, but I won’t say it like that. I’ll just discuss some pragmatics of oil refining.]

In an article published 10/1/24 in The Center Square the writer reports that a survey of voters in the key swing states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin that between 80% and 86 % of voters say that the price of daily necessities has gotten painful. Between 88 % and 94 % say they are concerned about inflation. This survey was obtained by Morning Consult/American Petroleum Institute poll obtained exclusively by The Center Square. “The poll surveyed nearly 4,000 registered voters Sept. 20-22 with a margin of error of 4%.”

From the article-

“Notably, the vast majority of voters in those swing states said more domestic oil and natural gas production would lower costs. Anywhere from 80% to 87% of those surveyed support more domestic energy production over more foreign production.” –The Center Square

Some refining basics

I think there is some misunderstanding generally about how the oil & gas (O&G) business works. First off, it is a global market and is subject to supply and demand pressures from all over the world. Second, there is O&G supply and there is refinery capacity. One might suppose that increasing O&G production domestically would automatically lead to lower fuel prices at the retail level. However, refinery throughput is limited to its particular capacity and storage. And, why would O&G producers increase output to an excess just to lower prices at the retail level? Leaving money at the table is against the instincts of every businessperson and is contrary to the fiduciary responsibilities of executives to stockholders.

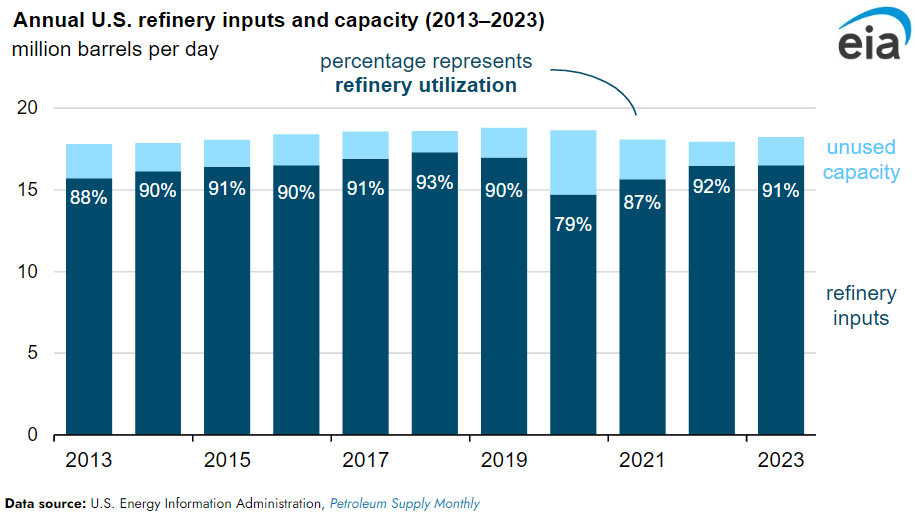

Refineries are usually operated at about 90 % capacity. Lest one think that refiners only need to tweak the throughput up a bit, it must be understood that it is unwise to operate a refinery or any other manufacturing plant at a constant 100 % capacity. Like any other factory, a refinery is subject to sudden or planned maintenance requirements, equipment failures, process upsets, variability in oil feedstock composition, hurricanes, variable demand in product spread or even infrequent operational error. A sudden unexpected shutdown can lead to a variety of complications as well as unleashing hazards at the large scale. Once a refining process line goes down, repair and restart can take one or more weeks to months to bring the process back to stable production.

A petroleum refinery is operated on a continuous throughput basis with series and parallel processing occurring simultaneously. Operating a refinery profitably is a complex job requiring a specialized skillset. As a PhD organic chemist, I am barely qualified to even set foot in a refinery, much less be of any kind of use there. Chemists may be found on site, but most likely in the quality control lab. These are the rarefied heights of the petroleum engineer.

A petroleum refinery is designed to take crude oil and gas inputs and shape them into an optimal spread of profitable products. The focus will be on maximizing the output of the most profitable products, especially motor fuels in the form of the various grades of gasoline and diesel. Your local gas station buys fuel from a wholesaler/distributor at a quoted price then sets a retail price depending on not just the wholesale price, but more importantly the local market prices and expected sales volume.

The general idea in pricing is this- always charge as much as the market will bear and adjust on the fly. There are two bookend pricing schemes available to the local gas station- specialty low volume/high margin pricing with minimum competition and commoditized high volume/low margin pricing due to competition. With electronic price displays at gas stations, prices can be adjusted very frequently. In most locations the time of day makes a difference in fuel sales volume.

Operating a refinery is a continuous flow exercise and is a bit delicate. A refinery is a web of continuous unit operations each with an input stream from one unit operation and an output stream to another operation. Each unit operation has a specific task to perform safely and efficiently. These unit operations subject the input hydrocarbon stream to heating, fractionation by distillation, and each of the many distillate streams are then subjected to their own unique processing. Other operations include alkylation, hydrotreating, sulfur scrubbing, catalytic cracking, isomerization, catalytic reforming, heat exchange, more distillation, blending and finally transfer to storage. Each operation is designed to process throughput at high flow rates to afford the best production rate of finished goods.

Waste process heat is directed to certain operations and used for greater efficiency. Oil refining inevitably produces light hydrocarbons whose recovery produces diminishing returns for recapture or comes from pressure venting where the vented gases are not suitable for recycle. In this case these gases are sent to a flare tower and burned. The flare tower plays an important safety role as it burns away flammable hydrocarbon gases that might otherwise accumulate and spread near the ground, posing a serious fire and explosion hazard.

Naturally, this requires considerable coordination to manage the rate of output of one operation to the input rate of the next. In fact the whole plant requires coordination of rates of throughput, pressure and temperature. A refinery is constantly monitoring and adjusting individual parameters with automation and human oversight to remain in “tune”.

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic and the reduction in demand, a number of refineries were shut down for maintenance or upgrades and a few were shut down permanently. This created a bottleneck in refining capacity nationwide and there was a shortfall in overall refinery output, leading to higher retail pricing of fuels as demand eventually rose.

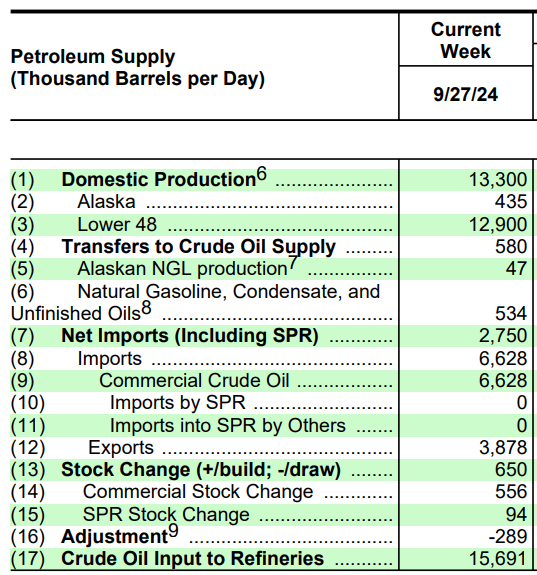

Today the USA both imports petroleum and exports it. The supply of crude oil and gas depends on contractual obligations and who is willing to pay the highest prices.

The United States in a net O&G exporter. Between imports and domestic output, the US is currently processing enough O&G for our needs with surplus to export. And what will an increase in domestic fracking really do for the US, again pricewise? It can increase the production yields at individual O&G wellheads bringing greater volume for the O&G producer over time. Done properly, fracking makes sense. However, if fracking provides a conduit for natural gas, oil or produced water into ground water, then it can be irredeemably harmful for those so affected.

Even if domestic O&G production is increased and released into the market, the near-term problem will be limited refinery capacity. The lead time for building a large oil refinery can be 4-5 years from design phase to commissioning. Permits, financing and societal pushback can add considerable time. Putting a complex refinery in the ground can cost $5-$15 billion. Startup and adjustment of a refinery is time consuming, complex and can be a bit hazardous. Accidents during startup and shutdown are not uncommon.

The politically popular opinion that what the US needs is an increase in oil production to drive down retail gas and diesel pricing rests on specious assumptions. The government provides regulatory oversight in many aspects of O&G production and refining. In my view, government oversight in regard to environmental protection and worker safety is of critical importance. Global free market control of O&G production and distribution, while often heavy handed and seemingly heartless, is the best model we have at present for production and distribution of hydrocarbon-based goods to consumers. For a historical example of government control of supply and distribution, we can look at the Soviet Union and its authoritarian centralized control of nearly everything. The Soviet model of governance and production of goods and services failed spectacularly by 1991. The leadership of the USSR dissolved the Soviet system themselves after concluding that it was no longer workable. For all of its many flaws, the overall western model of capitalism continued to thrive.

In short, it only makes sense to increase O&G production to keep retail fuel prices low if the refineries demand more crude to meet their distributor’s demand. Refined fuels could be imported for distribution here, but an uptick in storage capacity will likely be required. Refineries are fundamentally limited by their processing capacity. Refineries, like most manufacturing operations, are designed to provide an optimum output with the installed equipment. Greater throughput requires larger equipment or additional process streams

Anecdote: Every day I pass through the intersection of an east/west state highway and a north/south interstate highway. On the west side of this busy intersection there are four gas station/convenience stores competing for our gasoline and diesel business. Just a block to the west is a stoplight and at the four corners of this are three of the gas stations with direct access to the light. The fourth is not at the light so entry or exit to this station is not controlled by the light. During the early morning commute time, the four electronic signs indicate morning prices that invariably are $0.20 to $0.60 lower than mid-day prices. The tall electronic signs allow for convenient rapid response to competing prices. One station is beyond the single stoplight intersection, so both exiting eastbound vehicles and entering eastbound vehicles who need to turn left across uncontrolled heavy traffic have to wait for a break in the congested traffic. This is a competitive disadvantage for them. The other three stations have direct access to the stop light. Co-incidentally, the traffic-disadvantaged station nearly always has the lowest prices first. This tends to set the stage for a daily price war. This morning the 85-octane gasoline price was $2.719 at all four stations.

There are some plusses for the disadvantaged station mentioned above. Unlike the other three stations there is room for 18-wheelers to fill their tanks with diesel and park overnight next to a cheap motel and a Waffle House (Hey! Waffle House hash browns are the greatest). The left turn across traffic disadvantage to 4-wheelers is only a minor obstacle to the 18-wheelers using the station since they are apparently fearless in pulling into heavy traffic to execute a turn.

Econ 101 Conclusions

Like everything else, scarcity applies pressure on hydrocarbon prices up and down the supply chain- from wellhead to fuel tank. National politics can play a role in hydrocarbon pricing if it threatens to alter scarcity in some way. In chemical kinetics we are interested in finding the rate limiting step in a multistep chemical reaction. This step is the bottleneck that controls the overall reaction rate. In much the same way, a bottleneck in a supply chain will control the rate of output of a given product. The rate of delivery through the bottleneck controls the rate of wealth creation for those in the supply chain. To increase the rate of wealth creation, one must multiply the number of these bottlenecks in parallel or design a new bottle with a larger neck. Importantly, the rate of wealth creation can be a winning positive or a losing negative number. Excess capacity anywhere in the chain results from excessive money spent on unneeded production scale.

Note: There is much more to the macroeconomics of O&G production than what I have addressed. The economics of O&G production and distribution in the US depends on policy and regulatory factors as well as considerable anticipation and speculation (gambling) in the marketplace. Despite this, it is possible to make certain very broad statements in the context of general supply and demand principles. The finer, high resolution, details can be found elsewhere.