Atomic hydrogen (the major isotope protium) is the simplest, lightest and most abundant neutral atom in the universe. Molecular hydrogen, H2, is the simplest neutral molecule in the universe. Seems very simple. Well, hold on. Turns out that molecular hydrogen has two distinct forms and it relates to the business of nuclear spin.

Quantum mechanics (QM) is a basket of wavy weirdness. It is a model of the universe at the atomic and nuclear levels that is wildly different from the larger scale Newtonian universe of colliding billiard balls we humans casually observe. The QM model of the microscopic universe dates back to the early 1900’s and has been endlessly supported by experimental data, and it continues to surprise to this day. One of the fundamental QM quantities is ‘spin.’

Fundamental particles like electrons and protons have something referred to as spin angular momentum. In the larger scale Newtonian universe spinning is something that we equate with an object that is rotating about an axis. Protons have a measurable diameter- it is a finite sized object with mass, charge and spin. Electrons have mass, charge and spin also. However, electrons do not have a measurable size. They appear to be a point charge. So, how does an electron with no measurable size actually spin? What is it that spins? A point of clarification: Quantum spin has nothing to do with a rotating internal mass. It is a quantized wave property expressed in units the same as classical angular momentum (N·m·s, J·s, or kg·m2·s−1). So, what the hell is quantum spin?

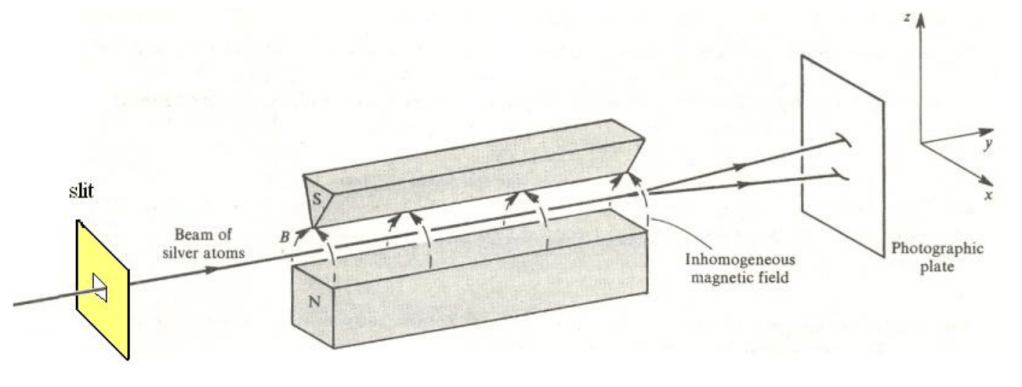

Spin angular momentum was inferred experimentally by the Stern-Gerlach experiment, which was first conducted in 1922. In this experiment, silver atoms were passed through a magnetic field gradient towards a photographic plate. Particles with no magnetic moment** would pass straight through unaffected. Particles with non-zero magnetic moment would be deflected by the magnetic field. In the experiment, the photographic plate revealed two distinct beams rather than a continuous distribution. The results indicate that the magnetic moment was quantized into two states. The magnetic moment at the time was thought to be due to the literal spinning of an electrically charged particle. They deduced that there were two spin configurations- i.e., they were quantized.

If you want to go deeper down the QM rabbit hole, be my guest. We’ll go forward with the notion of spin up and spin down. You’ll see how it works.

Atomic Hydrogen- Things Get Sciency

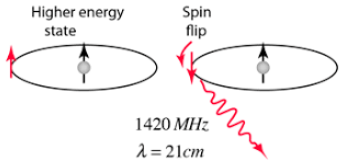

First, let’s look at a neutral hydrogen atom made of a proton and an orbiting electron. Both particles have spin and each can be in one of two states relative to the other- parallel and antiparallel or simply spin up and spin down for the sake of illustration. The spin combinations are up-up and down-up as shown in the figure below. Think of the arrows as bar magnets, so up-up would be two magnets with the north poles in parallel and the down-up would be bar magnets with magnetic poles facing opposite directions, or antiparallel. The arrangement where the magnets are aligned with identical poles in the same direction is less energetically favorable than when they are antiparallel. Since it is energetically down-hill, the up-up will want to flip to down-up or antiparallel lower energy state. The energy difference is lost as radio frequency radiation in the microwave band.

A spin flip to lower energy level results in the emission of a 1420 MHz (21 cm wavelength) radio frequency emission. This can be detected by a radio telescope though with some difficulty due to poor signal to background noise. Credit: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/quantum/h21.html

The spin transition energy is 9.411708152678(13)×10−25 Joules. Regions of space with more intense 21 cm radiation are thought to be regions of greater hydrogen atom abundance. These regions can be examined for redshifting to give clues about relative motion in space. The spiral structure of the Milky Way galaxy was discovered with 21 cm radio observations.

Molecular Hydrogen, H2

Molecular hydrogen consists of two hydrogen atoms that share a pair of electrons which provide the bonding force. The two electrons spend a finite amount of time between the protons canceling the repulsive force between them. It’s called a sigma bond. So far, so good. The bond is springy so the molecule can/does vibrate.

An unfortunate reality of chemistry– Like most topics, the more background you have on a chemistry principle, the more unifying and elegant it becomes. This means that sharing the beauty of the molecular world is a little more difficult that many would like. I regret this most sincerely. Most freshman chemistry involves balancing equations and PV=nRT math. Necessary but not always captivating. Freshman chemistry is much like the Hobbit in the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It’s a necessary prelude.

First, a Dive Down the QM Rabbit Hole

Ok. I couldn’t ignore the QM rabbit hole. The two electrons of an H-H bond must have opposite spins in order to form a covalent bond. An orbital represents a specific occupancy space for one or two electrons around an atom or molecule. They are places, not physical objects. The atomic orbital model is a mathematical construct based on spherical harmonics to define the shapes of space that electrons will occupy around the nucleus, depending on their energy and quantum numbers. The likelihood of finding an electron is wavelike within a region of space.

Two electrons can occupy one orbital if they have opposite spins. It’s referred to as spin pairing. (Note: I posted on the orbital stuff a few posts back.) This hard and fast rule of antiparallel spins occupying the same orbital is formalized by the Pauli Exclusion Principle. The Pauli Principle says specifically that “no two fermions with half-integral spins can occupy the same quantum state within the same quantum system“. Electrons are fermions and the upshot is that only 2 electrons of antiparallel spin can occupy a single orbital. If two or more orbitals of equal energy level are available, the electrons will occupy separate orbitals with the same spin. The manner of the filling of orbitals with electrons is covered by Hund’s Rule.

Finally, QM gives a number to an electron’s spin- the spin quantum number. According to the Pauli Exclusion Principle, two electrons in a single orbital must have different half-integral quantum spin numbers: +/- 1/2, or antiparallel- to occupy the same orbital space.

Credit: Wikipedia.

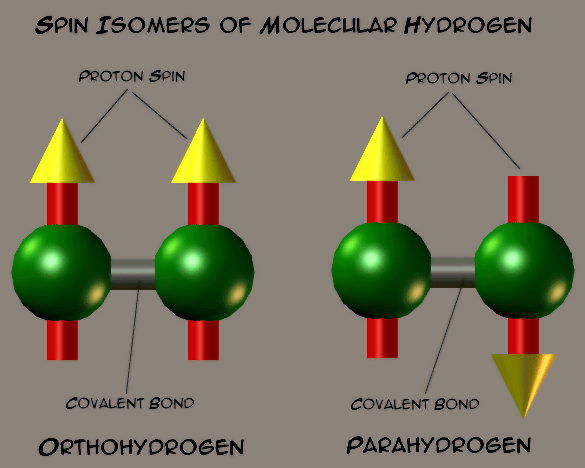

Because the two H-H electrons are spin paired, there is no net spin from them. However, the protons are a different matter. Their spins can be parallel (up-up or down-down) or anti-parallel (up-down). The anti-parallel spins cancel to give no net proton spin to the H-H. But, in the case of spin parallel, the H-H molecule definitely has net spin.

The spin parallel H-H molecules are called orthohydrogen and spin antiparallel H-H molecules are called parahydrogen. They are referred to as spin isomers or allotropes and are each distinct substances. There can be interconversion from orthohydrogen to parahydrogen molecules. The transition does not emit radiation, but it is exothermic. The parahydrogen is more stable by 1.455 kiloJoules (kJ/mol) per mole. Heating hydrogen will bring the composition to a maximum of 25 % ortho to 75 % para. When hydrogen is liquified, there is a slow conversion of ortho to para. It is worth noting that the enthalpy of evaporation of normal hydrogen (1:3 ortho to para) is 0.904 kJ/mol which is smaller than the 1.091 kJ/mole for 1:3 ortho to para conversion enthalpy for “normal” hydrogen. The conversion of orthohydrogen to parahydrogen in liquid form is exothermic and can result in hydrogen boil-off, leading to hydrogen loss and possibly causing a hazardous pressure rise. Those who regularly handle liquid hydrogen must be aware of this phenomenon. Orthohydrogen can also be catalytically converted to parahydrogen by contact with certain substances like ferric oxide, chromic oxide as well as several materials.

** Magnetic moment (from Wikipedia): magnetic moment is the magnetic strength and orientation of a magnet or other object that produces a magnetic field.