As wondrous as our physical and chemical senses are, they are severely constrained in a few fundamental ways. Our vision is limited to our retinal response to a narrow, 1-octave wide band of electromagnetic radiation. As it happens, this band of light can be absorbed non-destructively by or stimulate change in the outer, valence level of inorganic and organic molecules. Electrons can be promoted to higher energy levels and in doing so temporarily store potential energy which can then do work on features at the molecular level. In the retina, this stimulates a polarization wave that propagates along the nervous system.

Owing to the constraints of the optics of the band of light we can sense, we cannot see atoms or molecules with the naked eye. This is because the wavelengths in the narrow range of visible light are larger than objects at the atomic scale. Instead, we perceive matter as a continuous mass of material with no indication of atomic scale structures. No void can be seen between the nucleus and the electrons. For the overwhelming majority of human history, we had no notion of atoms and molecules.

Democritus (ca 460-370 BCE) famously asserted that there exist only atoms and vacuum, everything else is opinion. The link provides more detail. The point is that atoms and vacuum were proposed more than 2000 years ago in Greece. The words of Democritus have survived over time but I’ll hazard a guess that the words were not influential in the rise of modern atomic theory in the 19th and 20th centuries. A good question for another day.

In all chemistry, energy is added to the valence level of a molecule as electronic, rotational, vibrational or translational energy.

Thumbnail Sketch of the Interaction of Light and Matter

Radio waves are a band of long wavelength that can interact with electrically conductive materials. Electromagnetic waves having a wavelength greater than 1 meter are considered to be radio waves. As a radio wave encounters a conductor, the oscillating electric field of the wave causes charge to oscillate in the conductor and at a rate matching the radio wave. Radio waves, whether in electronic devices or in space, are formed by the acceleration of charged particles. Recall that when you cause a charged particle to change it’s direction of motion, e.g., by a magnetic field, it is undergoing an acceleration. It is useful to know that radio waves are non-ionizing.

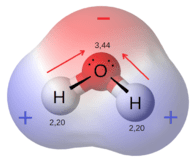

Microwave energy causes dipolar molecules to rotate back and forth by torsion as the waves pass. This rotational energy can be transferred to translational and vibrational energy through collisions, raising the temperature. The molecule does not need fully separated charges like a zwitterion, but molecules may have less than full charge on one side and a less than a full opposite charge on the other side, like water. This is a dipole. Water has a strong dipole and is susceptible to absorbing energy from microwaves.

Infrared radiation causes individual chemical bonds and entire frameworks to vibrate in specific ways. The Wikipedia link for this topic is quite good. When a molecule absorbs heat energy, it is partitioned into a variety of vibrational modes which can bleed off into other energy modes, raising the temperature.

Ultraviolet light is energetic enough to break chemical bonds into a pair of “radicals”- single valence electron species. These radicals are exceedingly reactive over their very short lifetime and may or may not collapse back into the original bond. Instead they can diffuse away and react with features that are not normally reactive, leading to the alteration of other molecules. UV light is very disruptive to biomolecules.

X-rays are more energetic than ultraviolet light and can cause destructive ionization of molecules along their path. They can dislodge inner electrons leaving an inner shell vacancy. An outer shell electron can collapse into the inner vacancy and release energy that can eject a valence level electron, called an Auger electron. This alters the atom by ionization and giving a change in reactivity. X-rays are also produced by the deceleration of electrons against a solid like copper though lighter targets can also produce x-rays.

Gamma radiation originates from atomic nuclei and their energy transitions. They are the highest energy form of electromagnetic radiation and cover a broad range of energies at <0.01 nanometer wavelengths. Many radioactive elements emit only gamma rays as a result of their nuclei being in an unstable state. Some nuclei can emit an alpha or beta particle resulting in an unstable nucleus that will then emit a gamma to relax.

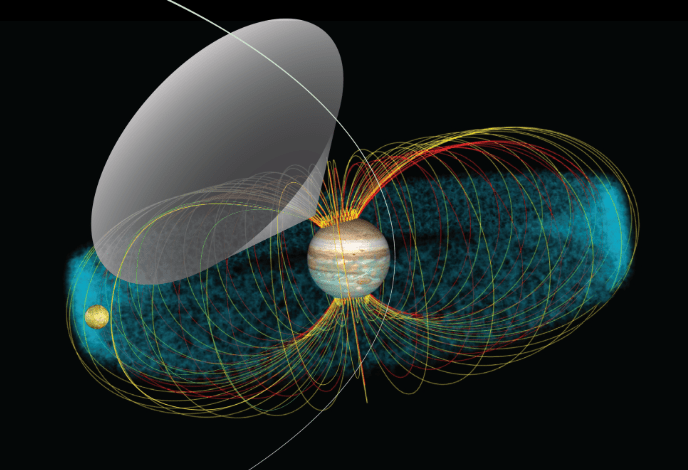

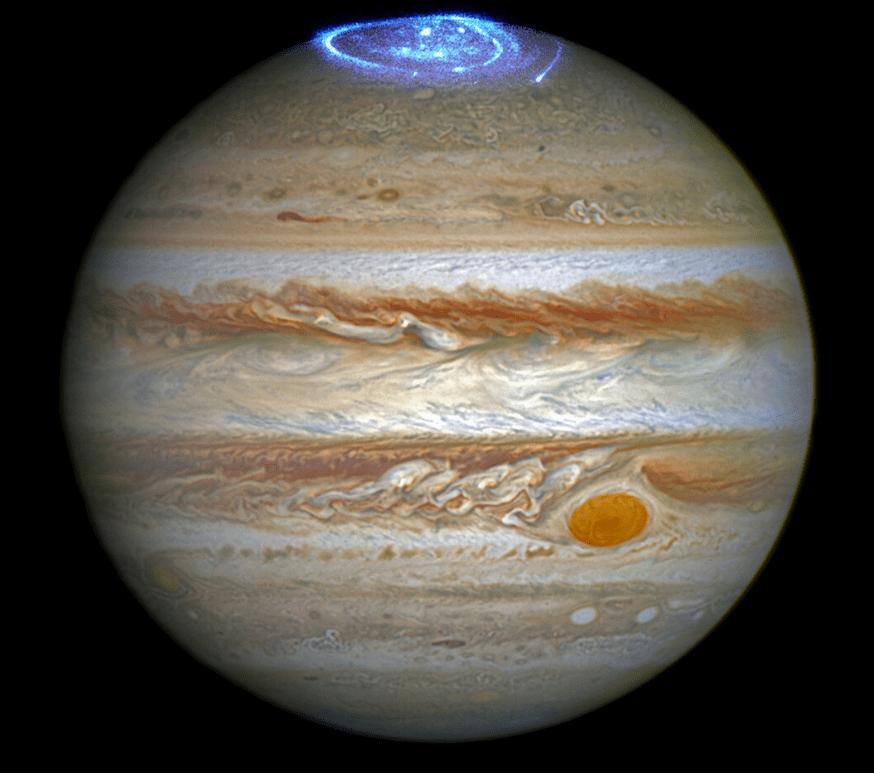

The wavelengths of radio waves are too long and too weak to interact with biomolecules. Some radio waves come from the synchrotron effect where charged particles like electrons will corkscrew around magnetic field lines of a planet and release energy in the form of radio waves. In the case of Jupiter and it’s moon Io, a stream moving charged particles are accelerated by a magnetic field, the particles will emit mainly in the 10 to 40 MHz (decametric) range of radio waves as they spiral around the magnetic field lines into Jupiter. Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io sends charged particles into the planet’s polar regions where the magnetic field lines bunch up. This leaves a visible trace of borealis-like gas that glows. That radiation is emitted in the shape of a conical surface. It is only detectable here when the cone sweeps past earth as Io obits Jupiter.

NASA/GSFC/Jay Friedlander

An atomic nucleus can absorb or emit gamma rays. For instance the gamma emitter Antimony-124 emits a 1.7 MeV gamma that can be absorbed by Beryllium-9 which photodisintegrates into a 24 kiloelectron volt neutron and two stable He-4 nuclei. This nuclear reaction can be used for surveying for beryllium ore deposits by detecting neutron backscatter.

The purpose of this cooks tour of the electromagnetic spectrum is to suggest that visible light band is uniquely suited to interact with matter just enough to induce valence-level chemical changes. The change can be charge separation or an alteration in the composition or shape of a molecule. The changes may be reversible or not.

Ok, done with that.

So, not all electromagnetic radiation plays nicely or at all with any given chemical substance. The narrow visible band of light is uniquely well suited to interact non-destructively, mostly, with living things. Chemistry is about the behavior of the outer, valence level of electrons around and between atoms and molecules.

The retinas in our eyes send signals to the brain continuously that result in a very curious thing- our perception of color registers instead of just a grey scale. Not just the colors of the rainbow, but also more nuanced perceptions like pastels, brown and in their many textures- all with binocular vision!

The constraints on human vision depend on the chemical composition and anatomical structures of the retina as well as the construction of the brain. As the description of the various bands of electromagnetic radiation suggest, there is much to the universe that our senses cannot detect. We do not directly view the radio, microwave, infrared, ultraviolet, x-ray or gamma ray views of the universe.

Our daily understanding of the universe is mostly framed by what we can see with the unique biochemistry and anatomy of the retina. It’s not a bad thing with its limitations, but for an appreciation of the true scope of the universe we would have to find ways to view in the other electromagnetic radiation bands. And, we do. With radio telescopes and satellites that pickup x-ray and UV energy to give images. Now with JWST, we’re peering deeper into the universe as revealed by infrared energy. The longer wavelengths of infrared can pass through clouds of dust particles that previously blocked our view in the optical spectrum.

The structures of the atom and molecules are characterized by the very large fraction of “empty” space they contain. Electrons seem to be point charges with no measurable size. Yet they have mass, spin and the same magnitude of charge but opposite that of the much heavier proton. And, the proton is not even a fundamental particle but a composite particle. It’s like a bag with three hard objects in it.

The universe is wildly different from what our senses present to us. All matter1 is made of mostly empty space. What we see as color doesn’t exist outside of our brains. Our sensation of smell is the same. Cold is not a thing. It is just the absence of heat energy. Finally, our consciousness exists only in our brains. It is a natural phenomenon that is highly confined, self-aware and may be imaged through its electrical activity or F-19 MRI with fluorinated tracers. This wondrous thing is happening on the pale blue dot floating in the vastness of empty space. So far, we can’t find anywhere else in the observable universe where this occurs.

It is good to remember that we search for extraterrestrial intelligence to a large extent with radio telescopes. On earth, the use of radio communication is a very recent thing, tracing back to the beginning of radio in 1886 in the laboratory of Professor Heinrich Rudolf Hertz at the University of Karlsruhe. Hertz would generate a spark and find that another spark would occur separately.

By 1894, Marconi was working on his scheme to produce wireless transmissions over long distances. The wider development of radio transmissions/receiving is well documented, and the reader can find a rabbit hole into its history here.

In order for the discovery of radio transmission to occur, several other things must have been developed first. The discovery of electricity had to precede the development of devices to generate stable sources of electricity on demand and with sufficient power. Then there is the matter of DC vs AC. Some minimal awareness of Coulombs, voltage, current, electromagnetism, conductors and insulators, and wire manufacturing is necessary to build induction coils for spark generation.

James Clerk Maxwell had developed a series of equations before the discovery of wireless transmission by Hertz. Hertz was very familiar with the work of Maxwell from his PhD studies and post doc under Kirchhoff and Helmholtz. Hertz was well prepared in regard to the theory of electromagnetism and was asking the right questions that guided his experimental work.

Radio transmission came to be after a period of study and experimentation by people like Marconi, Tesla and many others who had curiosity, resources and drive to advance the technology. As the field of electronics grew, so did the field of radio transmission. It’s not enough to build a transmitter- a receiver was required as well. Transmitter power and receiver sensitivity were the pragmatics of the day.

This was how we did it on earth. It was facilitated by the combined use of our brains, limbs, opposable thumbs and grasping hands. Also, an interest in novelty and ingenuity during this period of the industrial revolution was popular. While people who lived 10,000 years ago could certainly have pulled it off as well as we did, the knowledge base necessary for even dreaming up the concepts was not present and wouldn’t be for thousands of years. The material science, mathematics, understanding of physics, and maybe even cultures that prized curiosity and invention were not yet in place.

In order for extraterrestrials reaching out to send radio signals that Earthlings could detect, they would have to develop enough technology to broadcast (and receive) powerful radio transmissions. If you consider every single mechanical and electrical component necessary for this, each will have had to result from a long line of previous developmental work. Materials of construction like electrical conductors could only arise from the previous development of mining, smelting and refining as a prelude to conductor fabrication to produce a way of moving electrical current around.

Radio transmission requires electrical power generation and at least some distribution. None of this could have been in place without the necessary materials of construction, mechanical and electrical components already in place. Most of the materials would have to have been mined and smelted previously. Electrical power generators need to be energized by something else to provide electricity. On earth we use coal or natural gas to produce steam that drives generator turbines to make electricity. Also, there is nuclear and hydroelectric power. ETs would face a similar problem for the generation of electrical power.

If you follow the timeline leading to every single component of an operating radio transmitter, you’ll see that it requires the application of other technologies and materials. It seems as though a radio transmission from extraterrestrial home planets need something like an industrial base to get started.

What if there were intelligent extraterrestrials who were not anatomically suited to constructing radio transmitters for their own Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence or just for local use? Perhaps they are +very intelligent but not far along enough yet to have developed radio. Or, what if they were just disinterested in radio? What if they used radio for a short window in time and have been using something else not detectable from earth, like what we do with optical cable? The point is that we would never hear them by radio, yet they would be there.

Surely there is a non-zero probability of this happening. This dearth of signal may be so prevalent that we will conclude that we are alone in our local region of space. Perhaps funding will be cut and we’ll quit looking. We can take that finding to fuel our sadness of being alone in the cosmos. Or we could use it to appreciate just how unique life is and take better care of ourselves.

Instead of buying into Elon Musk’s vision of colonizing Mars and somehow terraforming it, why don’t we terraform Earth back into a place where the biosphere is more stable and pollution is pushed back to some lower level? A utopian vision for sure, but it also has a non-zero probability of happening.

1. Not including dark matter, if it really exists. I remain skeptical.