Note: Below is a quick safety brain-dump from a career in academic chemistry labs and chemical manufacturing facilities. It is not meant to be an unabridged guide to lab safety. Look elsewhere for that. it is easy to overlook Safety Data Sheets that come with chemical purchases.

At some time in their chemistry education the student should have had a good look at the chemical Safety Data Sheet or SDS for the chemicals and solvents they are using. While not necessarily very informative in terms of reaction chemistry, these documents are taken very seriously by many groups who can/will have an impact on your chemistry career and safety. Regardless of your walking-around-knowledge about a chemical substance, you should understand that the people who respond to emergency calls for a chemical incident will place a high reliance on what is disclosed on an SDS. A student who is connected with an incident won’t be the first point of contact when the fire department or ambulance arrives and wants information. In fact, it is highly unlikely that a student will ever have direct contact with a responder unless it is with an EMT.

When emergency responders arrive at the scene of your chemical incident, they will have protocols built into a strict chain of command. All information will pass through the responder’s single point of contact. The fire fighter with the fire hose is not the person you should try to communicate with. Information regarding the incident must be communicated up the chain of command from your site incident commander. The person responsible for the lab should know who that is. The staff at the incident site (your college) will also have protocols built onto a chain of command. Again, “ideally” the incident commander at the incident site will ask for information from others on the site regarding details on the event including the headcount (!) and communicate it to the incident commander of the responders. This is done to avoid confusing the responders with contradictory or useless information. Do not flood the responders with extraneous information. Don’t speak in jargon. If there are important points like “it’s a potassium fire”, pass it along. If there are special hazards like compressed hydrogen cylinders present, they’d like to know that too. Answer their questions then step back and let them do their job.

When responders arrive at the scene of a chemical incident, the first question they will ask is if everyone is accounted for. If everyone is accounted for, they will not risk their lives in the emergency response. However, if there are people unaccounted for or known to be trapped in a dangerous place or incapacitated, the responders will take greater chances with their own safety to rescue the victims. They will act to minimize property damage only if it can be done without risk to life and limb. Nobody wants to die saving property.

College chemistry departments that I have been involved with have had a flat policy of evacuating everyone from the building and congregating them at a defined location in response to an alarm. That way there is at least some reasonable chance that an accurate head count can be made. If technical advice is needed, faculty connected with the incident site should be consulted. The college will have an Environmental Health and Safety (EH&S) group or person who presumably will take charge of the incident on the incident side. The leader of EH&S should be informed of any hazards unique to the substance of concern if there is no SDS. Let them communicate with the responders. Generally, we chemists help most when we keep out of the way.

College chemistry departments are famous for housing one-of-a-kind chemical substances in poorly labeled bottles in faculty labs. These substances almost never have any kind of safety information other than perhaps cautionary advice like “don’t get it in your eye.” Luckily, university research typically uses small quantities of most substances except perhaps for solvents. Solvents can easily be present at multiples of 20 liters. These large cans are properly kept in a flammables cabinet. While research quantities may not represent a large fire hazard initially, there could easily be enough to poison someone. When you get to the hospital, the ER folks will have to figure out what to do with your sorry ass lying there poisoned by your own one-of-a-kind hazardous material.

In principle, the professor in charge of a chemistry research lab should be responsible for keeping an inventory of all chemicals including research substances sitting on the shelf. Purchased chemicals always have an SDS shipped with them. These documents should be filed in a well-known location and available to EH&S and responders.

The chemistry stockroom is a special location. Chemicals are commonly present at what an academic might call “bulk” scale, namely 100 to 1000 grams for solids and numerous 20 L solvent cans. The number of kg of combustibles and flammables per square meter of floor space is higher here. The stockroom manager should have a collection of SDS documents on file available to responders.

Right or wrong, people positively correlate the degree of hazard to the nastiness of an odor. Emergency responders are no different. This is another reason why it is critical for them to have an SDS. People need to adjust their risk exposure to the hazard present as defined by an SDS. We all know that some substances that are bad actors actually have an odor that is not unpleasant for a short time, like phosgene. Regardless of this imperfect correlation, if you can smell it, you are getting it in you and this is to be avoided. Inhalation is an important route of exposure.

In grad school we had an incident where a grad student dropped a bottle in a stairwell (!) with a few grams of a transition group metal complex having a cyclooctadiene (COD) ligand on it. Enough COD was released into the stairwell to badly stink it up. They didn’t know if it was an actual chemical hazard or not, so they pulled the fire alarm handle. The Hazardous Material wagon showed up right next to 50-60 chemistry professors, postdocs, and grad students. The responders were told what happened and with what, so they dutifully tried to find information on the hazards in their many manuals. They did not find anything.

They had 50-60 chemists within spitting distance but didn’t ask us any questions. This is because they are trained to respond as they did. This was a one-off research sample of a few grams but it had an obnoxious smell with unknown hazards. Finally they sent in some guys in SCBA gear and swept up the several grams of substance and set up a fan for ventilation. Don’t be surprised if the responders don’t have special tricks up their sleeves for your chemical event. They can’t anticipate every kind of chemical incident.

Long story short, both the responders and the chemists didn’t have any special techniques tailor made for this substance. There was not evident pyrophoricity or gas generation. It was a dry sample so no flammable liquids to contend with. The responders used maximum PPE and practiced good chemical hygiene in the small clean up. Case closed.

An SDS is required for shippers as well. It shows them how to placard their vehicles according to the hazards. Emergency responders need to see the SDS in order to safely respond to an overturned 18-wheeler in the road or to a spill on a loading dock. It could also be that the captain of container ship wants to know precisely what kind of hazardous materials are visiting his/her ship.

Finally, an SDS should be written by a professional trained to do it properly. By properly I mean by someone who understands enough about regulatory toxicology, emergency response, relevant physicochemical properties, hazard and precautionary statements and shipping regulations to provide responders with enough information to respond to an incident. Here, incident means an unexpected release with possible exposure to people, a release into the environment or a fire or possible explosion.

In my world, the word “accident” isn’t used so much anymore. With the advent process hazard analysis (PHA) required by OSHA under Process Safety Management prior to the startup of a process, potential hazards and dangers are anticipated by a group of experienced experts and adjusted for. So, it is getting harder to have an unexpected event. “Accident” is being replaced with the word “incident.”

Toxicology is a specialty concerned with poisons. Regulatory toxicology refers to the field where measurements and models are used to define where a substances belongs in the many layers of applicable regulations. Toxicity is manifested in many ways with many consequences and each way is categorized into levels of severity. There is acute toxicity and there is chronic toxicity. Know the difference. That said, dose and exposure are two different things. Exposure relates to the presence of external toxicants, i.e., ppm in water or micrograms per cubic meter of air. Dose relates to the amount of toxicant entering the body based on the exposure time in the presence of a toxicant and the route of entry.

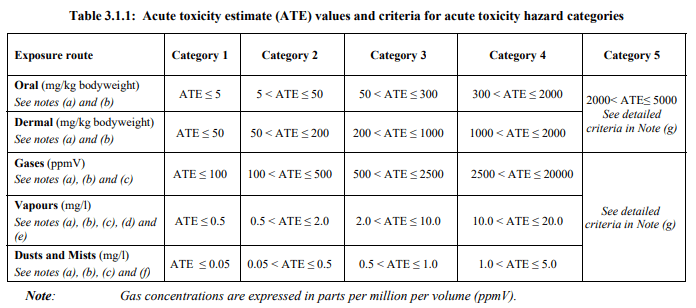

An SDS uses signal words like “Caution”, Warning”, or “Danger”. A particular standard test is needed to narrow down the type and magnitude of the toxicity. The figure below from the GHS shows the thresholds for categorization of Acute Toxicity.

Hazard and precautionary statements are important for an SDS. Rather than having everybody dreaming up their own hazard descriptions and precautions, this has been standardized into agreed upon language. Among other sources, Sigma-Aldrich has a handy list of Hazard Statements and Precautionary Statements available online.

Regulatory toxicology is very much a quantitative science enmeshed with a web of regulations. The EPA for instance does modeling of human health and environmental risks based on quantitative exposure or release inputs. Without toxicological and industrial hygiene testing data, they may fall back on model substances and default, worst case inputs to their models. In reality the certain hazard warnings you see on an SDS may or may not be based on actual measurement. The EPA can require that certain hazard statements be put on a given SDS based on their assessment of risk using models or actual data.

To be clear, hazard information reported on an SDS are considered gospel to emergency responders. Chemists of all stripes should be conversant with Safety Data Sheets and have a look at them the next time a chemical arrives. Your lab or facility should have a central location for SDS documents, paper or electronic.

In the handling and storage of chemicals, some thought should be given as to how a non-chemist would deal with a chemical spill. Is the container labeled with a CAS number or a proper name rather than just a structure? A proper name or CAS # could lead someone to an SDS. Is there an HMIS or other hazard warning label? There are many tens of thousands of substances that are either a clear, colorless or amber liquid or a colorless solid. If not for the sake of emergency responders then for the poor sods in EH&S who will likely have to dispose of the stuff when you are long gone. Storing chemicals, liquids especially, with some kind of secondary containment is always a plus. Keep the number of kilograms of combustibles and flammables in the lab to a minimum. A localized fire is better than a fire that quickly spreads to the clutter on the benchtop or the floor.