In my industrial career as a PhD organic/organometallic chemist I was kept busy for about 10 years with in-house Reaction Calorimetry (RC), Accelerating Rate Calorimetry (ARC), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) as well as Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for validating thermal process safety. To institutionalize this I was asked to start a process safety department and began standardizing experimental protocols and a database for the results. I was able to scour the internet for thermochemical papers, looking for mentions of energetic properties. As always, much can be learned by just looking around.

Thermal process safety refers to safe operation of chemical manufacturing in regard to the generation of heat in a reaction mass and the hazards arising therein. The hazards from uncontrolled self-heating include acceleration of reaction kinetics producing accelerating heat and pressure evolution. If the reaction enthalpy and subsequent temperature rise theoretically exceeds the boiling point of the solvent despite the cooling jacket and the chilled condenser, then self-heating can lead to a boil up and uncontrolled ejection of the reaction mass. With insufficient cooling, the temperature will rise to the solvent bp and boil off the solvent first, carrying much heat away as heat of evaporation. Once most of the solvent has boiled away and if the reaction mass continues to self-heat, the temperature will continue to rise and peak at some undesired level as the reactants are consumed. Further heating of the now hot, highly concentrated reaction mass, potentially leading to successive reactions that may or may not be exothermic.

When a liquid phase reaction mass self-heats faster than heat can be removed, the reactor pressure will begin to rise. As pressure builds, the boiling point of the reaction mass begins to rise, slowing down the boil-off. A sudden drop in pressure, as with the burst of a rupture disk, will cause a superheated solution to promptly boil throughout the reaction mass. This means that flash vaporization can lead to bubble formation throughout the volume of the reaction mass producing a foam. The severity will depend on the pressure drop and the bp of the solvent. If the headspace is sufficiently small, the foam can expand rapidly and begin to exit through the vent pipe. A properly engineered vent pipe has been sized to vent gas/vapor at specified conditions. Since a foam is part liquid and part gas/vapor, it lacks the overall compressibility of a gas/vapor so the resulting foam flow may be lower than calculated for a gas/vapor, slowing the rate of depressurization.

The distinction between gas and a vapor is that a vapor may be condensable as with most solvent vapors, but evolved gases like hydrogen, methane or carbon dioxide will combine with a non-condensable blanket gas like nitrogen and resist condensation in the by the chiller. The point is that if one is relying on a chilled condenser to knock down non-condensable gases as a pressure management control, then a rude shock is headed your way, especially if the rupture disk bursting pressure is higher than need be.

Flow into vent pipes that exit outdoors may discharge hot reaction mass onto the roof or wherever the vent terminates. If the vent terminates into a knockdown drum or other catch vessel, the hot reaction mass contacts whatever may be in those vessels.

Fortunately, the thermal profile leading up to the above scenario can be modeled in properly conducted RC1 experiments. But exactly what can be done beforehand?

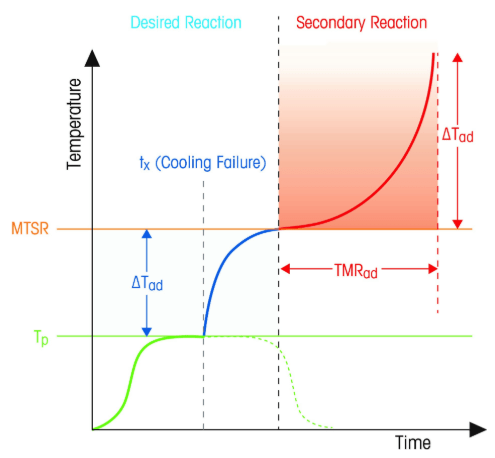

First, let’s realize that the total self-heating temperature rise can be measured. We add that ΔT (temperature rise) to the proposed reaction temperature Tr and get a maximum temperature of the synthetic reaction, MTSR. Once we have this, if the MTSR is greater than the bp of the solvent(s), then we know that an uncontained runaway is possible. What to do then?

- R&D needs to justify the problematic low boiling solvent with the reaction temperature to be applied.

- R&D needs to provide input on lowering the design reaction temperature.

- Is a lower Tr for a longer reaction time feasible?

- How sensitive is the reaction to a higher bp solvent substitution?

- If the chosen solvent conveniently forces side or waste products to precipitate and be removed by filtration, then we have the conundrum of safety vs efficient processability.

- The magnitude of the hazard in the minds of everyone involved may be quite different and will require a documented decision process. Engineering input here is invaluable.

- Tp Process Temperature

- ΔTad Adiabatic Temperature rise

- MTSR Maximum Temperature of the Synthetic Reaction

- TMRad Adiabatic Time to Maximum Rate

- Tx Time of Cooling Loss

What if the design solvent is truly required for a feasible and economic process? This needs to be discussed first with chemists and engineers in the room and a decision rendered. If chemist input says no solvent change is desirable or economic, the engineers need to speak up as to whether there is an engineering work around. If a ready engineering work around is not feasible and the product is still important, then the chemists need to be challenged to find procedure that denies the equipment a runaway condition.

If we’re lucky, a partial batch reaction method can be used wherein the reactor is charged with solvent and most of the reactant compounds are in the vessel at the beginning of the run. The final reactant is slowly fed into the reactor and the reaction temperature is controlled by the feed rate. Reaction calorimetry can be used to arrive at a plausible maximum feed rate that is fast but not too fast. A reaction calorimeter is basically a chemical reaction detector and can be used to look for an approximate reaction onset temperature. Remember that onset temperature is not a physical or chemical property. It depends on the detection equipment and the rate of heating.

Like everything else, success can depend on first asking the right questions. On the graphic computer display of the RC1, you can determine the response to an aliquot of reagent addition. Does the heat production, q, rise promptly with addition or does it lag? If there is a lag or a latency, it means that over-charging by operators at scale can happen if they are looking for a prompt “heat kick” on addition of the feed.

The RC1 can also show the length of time to react away the feed or what the total reaction time may be If the reaction has a natural response lag, then a defined charge mass is called for. A response lag may also be due to the presence of water which must first be quenched under the reaction conditions. The most insidious situation is when the feed reactant accumulates in the reactor over the course of the reaction. This is very difficult to judge by the operators. The feed may accumulate until the reaction suddenly begins and accelerates out of control. This is not uncommon.

Finally, a proper “batch reaction” is one in which all of the reactants are loaded into the reactor all at once, the temperature is adjusted and the reaction begins. It is critical that before a new batch reaction is allowed, the chemists must show that this will not result in a runaway condition. This is where reaction calorimetry shines. The safety of a batch reaction is reproduced in the RC1and the progress is monitored. The RC1 can also be used to explore various reaction conditions to see if runaway potential can be easily blundered into. How narrow are the safe operating parameters? Many plant incidents happen at shift changes where the continuity of watchfulness may diverge for a time, even with automation.

TMRad Adiabatic Time to Maximum Rate

A very informative piece of data to have is the TMR- Time to Maximum Rate. This can be obtained by an Accelerated Rate Calorimeter or ARC. The instrument consists of a furnace into which is placed a sample “can” which can be made of metal or glass. The furnace raises the sample temperature gradually using a heat-wait-search (HWS) method searching for an onset temperature.

Once an onset temperature is found, the HWS is automatically halted and the furnace keeps adjusting its temperature to match the rising internal sample temperature. If the internal sample temperature and the exterior furnace temperature are the same, then the sample is under adiabatic conditions and no heat flows in or out of the sample can. The sample temperature is driven by self heating only.

Knowing the sample mass and the best guess at Cp, constant pressure heat capacity, the reaction enthalpy can be determined. From the data, the Time to Maximum Rate (TMR) can be calculated to give an equation. It is the time that a substance that is self-reacting takes to reach the maximum rate of heat output as a function of sample temperature. The instrument also records sample pressure. If the sample pressure does not return to ambient pressure at room temperature, this would mean that a non-condensable gas was evolved.

A typical ARC experiment took me from 6 to 24 hours to complete the HWS routine.

What TMR data allows one to do is to find a reaction temperature the reaches maximum rate in 24 hours or more. You plug in a temperature and you get a TMR. The temperature needed to produce a TMR of 24 hours is considered by many in industry to be the uppermost safe processing temperature. It helps to answer what the maximum safe temperature in which a solid can be dried before decomposition begins.

To outsource safety testing or not

First and foremost, a commercial safety test lab understands and uses procedures that are agreed upon and standardized. Also, if down the road there comes a related event, your response to criticism will be to refer to the test lab experts, not some ham fisted employee monkeying around in the lab doing improvised experiments. Certain safety matters should be referred to the commercial lab experts for valid results and for CYA. This applies especially to energetic materials like nitroaromatics or nitrate esters.

Chemical manufacturing is conducted at many scales from laboratory gram scale products for R&D, multi-kilogram kilo-lab batch processing to the colossal commodity scale continuous manufacturing of petrochemicals, agrichemicals, polymers, flavors & fragrances, and pharmaceuticals. Nearly all of these commodity chemicals and polymers are well known and have safety issues related only to flammability, exposure and dose.

Outsourcing tests that can be done inhouse is a missed opportunity to accumulate more skills which is company treasure. I’m speaking of calorimetry. Calorimeters can be brought on-site and meshed in with research and development. Just learning how to interpret thermograms alone brings workers new insights into their chemistry.

What is best for your company? In-house safety testing or outsourced safety testing? Like nearly everything else in life, the answer depends on the situation. If you need to survey for explosive hazards for the first time, there are several competent commercial labs available that will use standard protocols. My experience is that they employ just engineers or a mix of chemists and engineers. They conduct standard testing protocols wherein a series of samples are exposed step-wise to a series of ever increasing stimuli intensity to find the boundary conditions of sensitivity to various stimuli, like heat, friction, impact, dust explosion parameters, burn tests, static charge lifetimes and minimum ignition energy (MIE) with electrostatic discharge.

Explosibility testing

Sensitivity to explosive behavior is tested in numerous ways to flesh out the sensitivity profile. Testing is performed in stages where the least intense stimuli are tried first to screen for highly sensitive substances. The results of any single test run are graded as ‘Go/No Go’ or ‘positive/negative’. The terms ‘Go’ or ‘Negative’ mean that an explosive property was observed.

Part of explosives testing is finding out what kinds of stimuli lead to initiation of an explosion. The Bureau of Mines (BOM) drop weight test looks for the maximum safe impact energy. There is a friction test, an electrostatic discharge test, and many others. If the sample does not give a Go result at the maximum machine impact or friction, then it is regarded as safe under those precise conditions. In the BOM test, the higher the number (in drop distance of a 5 or 10 kg weight), the more stable it is to impact.

You get the testing data. Now what?

Now how do you take numerical test data and convert it to safer operations? This is where engineers can be most useful. Imagine a substance that has a 34 inch BOM drop weight result with a 10 kg anvil. Will any process equipment mash down on the substance inadvertently? Put this ball in the court of engineers and let them chew on it. This data moves workers closer to confidence in safety.

Outsourcing safety testing and explosive screening can lead to a conundrum. Outsourcing anything means that certain expertise may not be internalized for your company’s use, the user or manufacturer. Commercial labs will absolutely not comment on how the material can be safely used, whether or not it is too dangerous or nominally safe under your use conditions. Safe use is not an endorsement they will make, they will only stand behind their results from standard testing protocols. I’d do the same.

Before safety testing you were alone. Now, with safety data, you are still alone but with numbers. Engineers and plant operators are invaluable in locating equipment that delivers impacts or friction. They can also help to identify non-grounded equipment that may generate or accumulate electrostatic charge. Always get the plant people involved.

It didn’t take long to realize that if we sent samples out to commercial labs for calorimetry testing, the samples were subjected to unfamiliar standard test methodology. Early on it was fascinating to see what kind of experimental setups were used and what the results looked like. Being a synthesis chemist I was unfamiliar with calorimetry. My earlier exposure to calorimetry was limited to what appeared in molecular dynamics and mechanics modeling. Acquiring actual data on reaction enthalpies and onset conditions myself awakened a fascination that carried me far into reaction calorimetry and thermochemistry.

What was not clear at the outset of receiving external calorimetric, electrostatic and explosive test data was what to do with it. Using external hazard data to inform operational procedure was new to everyone. Yes, we could learn from an ARC experiment what temperature the onset to a runaway condition begins, but how to use the measurements in practice wasn’t always obvious.

Incidents have three phases- initiation, propagation and termination. You have to ask this: if an incident initiates, what is the preferred propagation direction to termination? Yes, this can be controlled somewhat but only in advance. For instance, if an explosion happens, what is the least terrible direction for the blast to go? These matters should be considered in the design phase of construction of a chemical facility. If they weren’t, then decisions must be made despite the lack of preplanning.

As an example, a commercial explosives company I’m aware of built their manufacturing facility out in the European countryside. Explosive materials were prepared, stored and handled in small buildings distributed over a large area with distance, berms and trees separating them. If an explosion happened, the blast wave would be isolated from other assets and attenuated by distance, berms and forest. Here, the propagation phase was suppressed by distance and topography.

Another explosion highlights the folly of not segregating manufacturing operations. A plant manufacturing a hydroxylamine called HOBT suffered a catastrophic incident where a reactor blew apart explosively during a process previously performed many times. The reactor was housed in a structure that had expanded over time by adding manufacturing space by piecemeal addition as needed. This resulted in a building that was a rabbits warren of rooms and hallways even including admin space. The explosion did not just happen without warning. The reactor began to overheat from accumulating heat of reaction and became unresponsive to cooling efforts by the operator. As the operator turned to go get help, the reactor exploded sending parts up and out of the building, with the agitator landing on the roof of an adjacent business and onto railroad tracks. Heat transfer oil ran out of the building and flowing into the nearby river. The operator was blown through a sheet rock wall but survived. The shock wave propagated into adjacent spaces and down hallways, blowing out windows, internal and external doors including overhead doors.

The sad thing is that another plant suffered a devastating explosion 20 years earlier making the same hydroxylamine product. Perhaps lessons were learned at this plant, but those lessons didn’t to the other plant.

The lesson is clear. In chemical manufacture the R&D folks must be sure that all chemical properties are well understood and such knowledge is a part of accessible in-house expertise. If there is no R&D, meaning that a large scale procedure is simply written up and performed without the scrutiny of cold expert eyes evaluating it, then you are stepping onto a high wire without a net. Both plants making the hydroxylamine had experienced chemists on site and performed the procedure without incident many, many times. Even then, incidents happened but how many incidents were averted by expert judgement? We’ll never know.

Experience

Let’s talk about experience. Career chemists are like everyone else- they may have accumulated years of experience. Some of the learning’s a person has accumulated are captured in writing and available to staff. Other learning’s reside in a person’s head only and are perhaps regarded as ‘obvious’. Or the serious hazards are actually disclosed on the Safety Data Sheet which was filed away without scrutiny. Knowledge of explosibility of a particular substance could be too narrow by virtue of time and obscurity to serve as walking around knowledge by many chemists. Some of us are accustomed to spotting explosive functional groups (explosophores) on a molecule but many are not.

For some individuals, their 18 years of experience is better described as 6 years repeated twice, or worse. Years of experience should always imply years of continuous improvement.

The main reason that process safety was a separate department was to prevent production and R&D from having vested interest in how test measurement results were interpreted and used or ignored. If calorimetric data suggests that a particular process reaction can run away or if a reaction should be initiated and run at a lower temperature, managers personally responsible for productivity may object owing to increased plant time or lower processing yields. This is especially problematic if prior experience has never shown a hint of a hazard, yet. Or, incidents in the past were not taken seriously or properly understood. The phrase “we’ve always done it this way” can be a very difficult barrier to overcome. And even if overcome, can revert back to the old practices over time.

This forces management to deal with safety margins and acceptable risk. They should automatically understand that zero risk is not possible. However, they may look back over the production history and not realize that they spent too much time near the edge of disaster.

Unknown risks

Imagine wearing a blindfold while standing 2 meters from the rim of the Grand Canyon. Someone turns you around a few times to scramble your senses. Now, even while not knowing the location of the rim, it is possible to walk around blindfolded and not go over the edge. You could do this for a short or a long time period and not fall in. Slowly you begin to doubt the hazard is real since you have not gone over the edge. Soon the risk is forgotten in the frenzy to reduce costs. Then one day you fall into the canyon and on the way down you muse about your own folly.