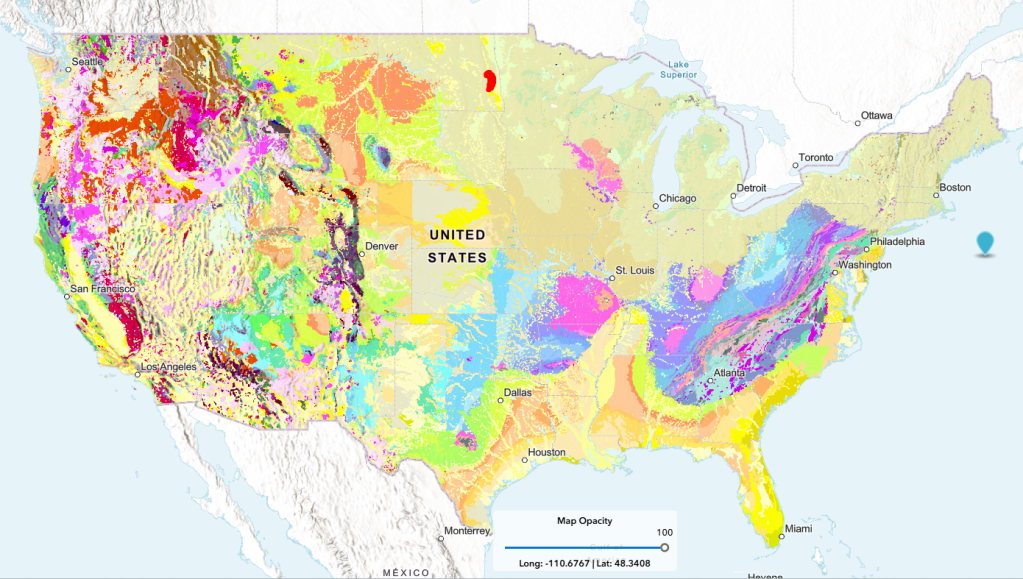

The United States Geological Survey, USGS, has released an interactive geological map that includes 4 layers of stratigraphy- Surface, Quaternary, Pre-Quaternary and Precambrian layers with color coded rock units displayed. A click of the cursor on the map reveals the type of rock unit chosen. The website is called The Cooperative National Geologic Map.

Category Archives: Science Education

The How and Why of Science

Preamble

There are more than a few definitions of science out there. Every scientist you ask will give their favorite variation on a common theme. The whole business of science is built ideally around the concept of the scientific method. One of the better broad definitions of the scientific method is this-

The scientific method – the method wherein inquiry regards itself as fallible and purposely tests itself and criticizes, corrects, and improves itself.

Source: The Scientific Method, Wikipedia.

Wikipedia as a Source of Authoritative Information

First, a homily on Wikipedia as a resource. It’s been my observation that in areas that I am familiar with, i.e., chemistry, aviation, the history of science and a few others, the content I’ve encountered comports well with my general knowledge. The more links and references, the better. And, more often than not, the links actually reflect the content that referenced it. What’s more, Wikipedia encourages input and corrections by the broader community and if you go into edit mode, you can see the list of edits over time. I’ve contributed to a few edits myself. Are there errors or just simple BS in Wikipedia? Well, of course. It’s been said that a camel is a horse designed by committee. While Wikipedia may reveal some of this camel design in places, basically most everything we read or hear is subject to this shortcoming. The freedom to edit a Wikipedia entry is a type of “peer review” but the qualifications of the peers is unknown. Believe me, in science publishing, anonymous peer reviewing is populated with more than a few sanctimonious jerks whose motivations may not be pure.

I’ve spent my career diving into the primary chemical literature via Chemical Abstracts. Primary literature is crucial, but it is usually very narrow in scope and often subject to later revision. This is why review articles, books and monographs are so important. Someone has combed through the primary literature and brought together some structure in an area of study. Wikipedia has become a third tier of scientific information and access for anyone. While it seems quite accurate, we should always be using our best judgement as we read the content. Do the links support the statements? Are there enough links, etc.?

A great deal has been written about the scientific method by those more capable than I so I won’t attempt to blather through it. Instead, I will share an example of how asking a very basic question led me to a treasure trove of information expanding my understanding of the universe.

Back to the definition of science. From a Google search of “Science”: ”Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence.” I’ve quoted it because I can’t improve on it.

Science is frequently regarded with excessive reverence, suggesting that it is solely the realm of “proper scientists” and embodies the ultimate truth. However, in reality, it is open to anyone armed with curiosity and resolve. Curiosity drives inquiry, but it is also enhanced by a prepared mind. Some questions illuminate, while others can deceive. A well-posed question can propel one towards the heart of a matter. A ready mind can recognize false trails early on and steer clear of them.

How or Why?

I favor “how” questions over “why” questions because they foster a more mechanistic inquiry into nature and adhere to established physical principles. “Why” questions often carry philosophical or religious connotations and can be laden with presupposed motives or assumptions. This doesn’t render “why” questions invalid; however, they may veer away from the realm of observable natural phenomena, the foundation of scientific inquiry. Asking “How did Stella move the lamp?” may differ from “Why did Stella move the lamp?”. The interchangeable use of ‘why’ and ‘how’ in everyday language can result in imprecise thinking and sloppy conclusions.

Obviously both how and why questions are useful is answering a question. Judicious use of ‘how’ and ‘why’ can lead to more focused thinking about either a mechanistic or motivational question. ‘How’ gets to physical causality whereas ‘why’ often seeks mechanist details but may also leave room for psychological motivation. Either entry into a question is valid depending on what a person wants to know: Physics or psychology.

Sharply pointed scientific inquiry requires the meticulous use of language to convey exact meanings. This scrupulous attention to language demands a precise vocabulary that narrows the scope of interpretation. While this may seem tedious, the benefit lies in getting quickly to the heart of a question. Similarly, lawyers have developed their specialized legalese for this very reason.

Being more precise in one’s use of language is very useful if you’re plagued with complex situations, incomplete information or the need to focus on a mechanistic pathway. ‘How‘ thinking helps with this.

>>> The best questions lead more directly to the best answers. <<<

As one accumulates a greater vocabulary over time, the ability to apply nuances into your thinking and communication increases as well since even synonyms can differ a bit in their meaning. As you spend more time in scientific pursuits, you start to realize the value of having good questions to ask. In fact, the skill with which you formulate questions can drive your research further into the unknown, which is where everyone wants to go.

Lamentations on Science Infotainment Rev 2.

Note: This post appeared May 15, 2007, as “Infotainment, Chemistry, and Apostasy“. I have pulled it up through the mists of time for another go and with a few edits.

In the normal course of things I used to give school chemistry talks or demonstrations a couple of times per year and until recently, I had been giving star talks at a local observatory more frequently. The demographic is typically K-12, with most of the audience being grades 3-8. From my grad student days through my time in the saddle as a prof, I was deeply committed to spreading the gospel of orbitals, electronegativity, and the periodic table. I was convinced that it was important for everyone to have an appreciation of the chemical sciences. I was a purist who knew in his bones that if only more people were “scientific”, if greater numbers of citizens had a more mechanistic understanding of the intermeshing great world systems, the world could somehow be a better place.

In regard to this ideology that everyone should know something about chemistry, I now fear that I am apostate. I’m a former believer. What has changed is an updated viewpoint based on experience.

Let me make clear what science is not. It is not a massive ivory tower that is jealously guarded ajd intended to be impenetrable by mortal folk. Big science requires big funding and organizational support, so big administrative structure forms around it. At its core, science is concerned with learning how the universe works by observation, constructing a good first guess (theory) on what is happening, measurement (conducting quantitative experiments), analysis (quantitative thinking), documentation and communication. The common understanding is that a scientist is someone who has been educated and employed to do these activities. However, anyone who conducts a study of how some phenomenon happens is doing science whether for pay or not.

What science has learned is that the universe is quite mechanistic in how it works. So much so that it can be described by or represented with math. At the fundamental level of ions, atoms and molecules, constraints exist on how systems can interact and how energy is transferred around. At the nanometer-scale, quantum mechanical theory has provided structure to the submicroscopic universe.

Chemical knowledge is highly “vertical” in its structure. Students take foundational coursework as a prerequisite for higher level classes. Many of the deeper insights require a good bit of background, so we start at the conceptual trailhead and work our way into the forest. But in our effort to reach out to the public, or in our effort to protect a student’s self-esteem, we compress the vertical structure into a kind of conceptual pancake. True learning, the kind that changes your approach to life, requires Struggle.

What I found in my public outreach talks on science- chemistry or astronomy- was the public’s expectation of entertainment. Some call it “Infotainment”. I am all in favor of presentations that are compelling, entertaining, and informative. But in our haste to avoid boredom, we may oversimplify or skip fascinating phenomena altogether. After all, we want people to walk out the door afterwards wanting more. We want science to be accessible to everyone, but without all the study.

But I would argue that this is the wrong approach to science. Yes, we want to answer questions. But the better trick is to pose good questions. The best questions lead to the best answers. People (or students) should walk out the door afterwards scratching their heads with more questions. Science properly introduced, should cause people to start their own journey of discovery. Ideally, we want to jump-start students to follow their curiosity and integrate concepts into their thinking, not just compile a larger collection of fun facts.

But here is the rub. A lot of folks just aren’t very curious, generally. As they sit there in the audience, the presentation washes over them like some episode of “Friends”. I suspect that a lack of interest in science is often just part of a larger lack of interest in novelty. It is the lack of willingness to struggle with difficult concepts. But that is OK. Not everyone has to be interested in science.

Am I against public outreach efforts in science? Absolutely not. But the expectation that everyone will respond positively to the wonders of the universe is faulty. It is an unrealistic expectation on the 80 % [a guess] of other students who have no interest in it. I’m always anxious to help those who are interested. It’s critical that students interested in science find a mentor or access to opportunity. But, please God, spare me from that bus load of 7th graders on a field trip.

What we need more than flashier PowerPoint presentations or a more compelling software experience is lab experience. Students need the opportunity to use their hands beyond mere tapping on keyboards- they need to fabricate or synthesize. You know, build or measure stuff.

It is getting more difficult for kids to go into the garage and build things or tear things apart. Electronic devices across the board are increasingly single component microelectronics. It is ever harder to tear apart some kind of widget and figure out how it works. When you manage to crack open the case what you find is some kind of green circuit board festooned with tiny components.

And speaking of electronics or electricity, I find it odd that in a time when electric devices have long been everywhere in our lives, that so FEW people know even the first thing about electricity. I instruct an electrostatic safety class in industry and have discovered that so very, very few people have been exposed to the basics of electricity by graduation. I spend most of the course time covering elementary electrostatic concepts along with the fire triangle so the adult learners can hopefully recognize novel situations where static electric discharge can be expected. Of course, we engineer away electrostatic discharge hazards to the greatest extent possible. But if there is a hole, somebody will step in it. It’s best they recognize it before stepping into it.

The widespread educational emphasis on information technology rather than mechanical skills ignores the fact that most learners still need to handle things. There is a big, big world beyond the screen. A person will take advantage of their mechanical skills throughout their life, not just at work. Hands on experience is invaluable, in this case with electricity. Computer skills can almost always be acquired quickly. But understanding mechanical, electrical and chemical systems need hands-on experience.

Hedging Language Frequency Down in Papers Published in the Journal “Science”

Historically, scientific papers have been not where loud, confident proclamations are made about academic research results. The trend has been a sort of unpretentious modesty to avoid overconfidence and exaggerated claims. A sort of snobismus. Instead, conclusions from research results tend to be more guarded in the interpretation of data. An article in the Scienceinsider section of the AAAS journal Science published 28 July, 2023, has reported that of 2600 papers published in Science between 1997 and 2021, there was a drop of about 40 % in the use of hedging language. Researchers in the study scanned for about 50 terms including “might,” “probably,” “could,” “approximately,” “appear to” and “seem.” They found that these hedging words dropped from 115.8 per 10,0000 to 67.42 per 10,000.

Analyses of other scientific journals and a 2022 paper that examined nearly the same group of papers from Science have found growing use of a positive, promotional tone—expressed with superlatives such as “groundbreaking” and “unprecedented”—which may lead to exaggerated claims.

Source: Science, 28 JUL 2023 BY JEFFREY BRAINARD.

The authors suggested that researchers are increasingly unwilling to undersell their work and instead, are using more hyperbolic language such as “groundbreaking” and “unprecedented.”

In an earlier study by C.H. Vinkers et al., published in BMJ, 2015, finished his paper with the following paragraph-

“Currently, most research findings could be false or exaggerated, and research resources are often wasted. Overestimation of research findings directly impairs the ability of science to find true effects and leads to an unnecessary focus on research marketability. This is supported by a recent finding that superlatives are commonly used in news coverage of both approved and non-approved cancer drugs. The consequences of this exaggeration are worrisome since it makes research a survival of the fittest: the person who is best able to sell their results might be the most successful. It is time for a new academic culture that rewards quality over quantity and stimulates researchers to revere nuance and objectivity. Despite the steady increase of superlatives in science, this finding should not detract us from the fact we need bright, unique, innovative, creative, and excellent scientists.”

If you sit through a week of presentation sessions at an American Chemical Society national meeting or walk through a poster session, you’ll see a mix of enthusiastic young chemists standing next to their posters and you’ll sit through talks by more established researchers anxious to emphasize the importance of their work. Giving a talk or a poster at a meeting is inherently a promotional activity. It is getting the word out about you and your work in a particular area in front the scientific community and possibly some influential people. It also is something to add to your resume.

Self-promotion by scientific publishing and participation in meetings, called “ballyhoo” in the movie business, is a great way to expose yourself to greater and more frequent opportunity. Make no mistake, the quality and frequency of publications is a very important metric of your accomplishments and potential. This is a sad reality for some and a fortunate reality for a few, but it is reality.

It is hard to draw much from the above research on the hedging frequency as a metric of … what, the unseemly disappearance of proper modesty? The competitive environment of “big academic science” for funds and exposure to impress colleagues and the rank and tenure committee is inevitable. It has been like that for a very long time, but perhaps hidden under the veil of snobbery.

You never know who you might meet at these venues for academic ballyhoo. I once loaned my laser pointer to Al Cotton (who kept it!) and I met Glenn Seaborg at a poster session at the Disney Hotel in Anaheim, CA. I had too many gin & tonics before I spoke with Seaborg and I’m sure that it showed. At a symposium at Purdue University in honor of H.C. Brown (in attendance), I got to see two prominent scientists get into a rather strong “discussion” during a question-and-answer period about who discovered what first. Professor Suzuki (Suzuki coupling) from Japan said something that got under the skin of prof Negishi (Negishi coupling) from Purdue, so they began with point-counter-point exchange (a type of coupling?) which soon accelerated into an argument. As it got more contentious, they switched to speaking Japanese and continued their argument. After a short time, they realized it was best to just sit down as they were providing a “Clash of the Titans” spectacle. This is not a criticism, just an amusing anecdote. Guys like this should battle it out in public more often.

Self-promotion using exuberant language isn’t inherently bad. It is likely that others have already judged you based on far smaller misperceptions. If someone wants to embarrass themselves, let ’em.

Hossenfelder and Poliakoff

One can learn interesting but off-topic things along the way to a particular subject of research. Below is a compilation of interesting things.

We are all aware of the games Russia is playing with the interruption of natural gas supplies to Europe. A noteworthy consequence of this applies to the refining of petroleum. Evidently, refineries use natural gas in the refining process, likely as a fuel for heating process equipment. A shortage of natural gas may/will have an adverse effect on the ability of European refineries to produce fuels from crude oil.

There is a German theoretical physicist named Sabine Hossenfelder who has been producing short videos for YouTube. I’ve seen a few and they are quite good. She doesn’t pander to the lowest common denominator. Instead she speaks like a theoretical physicist talking to intelligent non-specialists and does a bang-up job of it. She gives a thoughtful and skeptical analysis of current topics in theoretical physics. She always gets back to basic concepts and what is possible for science to understand. She has moved on to subjects of popular interest as well.

And speaking of videos on YouTube, I’ve taken a shine to a channel called Periodic Videos. The presenter is professor Sir Martyn Poliakoff of the University of Nottingham. It may take a few moments to overcome the shock of his wild white hair. Poliakoff has produced a great many short videos over the years specializing in the chemical elements. A good one I viewed recently was about burning magnesium in a nitrogen atmosphere. Yes, it can happen and it will produce magnesium nitride. Contact it with water and you get ammonia. It is easy to think that nitrogen is an all around inert gas and for the most part it is. Lithium metal springs to mind when inert atmosphere questions arise. Better use argon.

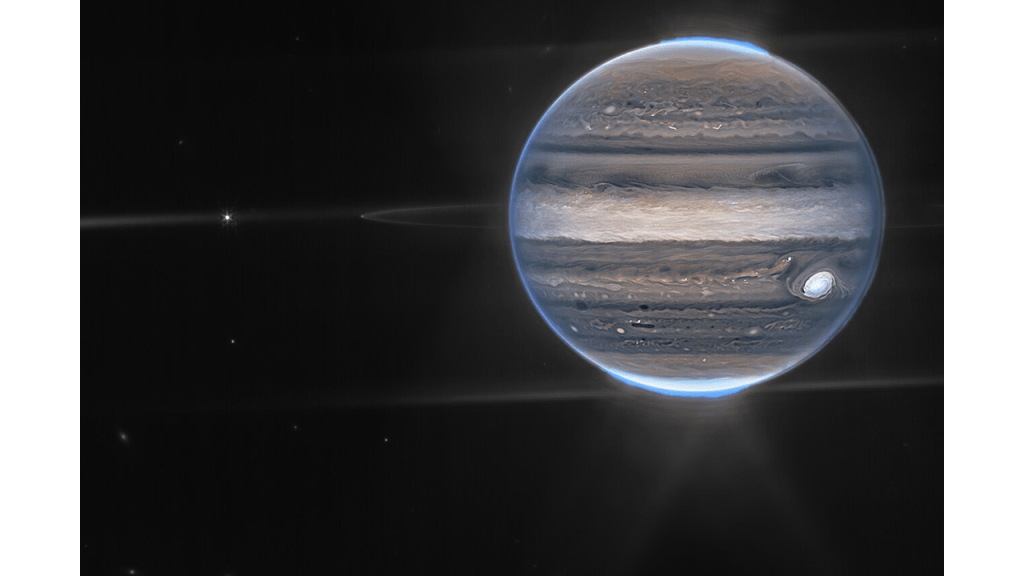

JWST Jupiter Image in False Color

A spectacular image of Jupiter, its rings and several moons from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was recently released.

When looking at JWST images it is useful to remember that the camera is sensitive in the range of 0.6 (orange) to 5 (mid-infrared) microns. The human eye is sensitive to the range of 0.38 (violet) to 0.75 microns (red)- remember ROYGBIV? Image colors with a wavelength shorter than orange, 0.6 micron, green, blue and violet, are therefore a false color representation. In fact, all of the colors and intensities are chosen with both Hubble and JWST images. NASA is up front about this and an explanation can be found here.

A pet peeve of mine with the recent first radio image of a black hole (Sgr A*) has been that the colors represented are necessarily false, but left unexplained. This is well known to astronomers and other pointy-headed space weenies but not to the flat-headed public. The object may well be orangish from some nearer distance, but the reconstructed radio image we see is processed by software and intentionally given a visual color chosen by some person. This is fine, but a sentence or two about colored radio images is a lost opportunity for greater insight into instrumentation and the properties of light.

Alright, I’m sorry- I exaggerate. The public isn’t flat-headed. Okay? Is that better?

Earth Day on the Pale Blue Dot

This Earth Day of April 22, 2022, is a good time to stop and reflect a moment on our home in the universe. We live on a gleaming blue and white wet rock hurtling around a yellow star in a cosmos so vast that it is well beyond our ability to comprehend. On February 14, 1990, a photo looking back at Earth was taken from a distance of 4 billion miles by the space probe Voyager 1 on its way out of the solar system. This photo features a tiny, pixel-sized, blue dot. Our lonely home world.

So far, this decade of the 2020’s has begun with global contagion and a growing standoff by nuclear powers over culture and real estate. Many are saying that the conflict will lead to famine in Africa and economic chaos elsewhere. How it unfolds is the question on everyone’s mind. If there was ever a time for us to take a pause to look at the big picture, that time is now. We could all use a bit of humility from time to time.

Someone once joked that the international unit of humility should be called the “Sagan.” Carl Sagan the astronomer was a gifted and popular spokesman for astronomy and space science in a time of great discovery and space exploration in the latter 1900’s. Carl Sagan the writer is said to have published more than 600 scientific papers and 20 books for lay audiences. What’s more, in addition to co-writing and narrating a popular TV series, he wrote a piece of science fiction, Contact, that was turned into a popular movie.

Sagan wrote the following-

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

— Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot, 1994

Copyright © 1994 by Carl Sagan, Copyright © 2006 by Democritus Properties, LLC.

Flame and Ash again

Here is a link to one of my better posts. It is titled Flame and Ash. There is some interesting history in the development of illumination. It sounds trivial, trying to get good illumination from a flame, but it took a while.

For Students. Thoughts on Chemical Process Scale-Up.

Chemical process scale-up is a product development activity where a chemical or physical transformation is transferred from the laboratory to another location where larger equipment is used to run the operation at a larger scale. That is, the chemistry advances to bigger pots and pans, commonly of metal construction and with non-scientists running the process. A common sequence of development for a fine chemical batch operation in a suitably equipped organization might go as follows: Lab, kilo lab, pilot plant, production scale. This is an idealized sequence that depends on the product and value.

Scale-up is where an optimized and validated chemical experimental procedure is taken out of the hands of R&D chemists and placed in the care of people who may adapt it to the specialized needs of large scale processing. There the scale-up folks may scale it up unchanged or more likely apply numerous tweaks to increase the space yield (kg product per liter of reaction mass), minimize the process time, minimize side products, and assure that the process will produce product on spec the first time with a maximum profit margin.

The path to full-scale processing depends on management policy as well. A highly risk-averse organization may make many runs at modest scale to assure quality and yield. Other organizations may allow the jump from lab bench to 50, 200, or more gallons, depending on safety and economic risk.

Process scale-up outside of the pharmaceutical industry is not a very standardized activity that is seamlessly transferable from one organization to another. Unit operations like heating, distillation, filtration, etc., are substantially the same everywhere. What differs is administration of this activity and the details of construction. Organizations have unique training programs, SOP’s, work instructions, and configurations of the physical plant. Even dead common equipment like a jacketed reactor will be plumbed into the plant and supplied with unique process controls, safety systems and heating/cooling capacity. A key element of scale-up is adjusting the process conditions to fit the constraints of the production equipment. Another element is to run just a few batches at full scale rather than many smaller scale reactions. Generally it costs only slightly more in manpower to run one large batch than a smaller batch, but will give a smaller cost per kilogram.

Every organization has a unique collection of equipment, utilities, product and process history, permits, market presence, and most critically, people. An organization is limited in a significant way by the abilities and experiences of the staff who can use the process equipment in a safe and profitable manner. Rest assured that every chemist, every R&D group, and every plant manager will have a bag of tricks they will turn to first to tackle a problem. Particular reagents, reaction parameters, solvents, or handling and analytical techniques will find favor for any group of workers. Some are fine examples of professional practice and are usually protected under trade secrecy. Other techniques may reveal themselves to be anecdotal and unfounded in reality. “It’s the way we’ve always done it” is a confounding attitude that may take firm hold of an organization. Be wary of anecdotal information. Define metrics and collect data.

Chemical plants perform particular chemical transformations or handle certain materials as the result of a business decision. A multi-purpose plant will have an equipment list that includes pots and pans of a variety of functions and sizes and be of general utility. The narrower the product list, the narrower the need for diverse equipment. A plant dedicated to just one or a few products will have a bare minimum of the most cost effective equipment for the process.

Scale-up is a challenging and very interesting activity that chemistry students rarely hear about in college. And there is little reason they should. While there is usually room in graduation requirements with the ACS standardized chemistry curriculum, industrial expertise among chemistry faculty is rare. A student’s academic years in chemistry are about the fundamentals of the 5 domains of the chemical sciences: Physical, inorganic, organic, analytical, and biochemistry. A chemistry degree is a credential stating that the holder is broadly educated in the field and is hopefully qualified to hold an entry level position in an organization. A business minor would be a good thing.

The business of running reactions at a larger scale puts the chemist in contact with the engineering profession and with the chemical supply chain universe. Scale-up activity involves the execution of reaction chemistry in larger scale equipment, greater energy inputs/outputs, and the application of engineering expertise. Working with chemical engineers is a fascinating experience. Pay close attention to them.

Who do you call if you want 5 kg or 5 metric tons of a starting material? Companies will have supply chain managers who will search for the chemicals with the specifications you define. Scale-up chemists may be involved in sourcing to some extent. Foremost, raw material specifications must be nailed down. Helpful would be some idea of the sensitivity of a process to impurities in the raw material. You can’t just wave your hand and specify 99.9 % purity. Wouldn’t that be nice. There is such a thing as excess purity and you’ll pay a premium for it. For the best price you have to determine what is the lowest purity that is tolerable. If it is only solvent residue, that may be simpler. But if there are side products or other contaminants you must decide whether or not they will be carried along in your process. Once you pick a supplier, you may be stuck with them for a very long time.

Finally, remember that the most important reaction in all of chemistry is the one where you turn chemicals into money. That is always the imperative.

Reactive Hazards Seminar

One of the safety seminars I teach is on the general topic of reactive hazards. There is a bit of a challenge to this because the idea is to cultivate informed caution rather than allow broadband fear to rule. It is challenging because my class is generally populated with non-chemist plant operators or other support staff. Out in the world the word “chemical” is generally taken to be an epithet and indicative of some malign influence. We who work with chemicals are in a position to bear witness to the reality of chemistry in our lives and to speak calmly and reasonably about it, without crass cheerleading.

Here is how I look at this. There are hazards and there are dangers. A hazard is something that can cause harm if it was to be fully expressed by way of physical contact with people or certain objects, unbounded access to an ignition source, exposure to air, etc. A critical feature of the hazard definition is that there are layers of protection preventing undesired contact. Hazards can be contained. A contained hazard is safer to be around than an uncontained hazard.

An uncontained hazard is that which can cause harm without the interference of effective layers of protection. A hungry tiger in a cage is hazardous in that there is the potential for trouble if the cage is breached. Being openly exposed to that tiger is what I’ll call dangerous.

Likewise, a stable chemical in a bottle has a physical layer of protection around it. A policy on the use of that bottled chemical constitutes a concentric administrative layer of protection. The bottle sitting in a proper cabinet within a room with limited access has more layers of protection. The policy of selling that chemical only to qualified buyers is a further layer of protection.

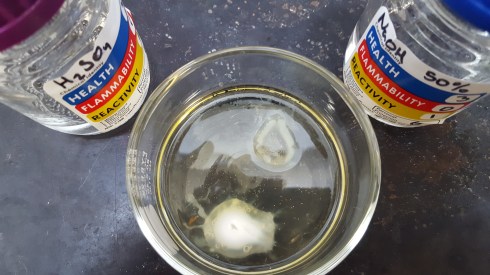

Egg white to which has been added several drops of conc H2SO4 (bottom) and 50 % caustic (top). Two minutes have elapsed. The point of this demo is to show what might happed to a cornea on contact with these reagents. The clouding is irreversible. People remember demonstrations.

It is possible to work around contained hazards safely and most of us do this outside of work without giving it much thought. Hazardous energy is exploited by most of us in the form of moving automobiles, spinning jet turbines, rotating machinery of all kinds, compressed gases and springs, and flammable liquids. Safe operation around these hazards is crucial to the conduct of civilization right down to our daily lives.

It is very easy for experts to frighten the daylights out of people by an unfortunate choice of words or simply dwelling on the hazardous downside too much. Users of technology should always be versed in the good and bad elements as a matter of course.

Risk can be defined as probability times consequence. So, to reduce risk one can reduce probability, diminish undesired consequences, or both. This is the purpose of LOPA, or Layers of Protection Analysis. LOPA can provide a quantitative basis for safety policy. The video below will explain.

Designing for tolerable risk is something that all of us in industry must come to grips with.