“Technological triumphalism” is a term that occasionally surfaces, encapsulating the belief in human capacity to resolve almost any issue through the innovative use of technology. While technological progress has led to pivotal breakthroughs, such as rational pharmaceuticals, aerospace and the transistor, it has also given rise to the means to magnify age-old human tendencies towards destructive behaviors. As our tools and methods evolve with technological advancements, so too do our desires and avarice, often intensified by the fresh opportunities these new technologies bring to the table.

As an example of technology bursting on the scene producing both good and bad consequences, consider the Haber-Bosch process for the industrial manufacture of ammonia, NH3. The Haber-Bosch process has been called the most important chemical process in the world. An industrial product like ammonia can split into several streams. On the plus side, cheap and available liquid or gaseous ammonia for fertilizing crops was a boon for mankind in terms of increased food production. As a chemical feedstock, the combination of ammonia and its oxidation product, nitric acid, led to the economic production of the solid fertilizer ammonium nitrate.

Another and wholly different product stream involving the oxidation of ammonia (Ostwald Process) is nitric acid production. Nitric acid is required for the manufacture of materials including high explosive nitrate esters like nitroglycerine and nitroaromatics like TNT, picric acid and a great many other explosives. Explosives are neither inherently good nor bad- their merits rest on the shoulders of the users. When used for construction or mining, explosives are a positive force in civilization. However, they cast a long, dark shadow when used to destroy and kill.

Fritz Haber: Ammonia and Zyklon

A good example of unanticipated consequences of a technology uptick is in the story of the German chemist Fritz Haber. Haber won the 1918 Nobel Prize for Chemistry for his part in the invention of the Haber-Bosch synthesis of ammonia. It is estimated that 1/3 of global food production relies on the use of ammonia from the Haber-Bosch process or some improved version. Haber has been widely praised for his part in the invention of catalytic ammonia production using atmospheric nitrogen. These are important developments, but … [Wikipedia]

As a German nationalist, Haber was also known for his considerable contributions to German chemical warfare through WWI. Early on, Haber suggested chlorine as an improved chemical weapon over tear gas during WWI and was later involved in the development of Zyklon B as a fumigant, pesticide and later a weapon of mass murder.

There is contradictory information as to who actually developed Zyklon B. One source claims the inventor was Bruno Tesch, Gerhard Peters and Walter Heerdt while another claims Haber developed it. The composition and story of Zyklon B is subject to confusion in a Google search. The actual contributions of Tesch and Heerdt to the production of Zyklon B was to produce sealed cannisters of HCN adsorbed onto a sorbent like diatomaceous earth along with a cautionary eye irritant to signal the presence of the HCN in the air. The early use of Zyklon B was to delouse clothing, ships, warehouses and trains. The Nazis began using Zyklon B to murder human beings in the concentration camps beginning in 1942 as well as delouse their clothing to stop the spread of typhus.

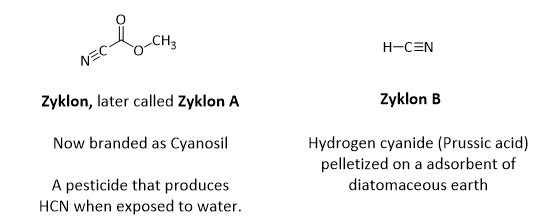

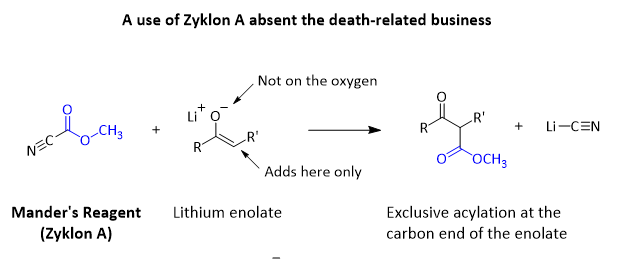

The identification of Zyklon, Zyklon A and Zyklon B is a bit confusing. Zyklon was originally developed as a pesticide. When exposed to moisture it hydrolyzed to form hydrogen cyanide which was the active toxicant. Lachrymatory warning additives were blended in to alert those exposed. Eventually, the Nazis requested that the warning additive be removed since it spooked the prisoners.

Tesch and Stabenow founded Tesch & Stabenow in Hamburg in 1924. The next year they became the sole distributors of Zyklon, manufactured by its patent holder, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlings-bekämpfung mbH (German Corporation for Pest Control), shortened to Degesch. Tesch & Stabenow was the exclusive reseller of the “Zyklon” which was produced by Degesch (founded 1919) whose director was Fritz Haber.

Tesch & Stabenow was founded in 1919 as a subsidiary of Degussa with its first director, Fritz Haber. Later, in 1936, Degesch was owned by its parent company Degussa along with IG Farben and Th. Goldschmidt AG (now Evonik). The company was said to be extremely profitable from 1938 to 1943 with sales of Zyklon B to the German government and Schutzstaffel (also known as the SS). After the war, Bruno Tesch, co-founder and owner of Tesch & Stabenow, and “director Karl Weinbacher were convicted and sentenced to death by a British tribunal and executed in Hamelin Prison on 16 May 1946.”

The only practical difference between the three Zyklon products was that Zyklon B contained and delivered HCN directly while Zyklon/Zyklon A requires water to decompose it, releasing HCN.

Cyanide

The history and chemical manufacture of all the various cyanides is rich in diversity. The word ‘cyanide’ is usually reserved for ionic compounds or hydrogen cyanide, HCN, or those that release cyanide anion readily.

The cyanide group, :Carbon-triple bond-Nitrogen:, is a functional group found in many natural sources.

The cyanide group, -CN, on an organic molecule is usually bound more strongly by covalent bonding though not often connected directly to a carbonyl group (C=O) where it is susceptible to loss as with Zyklon/Zyklon A. It is the connection of the cyanide group to an ester carbonyl group that is behind the ability of Zyklon/Zyklon A to release free cyanide. In Zyklon/Zyklon A, the carbonyl group (C=O) is subject to aqueous hydrolysis producing CO2, CH3OH and HCN.

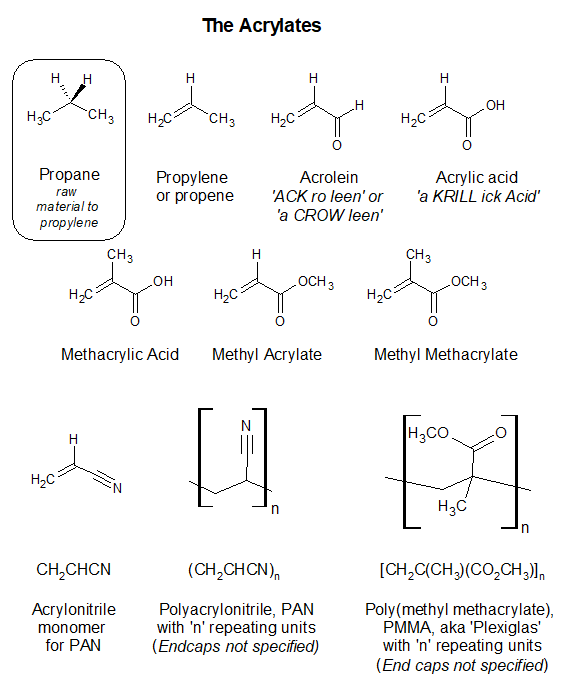

The word ‘cyanide’ is probably best limited to situations where the anion, :CN–, is present as a discrete chemical species. Common cyanides in use today are potassium cyanide, KCN and sodium cyanide, NaCN. KCN in water is commonly used in gold mining to selectively extract gold as a soluble cyanide complex, replacing the hazardous mercury amalgamation method. When covalently bonded to an organic molecule or to a polymer like polyacrylonitrile, the cyanide functional group is strongly bound. When CN is a feature of an organic substance where it is covalently bound to a carbon atom, it is referred to as a ‘cyano’ group, ‘nitrilo’ or ‘nitrile’ group. These words signify that the CN group is not present as a discrete anion but rather is tightly bound to an organic framework. This is less likely to spook the general public.

A swerve into the weeds with acrylates

It is said that neither Fritz Haber nor Carl Bosch were fans of National Socialism in Germany in the 1930’s. Haber claims to have done his WWI gas warfare work for Kaiser Wilhelm as a German patriot. Intimidated by German laws aimed at Jews and Jewish colleagues, Haber (a Jew converted to Catholicism) left Germany in late 1933 for a position as director of what is now the Weizman Institute in what was at that time Mandatory Palestine. He died in the city of Basel, Switzerland, while enroute to Palestine at age 65.

Haber’s work in chemical weaponry included the use of chlorine gas which was chosen for its density and would sink and collect in enemy trenches. Chemical warfare in WWI began with an idea from volunteer driver and physical chemist Walther Nernst (yes, that Nernst) who suggested in 1914 the release of tear gas at the front. This release was observed by Fritz Haber who recommended chlorine instead and later supervised Germany’s first release of chlorine gas at the Second Battle of Ypres in WWI. Well known German scientists involved in the development of chemical weapons included chemist Fritz Haber, chemist Otto Hahn, physicist James Franck and physicist Gustav Herz. Of the 5 scientists, Nernst included, all would receive a Nobel Prize in their lifetimes.

‘Haber defended gas warfare against accusations that it was inhumane, saying that death was death, by whatever means it was inflicted and referred to history: “The disapproval that the knight had for the man with the firearm is repeated in the soldier who shoots with steel bullets towards the man who confronts him with chemical weapons. […] The gas weapons are not at all more cruel than the flying iron pieces; on the contrary, the fraction of fatal gas diseases is comparatively smaller, the mutilations are missing”.’ Source: Wikipedia.

I don’t mean to demonize German scientists specifically since the 20th century was peppered with engineers & scientists from many countries who engaged in weapons of mass destruction research & development, both in the private and government sectors. Naively and from afar to nonscientists it might seem like scientists are a benevolent brotherhood or sisterhood of “do-gooders” bent on the application of science for the benefit of mankind. To be sure, all whom I have known understand the importance of basic science to society at large and are of high moral character, mostly. Note, though, that the phrase “do-gooder” is actually an insult. According to Dictionary.com it means “a well-intentioned but naive and often ineffectual social or political reformer.”

Even Yugoslavia’s Tito had chemical weapons and a nuclear weapons project out of fear of an attack by the Soviets. In the end the project amounted to little more than some research institutes to support the nuclear project. Eventually Tito cancelled the project. Yugoslavia did have its own deposits of uranium ore and developed a method of extracting uranium concentrates from it. In October, 1958, they had a nuclear criticality event within a teaching reactor of their own design.

It is hard for me to grasp that chemical weapons are a notch of evil above other conventional arms. Bullets fired from military-style small arms can kill instantly, slowly or cause survivable mutilation. High explosive charges from artillery, missiles, hand grenades or land mines can kill instantly, slowly or cause survivable mutilation. Is this somehow preferable to a chemical attack? Chemicals too can kill quickly, slowly or cause survivable mutilation. These chemical weapons can be either a gas or an aerosol which can deposit on surfaces and retain toxicity for some period of time. Both gases and aerosols can drift with the wind making them trickier to ‘aim’ and are subject to dilution by cloud or gaseous dispersion. Many have suggested that chemical warfare is more useful for its ability to terrorize a population than to kill.

High explosives are point sources of shock waves followed quickly by sharp flying metal fragments. Like all point sources of dispersing energy, the intensity of the shock falls off as some kind of inverse square law and fragments soon fall to the ground. The bullet or the artillery shell are projectiles that can be aimed, often with great precision, and deliver their kinetic energy or explosive charge to a distant location. This applies equally to cruise missiles, drones, jet fighter ordnance and other flying mayhem.

All of the weaponry mentioned above are the result of the application of chemical energy.

Rest stop along the highway of knowledge

At some point for all of us whose areas of specialty may overlap with weapons technology, we have to decide how we will confront it. We can pitch in to defense R&D and make a contribution or we can contribute to civilization in other ways. For myself, I chose to work on improving life through chemistry. Others can find better ways to destroy things.

For me, military aircraft are a guilty pleasure. I am absolutely in awe of the technology and the people who build and get them into the air. The stratospheric art of aerospace engineering is endlessly fascinating. Still, they are weapons platforms that exist solely for the purpose of killing and serving devastation. I understand the necessity of countries acquiring such deadly flying machinery. The monster Putin has provided the latest reminder of the importance of military readiness.

High explosives as a paradigm shift

The research and development of nitrate esters like nitroglycerine in the 1830’s and later nitroaromatics like nitrobenzene, picric acid and trinitrotoluene (TNT) rapidly led to the sometimes-inadvertent discovery of their detonability. The discovery led to the creation of a new class of explosives, marking a significant shift from the relatively slow burning of gunpowder to the high velocity detonation of “high explosives” such as picric acid or RDX. Unlike gunpowder, which needed to be confined to produce an explosion, the introduction of detonable nitroaromatic and nitrate ester explosives resulted in a large increase in the sudden release of energy. The availability of a relatively safe and easily produced explosive like TNT facilitates the leap of thought to the realm of armaments, especially when the explosive could yield considerable profits.